20 common misconceptions about US history

Debunking the myths

Delve into the history of the United States and you’ll find a plethora of extraordinary events and stories, from George Washington crossing the Delaware River to Abraham Lincoln freeing the slaves and Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon. When you look a little closer, however, some of the best-known stories fail to ring true.

Click through this gallery to discover the most common misconceptions about the history of the United States...

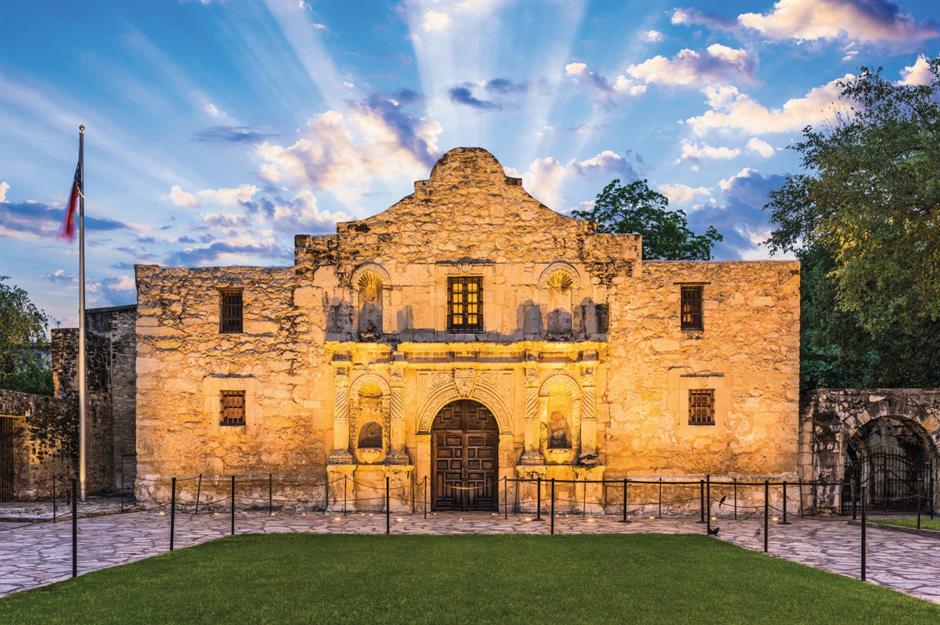

Myth 1: The Alamo was fought for the future of the US

The defence of the Alamo in 1836 was a catastrophe. The ragtag force of around 200 Texans holding out in the mission station-turned-fort near modern-day San Antonio was overrun, and most of them were killed. But the defeat holds a special place in American folklore – a heroic 13-day stand against a far larger Mexican army ending with the ultimate sacrifice in the name of Texas and the US. When the Texans got their revenge at the battle of San Jacinto a month later, "Remember the Alamo!" became a war cry.

Myth 1: The Alamo was fought for the future of the US

The Alamo’s importance to the wider country, however, has been exaggerated. At the time, Texas was not a part of the US but a Mexican territory that had erupted in revolution the previous year. Texans were not protecting a corner of their nation, but fighting – in part – to keep slavery after Mexico had abolished it in 1829. Then, when they defeated the Mexicans, Texas initially declared independence rather than joining the US. It remained a republic for a decade before it became a US state.

Myth 2: Betsy Ross designed the Stars and Stripes flag

In 1870, William Canby presented his paper, The History of the Flag of the United States, in a speech to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, in which he claimed that a Philadelphia seamstress named Betsy Ross made the first Stars and Stripes in 1776, early in the Revolutionary War. Ross had been approached by none other than George Washington for the task, and she quickly refined the design by suggesting using five-pointed stars instead of Washington’s preferred six. A year later, the Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the nation’s flag.

Myth 2: Betsy Ross designed the Stars and Stripes flag

Canby was Betsy Ross’s grandson, and he presented his account shortly after the American Civil War, a time of heightened patriotism when many Americans were looking back to the founding of the US a century before. Historians have found no evidence whatsoever to back up Canby's claim that Ross made the first flag – a more likely contender could be Francis Hopkinson, one of the Founding Fathers – but it caught on anyway, and Ross still holds a special place in the American imagination.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

Myth 3: The Civil War was not fought over slavery

To this day, the legacy of the American Civil War, fought between 1861 and 1865, remains a divisive issue. Fierce debates have raged across the US over the future of statues depicting Confederate leaders and soldiers, and many have been removed. The war is broadly viewed as a fight between the pro-slavery Confederacy and anti-slavery Union, but there have been countless claims that the primary motivation for the Confederacy was not in fact slavery, but states’ rights. Many historians have demonstrated repeatedly that this is not true.

Myth 3: The Civil War was not fought over slavery

Documents announcing the secessions of southern states clearly stated that the need to protect slavery was paramount, given that the economy of the South depended on free labour. The Confederate vice-president, Alexander Stephens, declared in 1861 that the cornerstone of their new government rested “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man, that slavery – subordination to the superior race – is his natural and normal condition”. That is not to say the North solely fought to end slavery, either. At the outset, the bigger goal was to preserve the union; only as the war progressed did abolition become enmeshed with ultimate victory.

Myth 4: Christopher Columbus discovered America

Even if you ignore the issue of whether the Americas could be 'discovered' at all, since they were inhabited by Indigenous populations long before Europeans arrived, Christopher Columbus’s reputation in the US is tricky to justify. It's undeniable that the four voyages the Italian explorer made across the Atlantic Ocean did indeed herald the start of the settlement, conquest and colonisation of the so-called New World, and generations of Americans have honoured his accomplishments with an annual holiday.

Myth 4: Christopher Columbus discovered America

The first problem with his reputation is chronological: it is thought that Norse explorer Leif Erikson landed on continental North America around the turn of the millennium, some 500 years before Columbus. The second is geographical: Columbus travelled around a number of islands in the Caribbean – the Bahamas, Cuba and Hispaniola – and later landed on parts of South and Central America. But he never saw land that would become the US. He also maintained until he died that he'd actually discovered a new route to the East Indies, which was why the native population were known as 'Indians', a term that stuck throughout European colonisation.

Myth 5: Walt Disney was cryogenically frozen

Have you heard how the frozen body of Walt Disney is lying hidden underneath Disneyland's Pirates of the Caribbean ride, which conveniently opened just a few months after his death in 1966? Or perhaps you've heard that just his head was frozen? An extremely persistent myth holds that, after dying from lung cancer at the age of 65, the father of Mickey Mouse ordered his body to be placed in a special machine and kept in ice until scientists developed the technology required to revive him.

Myth 5: Walt Disney was cryogenically frozen

Certainly, Disney had the money and the fascination with technology needed to pursue such an innovative afterlife. But that's as far as the story gets. The truth is disappointingly mundane: records show he was cremated, and his ashes interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in California. In 1972, Disney's daughter Diane poured further cold water on the rumour, saying that she doubted her father had even heard of cryonics. Nevertheless it endures, and the release of Disney smash hit Frozen sparked an even more outlandish rumour that the film had been made to push Walt Disney's non-existent cryogenic scheme off the top of search engine results pages.

Myth 6: The Gettysburg Address was the main speech that day

"The world will little note nor long remember what we say here," said President Abraham Lincoln during a short speech on 19 November 1863, to consecrate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Four months earlier, the North had won the bloodiest engagement of the Civil War, resulting in around 50,000 casualties and turning the tide of the war. While Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address went down as one of history’s great speeches, it was not even scheduled as the primary speech of that day.

Myth 6: The Gettysburg Address was the main speech that day

Edward Everett, a statesman often hailed as the finest orator of his era, spoke, without notes, for two hours on wars throughout the centuries. Compare that to Lincoln’s 271-word speech, which lasted a couple of minutes. “In the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates the battles of Gettysburg,” Everett concluded, to much acclaim. Yet when the president’s "few appropriate remarks" were printed in the newspapers, the power of his words was instantly celebrated.

Myth 7: The big crack in the Liberty Bell is why it stopped being used

As a working bell, the iconic Liberty Bell was disappointing to say the least. Commissioned in 1751 by the Pennsylvania Assembly to hang in the new State House in Philadelphia, it cracked on its first test ring and had to be recast twice. There’s a legend that it cracked when tolled by over-enthusiastic Patriots to mark the Declaration of Independence, and it would crack multiple times more before being forced into silence.

Myth 7: The big crack in the Liberty Bell is why it isn’t used anymore

The Liberty Bell – which picked up its nickname from abolitionists in the 19th century – last rang out clearly to commemorate the birthday of George Washington in 1846. It now stands as an American landmark, with its distinctive crack for all to see. But that was not the fatal fissure: it’s actually from an attempted repair job in the 1840s, evident by the drill marks. Instead, there is another hairline crack running from the top of the bell (ironically running though the word ‘Liberty’) that really did the damage and prevented it from being used again.

Myth 8: Paul Revere made his ride calling, "The British are coming!"

An enduring story from the Revolutionary War is the 'midnight ride' of Paul Revere. On the night of 18 April 1775, the silversmith and avowed revolutionary galloped from Boston to Lexington in order to warn the Massachusetts militias that enemy forces were on the way, supposedly with the cry "The British are coming!" While he certainly was an important messenger that night, Revere’s legend today has been heavily romanticised, in large part thanks to a 19th-century poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Myth 8: Paul Revere made his ride calling, "The British are coming!"

Revere was just one part of a network that made the late-night ride, and he didn’t even make it the furthest distance. After reaching Lexington, he attempted to reach Concord around six miles (10km) away, only to be detained by a British patrol. It fell to fellow rider Samuel Prescott to complete the journey. Besides, there was little chance any of the riders would have cried out that famous phrase: at that time, the colonists considered themselves proudly British, so what would they have meant by crying out, "The British are coming"?

Myth 9: Pocahontas fell in love with John Smith and saved his life

As the legend – and the Disney movie – go, Pocahontas, daughter of the Powhatan chief, fell in love with a Jamestown settler named John Smith, and saved him from being killed by her own people by bravely putting herself in harm's way. Quite a few details there are wrong. For starters, she was actually called Amonute or Matoaka, and the nickname Pocahontas, meaning 'playful one', had been given to her as a result of her mischievous behaviour. That's because at this time, around 1607, she would have been between 10 and 12 years old.

Myth 9: Pocahontas fell in love with John Smith and saved his life

Smith, who did indeed befriend the child Pocahontas, was notoriously boastful, and only related the story of being saved by her many years later. Did he make it up, or embellish a ritual he observed without fully understanding it? Either way, historians now agree that it never happened, and the two certainly never fell in love. Pocahontas would later be captured by English settlers and spent a year in captivity, during which time she converted to Christianity and took the name Rebecca. In 1614, she was married to John Rolfe – Smith was out of the picture by then – and taken to England, where she died in 1617.

Myth 10: Puritans came to the New World for religious freedom

In November 1620, after more than two gruelling months at sea, the Mayflower landed in New England bearing 102 men, women and children seeking new lives. They had escaped persecution for their Puritan religious beliefs in England – where, they felt, the Protestant church accepted some Catholic ideas and practices too liberally – and hoped that in the Americas they would find religious freedom. However, that doesn’t quite tell the whole story.

Myth 10: Puritans came to the New World for religious freedom

When the Pilgrims left England they initially headed not across the Atlantic, but to the Netherlands. They set up a community there but were still religiously dissatisfied – not because there wasn't enough freedom, but because there was too much of it. The Dutch Republic was too tolerant, and the New World would be a place where they could follow English Puritanism and nothing else. As Massachusetts resident Nathaniel Ward later put it in 1647: "All Familists, Antinomians, Anabaptists and other enthusiasts shall have free liberty to keep away from us, and such as will come to be gone as fast as they can, the sooner the better."

Myth 11: The 'witches' of Salem were burned at the stake

Nowhere in the world is so associated with the paranoia and brutality of witch-hunting than the small town of Salem in Massachusetts. Visitors come in their droves, especially around Halloween, to see where the world's most famous witch trials took place (even though the numbers pale in comparison to the tens of thousands of victims claimed by periods of hysteria in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries). In 1692 and 1693, more than 200 people in and around Salem were accused of witchcraft, 30 were found guilty and 20 were killed.

Myth 11: The 'witches' of Salem were burned at the stake

A common image of the Salem witch trials is of women in typical Puritan dress being burned at the stake. While the burning of accused witches certainly took place in parts of Europe, the punishment in Salem was hanging. Starting with Bridget Bishop, 19 victims died by the noose, while the last victim Giles Corey died while being tortured after refusing to enter a plea. Several more perished in prison from poor conditions and malnutrition. The bodies of the 'witches' were then given unceremonious burials in shallow graves.

Myth 12: Pilgrims and Native Americans came together at the first Thanksgiving

According to the school-friendly version of the first Thanksgiving, the friendly 'Indians', particularly the noble Squanto, taught the struggling Pilgrims how to grow food and adapt to the land during their torrid first winter in the New World. The following year, in 1621, the settlers returned the favour by inviting the local tribe to share in their bountiful second harvest. Today, Thanksgiving is a time of togetherness when families gather to share a hearty meal.

Myth 12: Pilgrims and Native Americans came together at the first Thanksgiving

This mythologised story, however, glosses over the real relations between the English settlers and the Wampanoag. The latter wished to form an alliance not out of friendliness but out of pragmatism, as they were devastated by disease and desperately needed assistance against hostile rival tribes. Thanksgiving did not originate in 1621, but was based on a historical custom already known to the Pilgrims, and the Wampanoags had already had a century of contact with Europeans and European illnesses. And in the long-term, the Thanksgiving myth gives way to a drastically different story: that of centuries of brutal treatment and oppression of Indigenous peoples.

Myth 13: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds caused mass panic

Orson Welles launched himself into the cinematic stratosphere with the 1941 release of his feature film debut, Citizen Kane, but he proved his headline-grabbing storytelling skills three years earlier. On 30 October 1938, he directed and narrated a radio adaptation of HG Wells’s seminal science fiction novel, The War of the Worlds, set on the American east coast and utilising fake news bulletins to add realism to the alien invasion. Famously, for some listeners, it became too real.

Myth 13: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds caused mass panic

There were reports of terrified people filling the streets and phoning loved ones. A woman broke her arm when she fell amid the panic, while another ran into a church proclaiming the end of the world. Newspapers filled their front pages with nationwide hysteria. In truth, these were isolated incidents that didn't come anywhere close to the panic being reported. The papers were keen to discredit Welles's production – radio was eating into the print media's ad revenue, and this was a great opportunity to besmirch the technology. Welles, however, did little to quell the reports, and benefitted greatly from his sudden celebrity.

Myth 14: George Washington chopped down his father’s cherry tree

As the man who commanded the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War and was then elected unanimously to serve as the inaugural president of the United States, the life and deeds of George Washington have been told and retold again and again as part of his unimpeachable reputation as father of the nation. One of his most enduring legends is that, as a boy, he chopped down a cherry tree in his family garden with a hatchet, a new gift he was eager to try out.

Myth 14: George Washington chopped down his father’s cherry tree

When confronted by his father, the young Washington admitted immediately that he was responsible for the damage, saying "I cannot tell a lie". Far from being angry, his father praised his son’s honesty, which he said was worth more than a thousand trees. It’s a charming story that extols Washington’s famous virtues, but there's no reason whatsoever to believe it. The fiction first appeared in a glowing biography of Washington written shortly after his death by Mason Locke Weems – and not even the first edition of the book, but the fifth.

Myth 15: The US became independent on Independence Day

The Fourth of July is among the biggest holidays in the US calendar, a celebration of the day that the American colonists declared their independence from Britain and, by asserting their inalienable rights to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness", founded a nation. It's not surprising that 4 July 1776 was selected for this honour, since it's the date at the top of the Declaration of Independence. But in truth, the more significant date was two days earlier – it was on 2 July that the colonies voted to become a new nation, and it simply took the Continental Congress two days to approve the documentation.

Myth 15: The US became independent on Independence Day

Founding Father John Adams wrote that 2 July would be the "most memorable Epocha, in the History of America". Moreover, the signing of the declaration wouldn't take place until 2 August, and it took even longer for all of the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress to put their name to the hallowed paper. The Revolutionary War was also then in its second year, and the symbolic birth of the United States would have little practical meaning without victory, which wasn't formally achieved until the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Myth 16: The Soviets backed down over the Cuban Missile Crisis

This one is sort of true – but only sort of. In 1962 Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev did send nuclear missiles to Cuba, in the hopes of establishing a nuclear base on America's doorstep. And when those missiles were discovered and the American navy blockaded the island, on the orders of President John F Kennedy, he did command that the missiles be quickly dismantled and removed. However, the retreat – and the entire operation – was not as much of a Russian climbdown as it looked in the American press.

Myth 16: The Soviets backed down over the Cuban Missile Crisis

The American public didn't know it, but Khrushchev had achieved a greater strategic goal. President Kennedy publicly promised not to invade Cuba – a hot topic given the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion the year before – but, behind the scenes, he also promised that America would, after a brief interlude, remove its own missiles from US bases in Turkey. Today the crisis is remembered as the closest the world has come to nuclear war, as its two great nuclear superpowers came closer to direct military conflict than at any other point in the Cold War.

Myth 17: George Washington lived in the White House

The White House is where US presidents live and George Washington was the first US president, so it's easy to assume that George Washington once lived in the White House. In reality, he never had the chance – when Washington became president Washington DC wasn't even the capital, and work hadn't yet begun on the iconic white-columned building. It was Washington's successor, second president John Adams, who was first to call the White House home – moving into the building with his wife Abigail while it was still unfinished in 1800.

Myth 17: George Washington lived in the White House

Instead, Washington started his presidency living in the Samuel Osgood House (pictured) in New York City with his family. It was awkwardly situated and quite small, so the presidential household moved to another residence on lower Broadway in 1790, and then later on to a home in Philadelphia. He did, however, write the first chapter of the White House story – he selected the site for the building in 1791.

Myth 18: The Viet Cong were a scrappy, rag-tag guerrilla group

There's a popular image of the Viet Cong, reinforced by Vietnam War films, as scrappy bands of guerrilla fighters, launching lightning-fast ambushes on well-armed but outflanked American GIs before vanishing into the jungle as quickly as they came. And while the Viet Cong certainly made effective use of guerrilla tactics and terrain, they were no rag-tag group; they were a well-organised and well-equipped fighting force with substantial international support.

Myth 18: The Viet Cong were a scrappy, rag-tag guerrilla group

The Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) together made up a formidable force. Viet Cong operations in South Vietnam were often coordinated by the NVA, and carried out using Russian-made rifles that were more than a match for American guns. China and the Soviet Union channelled billions of dollars of military and economic aid into the communist cause, while China even sent troops into Vietnam in the late 1960s. For firepower the US Army definitely had the edge, but it wasn't the David vs Goliath story sometimes seen on screen.

Myth 19: George Washington had wooden teeth and a white wig

There's a grain of truth in both of these. George Washington did have dental trouble for most of his adult life, and he famously only had one real tooth left at the time of his first inauguration. His troubles started at the tender age of 24, and throughout his life his diary entries are littered with references to aching teeth, inflamed gums and payments to a variety of dental experts. Secondly, those famous portraits aren't lying to you – the president was habitually seen with suspiciously pure-white hair.

Myth 19: George Washington had wooden teeth and a white wig

He did not, however, wear wooden dentures or a wig. He went through several sets of dentures throughout his life, but, contrary to later legend, they were made of varying combinations of ivory, brass, gold, animal teeth and human teeth. This set of dentures remains on display at Mount Vernon, and includes teeth from humans, cows and horses. His hair, meanwhile, was his own. Some of the Founding Fathers did wear white wigs, as was the style at the time, but Washington chose simply to style his hair how he wanted with white powder.

Myth 20: Civil War surgeons amputated limbs without anaesthetic

It's a common Civil War image: the gruff, stoic soldier taking one last swig of whisky before the doctor gets to work, the soon-to-be lost limb held in place by a makeshift tourniquet. Sometimes the soldier is 'biting the bullet', an expression supposedly derived from the practice of giving wounded men bullets to bite down on during horrific battlefield surgeries. It's certainly true that field surgeons faced challenging conditions on Civil War battlefields, and that their field hospitals were brutal, blood-soaked places with a bad reputation among the men.

Myth 20: Civil War surgeons amputated limbs without anaesthetic

Fortunately, however, they did not habitually operate without anaesthetic. The Civil War was not a medieval conflict, and estimates suggest that anaesthetic, usually ether or chloroform, was used in surgeries when possible – accounting for 95% of all Civil War surgeries. Rather less fortunately, amputations were very common during the Civil War. Musket balls and cannon shot were destructive weapons that could horribly maim and mangle limbs, and the war created a whole class of disabled veterans who returned home with empty sleeves and trouser legs.