These are some of the OLDEST man-made structures on every continent

75,000 years of human innovation

Having stood the test of time, some of the oldest man-made structures in the world range from modest huts, megalithic temples and prehistoric pyramids to ancient burial mounds and Aboriginal engineering marvels. Here, we’ve compiled a non-exhaustive list of groundbreaking feats by continent that provide valuable insight into humanity’s long and creative history.

Click through the gallery to discover some of the oldest and most fascinating man-made structures on every continent...

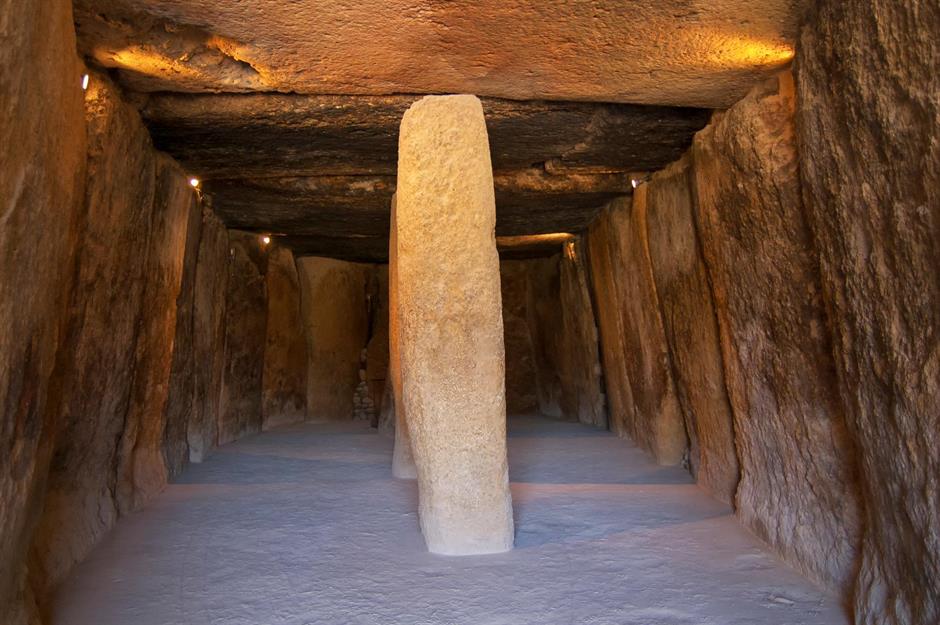

Europe: Dolmen of Menga, Spain

The Menga dolmen is Europe’s largest known megalithic structure, found at the Antequera archaeological site in Andalucia. Dating back to the beginning of the Copper Age (around 2500 BC), the ancient tomb has been hailed as one of the greatest engineering feats of the Neolithic period, built from huge stone blocks to form funerary chambers within an earthen mound. Scientists believe that in order to transport the stones uphill without being damaged, prehistoric humans employed robust grass ropes, specialised knots and wooden scaffolds, as well as the laws of gravity and a whole lot of brawn donated by a team of off-duty farmers.

Europe: Stonehenge, Wiltshire, England, UK

England’s most photographed ancient monument was built in six stages between 3000 and 1520 BC atop the chalky expanse of Salisbury Plain. Though conclusive evidence pertaining to the stone circle’s exact purpose has never been found, it’s generally accepted that it was a religious and ceremonial gathering place, purposefully designed to align with the sun on the solstices. Constructed out of artificially masoned sarsen stone menhirs (large upright stones) and smaller bluestones remarkably transported here all the way from South Wales (some 100 miles/161km away), Stonehenge forms part of a UNESCO World Heritage property together with the Avebury stone circle and its associated sites.

Europe: Newgrange, Ireland

As dawn breaks on the days around the winter solstice, rays of sunlight beam into the interiors of this prehistoric mound. Newgrange, a passage tomb and temple complex in Ireland’s east, is a testament to the craftsmanship of the Neolithic farmers that built it (around 3200 BC) with water-rolled stones from the River Boyne. Covering over an acre, the structure is adorned with 97 keystones around its base, some of which are artfully decorated. Inside, at the end of a narrow corridor, lies a cross-shaped chamber whose corbelled roof is still watertight after 5,000 years.

Europe: Ggantija Temples, Gozo, Malta

These megalithic temples are aptly named for their colossal size – Ggantija meaning ‘belonging to the giant’ in Maltese. According to local legend, it was indeed giants that built these stunning structures, but researchers have more believably attributed their creation to humans, who erected them between 3600 and 2500 BC. Perched on a plateau just outside the Gozitan town of Xaghra, the free-standing chambers once had plastered and painted roofs, but now serve as open-air museum exhibits. The site’s exact function remains a mystery, though one theory suggests it is linked to an ancient fertility cult.

Europe: West Kennet Long Barrow, Wiltshire, England, UK

The West Kennet Long Barrow is one of the most significant accessible Neolithic burial sites in Britain, built around 3650 BC and used for at least 1,000 years. Human remains and grave goods recovered from the area date back to between 3000 and 2600 BC, while evidence of the cemetery’s closure points to 2000 BC – its passages and forecourt sealed off with dirt, rubble and boulders. When originally constructed the barrow would have had bare chalk sides, but today it is concealed under turf.

Europe: Knap of Howar, Orkney, Scotland, UK

On the remote, weather-beaten shores of the isle of Papa Westray, the Knap of Howar is an ancient farmstead (circa 3700 BC) where the oldest standing stone buildings in northwest Europe lie preserved. Similar to those found at Skara Brae – the so-called ‘Scottish Pompeii’, also in the Orkney region – the two interconnecting, hardy structures that make up the Knap of Howar house stone benches, built-in cupboards, hearths and pits within their low, rounded walls, demonstrating the ingenuity and lifestyles of the prehistoric people that designed them.

Europe: Monte d'Accoddi, Sardinia, Italy

Monte d’Accoddi resembles a ziggurat – a pyramidal, stepped temple pioneered by the Babylonians during the 5th millennium BC. But as Sardinia was never part of Mesopotamia, the origins of the structure have fascinated archaeologists for decades. Surrounded by menhirs and other examples of megalithic architecture, the original truncated pyramid has been aged at around 6,000 years old (4000-3500 BC). Unlike traditional mud-brick ziggurats, Monte d’Accoddi was constructed in stone on a carefully arranged foundation. Researchers have surmised that the site, which was built in alignment with the moon, sun and Venus’ position on the horizon, was used for animal sacrifices.

Europe: La Hougue Bie, Jersey, Channel Islands

Constructed sometime around 4000 to 3500 BC, La Hougue Bie is a Neolithic passage grave and burial chamber nestled within an earthen mound on Jersey. Located in the eastern part of the croissant-shaped island, the site was intended for ceremonial as well as funerary use, built to be in tune with the equinoxes. Assembled out of local stones manoeuvred into place with ramps, wooden rollers and raw manpower, La Hougue Bie has been crowned with a (now deconsecrated) chapel since the 12th century, when Jersey shifted from paganism to Christianity.

Europe: Listoghil, Ireland

Listoghil is the largest constructed monument at Carrowmore, a megalithic cemetery in County Sligo. When they excavated the cairn in the 1990s, archaeologists uncovered a platform with charcoal on its surface dating back to 4100 BC, offering an estimate as to when the building of Listoghil began. It is the only limestone-roofed structure at Carrowmore and the only one decorated with megalithic art; all other tombs are plotted around it, suggesting this was the focal point of the cemetery. It is also the only chamber to hold burials as well as cremations.

Europe: Tumulus of Bougon, France

This megalithic necropolis grew to its current size over the course of 1,200 years, between 4800 and 3500 BC. The five distinct barrows represent some of the oldest architectural elements of their kind found on France’s Atlantic coast; the so-called Tumulus E is the oldest mound at the site, with its construction starting around the beginning of the fifth millennium BC. In 1840, Tumulus A was the first to be rediscovered and contains more than 200 skeletons.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for more history, travel and adventure features

Europe: Cairn of Barnenez, France

This early architectural wonder is also Europe’s largest mausoleum, comprising two cairns joined by a subterranean tunnel, containing 11 burial chambers between them. It was constructed on the Breton coast in two phases, with the oldest parts of the site harking back to around 4800 BC. But the Cairn of Barnenez almost didn’t survive into the present day: it was used as a quarry for paving stones in the 1950s, which concurrently nearly destroyed the tumulus and exposed its ancient chambers, leading to its excavation and subsequent restoration.

Europe: Dobrudzha Troy, Bulgaria

At its island home on the Durankulak Lake, the ancient settlement of Dobrudzha Troy was first rediscovered in the 1970s. But it wasn’t until 2015 that archaeologists shared the news of a 7,500 year-old cult complex found at the site. The stone building, attributed to the Hamangia civilisation (an early farming community), would have been larger than a singles match tennis court when newly built and possibly had two floors, which was incredibly rare for its time. It’s thought to have collapsed due to an earthquake.

Europe: Khirokitia, Cyprus

Also spelled Choirokoitia, this prehistoric settlement is said to be the first evidence of settled human habitation in Cyprus. It’s one of the most compelling sites of its kind in the eastern Mediterranean, where low walls and platforms within the circular huts preserved here denote separate spaces for work, leisure time and storage. The people believed to be behind its construction worked in animal husbandry and other forms of agriculture, occupying Khirokitia from around 7000 BC. It is unknown how they reached the island, though some believe it was as a result of Middle Eastern colonisation.

Europe: Catalhoyuk, Turkey

Neolithic Anatolia was the major hub of a progressive culture and the ruins of Catalhoyuk reveal some of its handiwork. Located across two hills near the modern-day city of Konya, this settlement demonstrates the transition from humans living in settled villages to more complex, urban communities. Its unique layout features a streetless agglomeration of back-to-back houses with roof access into the buildings. There’s some discrepancy around the age of the structures at Catalhoyuk; according to UNESCO the site was occupied between 7400 and 6200 BC, while other sources suggest the earliest construction phase began circa 6700 BC.

Europe: Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

Rediscovered in the 1960s, Gobekli Tepe was initially thought to be a medieval cemetery. But closer examination of the site recognises it as a testament to the Aceramic (before pottery) Neolithic age. Erected by hunter-gatherers sometime between 9600 and 8200 BC, Gobekli Tepe contains layers of megalithic monuments which researchers believe could have comprised a sanctuary dedicated to funerary rituals. Other ancient man-made structures found here include T-shaped pillars bearing carvings of wild animals and the remains of domestic buildings.

Europe: Theopetra Cave wall, Greece

Hidden within the otherworldly rock formations of Meteora, Theopetra Cave was likely inhabited by humans as early as 130,000 years ago. While no man-made structure of that age survives to tell the tale, a stone wall built by human hands, which would have once partially sealed off the cave entrance, has been dated to around 23,000 years old. The structure was unearthed in 2010 and coincides with the last glacial age, leading archaeologists to theorise that the cave inhabitants built the wall to shield themselves from the cold.

Asia: Lord Palace of the Kings, Iraq

The Lord Palace of the Kings may only have been discovered in 2022, but it is estimated to be 4,500 years old. Once the heart of the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu, the palace lay under the desert sands of what is now called Tello for millennia before archaeologists from the British Museum unearthed its existence using drone imaging. The Sumerians are one of the oldest Mesopotamian cultures we know of, credited as pioneers of writing, city-building and codes of law, which they are said to have invented between 3500 and 2000 BC.

Asia: Dholavira, Gujarat, India

The structures within this ancient island city in western India were in use between around 3000 to 1500 BC. Comprising the southern centre of the Harappan civilisation – the earliest known urban culture on the Indian subcontinent, Dholavira remains astonishingly well preserved despite its long abandonment. Among the historic structures within its walls are a castle, homes of various sizes and social categories, and six different kinds of cenotaphs marking a sprawling cemetery. The city’s inhabitants even engineered a sophisticated water management system in order for the settlement to benefit from a pair of seasonal streams nearby.

Asia: Shahr-e Sokhta, Iran

One of the largest and richest sites of the Middle Eastern Bronze Age, Shahr-e Sokhta translates as the ‘Burnt City’, having been ravaged by fire three times in its history – the last proving fatal to its position as a habitable city, around 1800 BC. Built on the banks of the Helmand River circa 3500 BC (new research in 2023 revealed it to be 300 years older than originally thought), the city contains walls, vast buildings, graves with headstones and other structures that point to one of the earliest culturally advanced communities in eastern Iran.

These are the world's oldest man-made structures still in use today

Asia: Mehrgarh, Pakistan

Long before the Harappan civilisation built settlements such as Dholavira, there were much earlier peoples erecting structures in the Indus Valley. This is evidenced at Mehrgarh in modern-day Balochistan, where buildings made of sun-baked mud bricks were constructed around 7000 BC, making this the oldest known Neolithic site on the northwest Indian subcontinent. Until circa 5500 BC, Mehrgarh was a humble farming and pastoralist community, with the oldest structures exposed today believed to have fulfilled storage rather than residential purposes.

Asia: Tell Qaramel, Syria

Excavations at this prehistoric Syrian settlement have found it dates back to the proto-Neolithic and early Aceramic Neolithic periods, from the middle of the 11th millennium BC to about 9650 BC. The oldest structures discovered here are five cylindrical towers believed to be the earliest known buildings of their kind in the world. They indicate how societies throughout the Near East simultaneously adopted Neolithic culture, establishing communal enclaves built out of mud and stone, sustained by farming practices.

Asia: Gunung Padang, Indonesia

Gunung Padang has courted a lot of controversy of late, ever since a new scientific study published in 2023 claimed that a pyramidal structure buried beneath its surface could be more than 25,000 years old. This would make it the world’s oldest known pyramid by a significant margin, a notation that has divided archaeological experts. Built atop an extinct volcano in West Java and long deemed sacred by local people, Gunung Padang has historically been regarded as a megalithic structure. But the 2023 study reframes this, placing the oldest parts of the underground pyramid at between 14,000 and 25,000 years old.

North America: Cahokia Mounds, Illinois, USA

Recognised by UNESCO as the largest pre-Columbian settlement north of Mexico, the Cahokia Mounds are all that remains of North America’s first major city, occupied primarily between 800 and 1400 AD. At its peak, Cahokia was larger than London at the time and home to some 20,000 Mississippian peoples. Today, at the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, visitors can see several ancient man-made structures, including 51 platform, ridgetop and conical mounds that would have served as building foundations and funerary tumuli.

North America: La Venta, Mexico

Founded by the Olmec, Mesoamerica’s first elaborate pre-Columbian civilisation, La Venta dates back more than 3,000 years. During the first millennium BC, La Venta was the most important settlement in non-Maya Mesoamerica, comprising several major structures that are all set on an axis eight degrees west of north, suggesting that the builders planned for them to align with the stars at the time. The most imposing man-made feature of the site is a 100-foot (30m) high clay pyramid, which was likely the region’s largest single building on completion.

North America: Serpent Mound, Ohio, USA

Serpent Mound is the largest surviving prehistoric effigy mound (an artificial hump of land shaped like an animal) in the world. Constructed by Native Ohioans around 300 BC, its purpose may have been spiritual, as snakes were often associated with the supernatural in Indigenous American cultures. But as the head and tail of the serpent also align with the sun on the solstices, the mound could have held temporal significance too. Some scholars believe it may have acted as a compass, due to its alignment with Thuban, the north pole star at the time of construction.

North America: La Danta, Guatemala

One of the world’s biggest pyramids lies hidden in the Guatemalan jungle, abandoned along with the rest of the city of El Mirador nearly 2,000 years ago. But La Danta was once the centre of the Maya civilisation – a huge stone temple that would have taken 15 million days of hard labour to build. Dating back to circa 300 BC, La Danta is thought to be the tallest structure ever built by the Maya while El Mirador, former capital of this ancient society, was once home to an estimated 200,000 people.

North America: LSU Campus Mounds, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA

Louisiana State University made the news in 2022 when it was announced that two grassy mounds on its Baton Rouge campus had been identified as North America’s oldest man-made structures. Construction of the mounds took several millennia: Mound B was started around 11,000 years ago, though was reconstructed around 7,500 years ago when work on Mound A began. Built by the Indigenous peoples of Louisiana, the mounds would have aligned toward the red giant Arcturus when completed some 6,000 years ago, one of the brightest stars that can be seen from Earth.

South America: Ciudad Perdida, Colombia

Translating as the 'Lost City', Ciudad Perdida sits concealed by rainforest in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains. It was built by the Tairona people, a pre-Columbian culture of Colombia, around AD 800 and was known then as Teyuna. The historic city is more than 600 years older than Peru’s Machu Picchu and was abandoned around the time of Spain’s colonisation of the region. Today, over 270 terraces of Ciudad Perdida can be explored, featuring the remains of canals, ceremonial areas, houses, plazas, staircases and stone paths.

South America: Tiwanaku, Bolivia

The ruins of Tiwanaku owe their name to the pre-Columbian civilisation that founded a settlement here more than 3,000 years ago. The site, which lies near the southern shore of sacred Lake Titicaca, is home to artefacts that originate from the 2nd millennium BC, though scholars believe most of the major buildings date back to between 200 and 600 AD. One of the most impressive man-made structures at Tiwanaku is the Kalasasaya (pictured), a temple complex surrounding the monolithic Gateway to the Sun, guarded by a carved Doorway God statue.

South America: Caral-Supe, Peru

Constructed by the earliest known civilisation in the western hemisphere, the sacred and architecturally complex city of Caral-Supe (also known as Caral) comprises 1,500 acres of pyramids, plazas and dwellings. The site was dated to around 2600 BC in the 1990s, when the remains of reed-woven bags weighted with stones to support the pyramids’ walls were radiocarbon-tested. Of the six ancient pyramids found here, Piramide Mayor (pictured) is the largest, with a surface area equating to roughly four football pitches.

South America: Sechin Bajo, Peru

Sechin Bajo, located in the Casma Valley of northwest Peru, is a pre-Incan archaeological site home to one of the Americas’ oldest man-made structures. Excavations in 2008 revealed a previously hidden ceremonial plaza built out of stone and adobe, circular in shape and sunken into the ground beneath another piece of architecture among the ruins. Scientists have dated the plaza back to 3600 BC; prior to the discovery, Sechin Bajo was believed to have been occupied between 1900 and 1800 BC.

Australia: Wiebbe Hayes fort, West Wallabi Island, Western Australia

But older still is the Wiebbe Hayes stone fort, believed to be the oldest surviving European structure in Australia. Now just a small collection of limestone and coral blocks, the fort was constructed in AD 1629 in the midst of mutiny. When Dutch East India Company ship the Batavia was steered deliberately off-course by mutinous crew members, it struck a reef off the coast of West Wallabi Island in the Houtman Abrolhos archipelago, and foundered. Soldier Wiebbe Hayes and his fellow survivors then built the inland fort to defend against the murderous mutineers.

Australia: Ngunnhu fish traps, Brewarrina, New South Wales

While the wall at Theopetra Cave is widely accepted to be Earth’s oldest known man-made structure, there are other contenders – including one on the opposite side of the world. The Ngunnhu fish traps of Brewarrina were constructed by Aboriginal Australians across a shallow bend of the Barwon River some 40,000 years ago. Using stones to map out a series of ponds and channels, they would catch fish on their way downstream. The design was adaptable to seasonal changes in the river levels and, according to Aboriginal lore, was inspired by the hunting methods of the pelican.

Africa: Pyramids of Giza, Egypt

Though the Pyramids of Giza are rightly lauded as some of the oldest man-made structures in the world, they are practically infantile compared to most places in this list – even though woolly mammoths still walked the Earth when their foundations were being laid. Constructed as tombs for three pharaohs (Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure) of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty, the limestone pyramids approximately date back to between 2575 and 2465 BC. The Khufu Pyramid, more commonly known as the Great Pyramid, is the oldest of them all and is the only Wonder of the Ancient World still standing.

Africa: Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt

Guarding the necropolis of Giza, it’s widely accepted that the Great Sphinx was hewn from a single block of limestone for the pharaoh Khafre (circa 2603-2578 BC); its face bears more than a passing resemblance to the king, according to a life-size statue of him unearthed in the mid-19th century. But some scholars believe Khufu, Khafre’s father, was the true owner. Historians have also speculated that the Sphinx could have held celestial significance for the ancient Egyptians – possessing the power to channel the sun and the gods to resurrect the pharaoh’s soul.

Africa: Step Pyramid of Djoser, Egypt

Egypt’s earliest monumental pyramid stands in the famed Saqqara necropolis as it has for over four millennia. Built for the Third Dynasty pharaoh Djoser around 2600 BC, it is thought to be the handiwork of the world’s first named architect, Imhotep, who is also later deified as the god of medicine. The six-tiered step pyramid, located just on the outskirts of what would have been Memphis, the ancient Egyptian capital, was originally clad in white limestone. Now, this exposed golden form is what visitors see today.

Africa: Adam’s Calendar, South Africa

Supposedly older than the Theopetra Cave wall and the Ngunnhu fish traps combined, Adam’s Calendar could be the oldest man-made structure in the world. Located in the Mpumalanga province of South Africa, it is a stone circle surrounded by ruined, walled enclosures originally thought to date back to around the 13th century AD. But further detailed analysis has placed the structures at more than 75,000 years old, with some researchers suggesting they could have been built 200,000 years ago. The monoliths of Adam’s Calendar were used to track the months of the year, using shadows cast by the sun.

Antarctica: Borchgrevink’s Huts, Cape Adare

Carsten Borchgrevink was a Norwegian explorer and the leader of the British Antarctic Expedition 1898-1900 (also known as the Southern Cross expedition). In February 1899, Borchgrevink and his nine men spent two weeks erecting a pair of prefabricated structures at Cape Adare, famed for its Adelie penguin colony. The spruce-wood huts, used for lodging and storage respectively, can still be seen today and are the oldest buildings in all Antarctica. The accommodation hut (left in the image) would have housed the entire party, its papier-mache insulation and double-paned window their only protection from the elements.

Now check out these amazing photos of ruins reclaimed by nature