Amazing historic photos of America’s railroads

A train trip through time

As the United States expanded into the Wild West, settlers were transported by a technological advance that changed the face of America: the railroad. Railways would eventually cross both country and continent, linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and helping turn America into the global superpower that it is today.

Click through this gallery to journey back in time to the nation’s first locomotive, steam through the Golden Age of Rail and terminate once again in the present day...

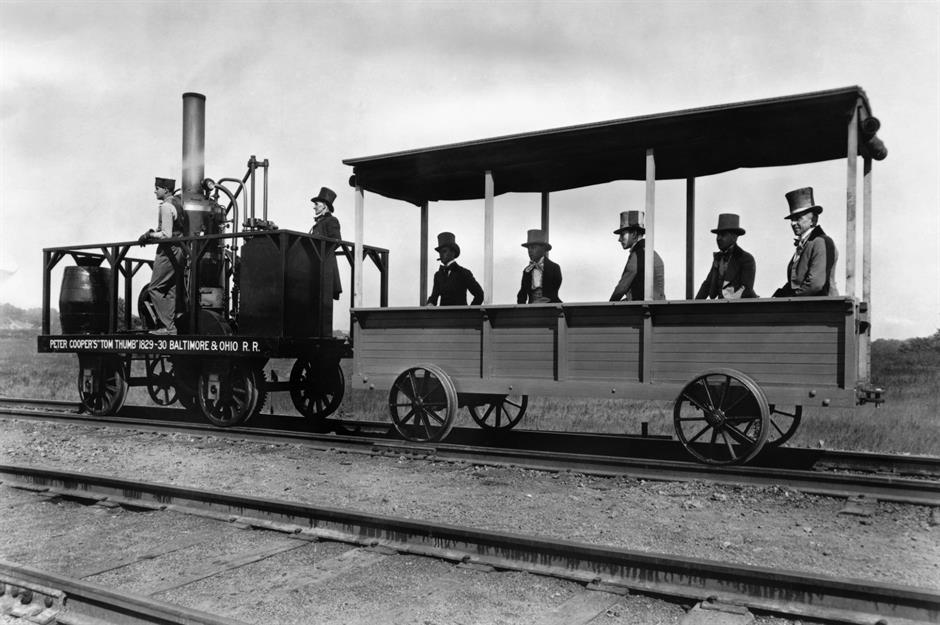

1830: The first steam locomotive

A tiny steam locomotive nicknamed Tom Thumb made history on two counts. In 1829, it was the first steam locomotive built in the USA, crafted by an inventor named Peter Cooper. The following year, legend holds that it carried the directors of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on a test race against a horse-drawn carriage, reaching a top speed of 18 miles per hour (30km/h) and proving the potential of steam-powered rail travel. Though the original engine was scrapped, a replica was built in 1927 and is pictured here recreating the famous race.

1830: America’s first passenger line

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad originally relied on horses to pull its trains, but it became the first American railroad to switch to locomotives in 1830 – although the tracks didn’t actually reach Ohio until 1852. A branch line reached Washington DC in 1835 and the first train into the capital was the Atlantic, a replica of which is pictured here carrying double-decker carriages. The Atlantic was among the first commercially viable locomotives as it boasted superior coal-burning efficiency compared to earlier models.

1862: The railways go to war

By 1860, the United States had more than 30,000 miles (48,000km) of rails, and when the Civil War broke out it became the world’s first railway war. Trains could rapidly transport troops and supplies to the frontline, so soldiers systematically destroyed rails, bridges and rolling stock to hinder the enemy. The rail line near the federal armoury at Harper’s Ferry (pictured here during the war) came under repeated attack.

1865: Reconstruction

By the end of the Civil War America's railways, like the rest of the nation, required reconstruction. The South was particularly badly affected, partly because Confederate saboteurs destroyed their own lines to try to halt the Union advance. Repairs were often hastily carried out by military engineers, as with this bridge on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Photographed in 1865, the bridge is just about being supported by a rudimentary-looking patch. Thanks to this sort of work, lines could sometimes be back up and running within hours of an enemy attack.

1869: The first transcontinental railroad

Soon, the railways were expanding even more quickly than they had before the Civil War. After peace was declared, work accelerated on the biggest civil engineering project America had ever seen – the transcontinental railroad. Stretching from Omaha in Nebraska to Sacramento in California, the 1,776-mile (2,858km) line was built by speedy track-laying crews who were incentivised to lay one to two miles of track per day. Labourers worked in all weathers to ensure the work was completed in a timely fashion.

1869: The golden spike

On 10 May 1869, the railway's eastern and western construction crews met in the middle, on a patch of high ground in Utah known as Promontory Summit. Here, the management of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads met for a celebration (pictured) and drove a ceremonial golden spike into the ground to mark the exact point the tracks touched. From now on, Americans could travel from sea to shining sea by a single mode of transport: the railway.

1870s: A diverse workforce

Thanks to shortages in manpower after the carnage of the Civil War, railroad construction crews lacked a steady supply of cheap labour. The solution came from overseas. Irish immigrants on the East Coast regularly moved inland to find jobs laying rails, while in the west often poorly-treated Chinese migrants were a cheap solution. More than 10,000 Chinese labourers helped to build the first northern transcontinental line. Here Chinese labourers work their way along the Northwest Pacific Railway on a handcar, sometime in the 1870s or 1880s.

1876: Extraordinary engineering

When the Union Pacific Railroad reached the seemingly impassable Dale Creek, Wyoming in 1868, they initially breached the gap with a wooden trestle bridge – but it was a rickety structure. Two carpenters fell from the bridge to their deaths, and it swayed alarmingly when trains passed over it. In 1876 the original crossing was replaced by an iron bridge, pictured here in 1885. The spindly legs did a much better job of holding up the tracks, although trains still had to slow to 4 miles per hour (6km/h) when crossing.

1877: Rail riots

Railway work was poorly paid and dangerous, but that didn’t stop bosses trying to squeeze wages even lower. In 1877, workers snapped and went on strike and the heavy-handed government response was to send in the troops. The deaths of 20 strikers in Pittsburgh helped cause a riot that targeted railway property. The damage was substantial – as seen in this picture of the destruction at the Pennsylvania Railroad Roundhouse – but the riots eventually petered out and the strikers were forced to return to work with no pay rise.

1880s: Rail empires

By the 1880s, industrialists like Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt and JP Morgan made fortunes by sinking vast sums of money into railroads and slowly gaining a monopoly on rail travel. Small, regional lines were consolidated into giant rail empires headed by men whose astonishing wealth and sometimes-questionable business practices meant they became known as 'robber barons'. Lines continued to expand as money was pumped into new track and infrastructure, like the new bridge crossing over the Green River in Washington, pictured here in 1885.

1885: The death of canals

The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company had transported coal in New York State since 1828, but by the 1870s water transport was slow and unprofitable. Instead, the managers of the D&H transitioned into rail transport. By 1885, when this photograph was taken in the Drake Street engine house in New York, the company’s rail lines stretched across the state and beyond, and it abandoned the obsolete canal in 1898.

1886: Frontier wars

The westward migration of white settlers into the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains brought them into conflict with the Native American tribes that had lived there for millennia. Transcontinental railroads became a target for native raids, but trains helped the US Army respond quickly to attacks and brutally subjugate the tribes who fought to defend their lands and way of life. Here, Chiricahua Apache prisoners including famous native leader Geronimo are pictured outside a rail car in 1886, on a journey from Texas to Florida as part of a forced relocation.

1887: 'Hell on Wheels'

As the railroads passed through long stretches of empty plain, construction crews carried everything with them to ensure work continued in often hostile environments. Track-layers lived in tent communities that followed the rails, accompanied by pop-up saloons, dance halls, gambling houses and brothels. The owners of these lawless establishments were keen to separate the workers from their wages, and the itinerant communities soon garnered the nickname 'Hell on Wheels'. This image shows the construction of a railroad in Montana in 1887.

1890s: Going up

While rail tracks encroached further and further into the Wild West, railways were also taking over the cities of the East Coast, and to keep their urban footprint as small as possible engineers built into the sky. New York’s first elevated railway opened in 1878, and it was joined by Chicago’s first (pictured here) in 1892. Known as 'els', these raised tracks arrived in Boston in 1901 and in Philadelphia in 1907. The high-rise rails were not to everyone’s tastes, however, and many were later pulled down to be replaced with underground subways.

1894: The Pullman Strike

Railway building proved so lucrative in the 1880s that almost every mogul got in on the action, but the bubble burst in 1893 when a financial crisis rocked Wall Street and many railroads went bankrupt. Workers felt the brunt of the pain again and it pushed many to go out on strike. The government backed big business over the workers and sent in the troops to protect railway property, like the soldiers here patrolling the Rock Island Railroad in Illinois.

1895: Electrification

By the end of the 19th century, steam trains were becoming a public enemy in city halls across the country and several towns and cities attempted to crack down on smoke levels. The eventual solution was the electrification of metropolitan railways and tramways. The Baltimore and Ohio became the first line to use electrical passenger trains in a three-mile (5km) stretch of tunnel in 1895 (pictured here in 1896). Electrification came at significant cost and required all-new rolling stock, so it would take many more years to become the industry standard.

1896: Welcome to Miami

The railroads gave birth to several cities that wouldn't otherwise exist in their current form. The Florida East Coast Railway was initially supposed to run from Jacksonville to Palm Beach, but bosses decided to extend it another 75 miles (120km) south to Miami, then a sleepy fishing village with a population of 300. In 1896, this train was one of the first to steam into Miami, kickstarting the city’s rapid growth into one of America’s most popular vacation destinations.

1900s: The golden age of rail travel

The dawn of the 20th century saw the beginning of a period now known as the golden age of rail travel in the USA. Profits boomed as the railways reached a peak of 254,251 miles (409,177km) of track in 1916, while wealthy first-class travellers enjoyed unprecedented levels of luxury. Pictured around 1905, this passenger is enjoying a comfortable bunk in a sleeper carriage.

1906: A pillar of the economy

The railway industry didn’t just prop up the American economy by transporting passengers and goods – it employed millions of Americans too, both on the railroads themselves and in allied industries. By 1906 the Baldwin Locomotive Works (pictured here some years later) employed 17,000 people working round-the-clock shifts and had the capacity to produce 2,500 new locomotives a year.

1910: Going underground

Building railroads through the wilderness was challenging, but squeezing them into fast-growing cities on the coasts came with an entirely different set of problems – mainly a lack of space. In New York, passengers on the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated their journeys west of the Hudson River and had to get a ferry into Manhattan. That inconvenience ended in 1910 with the completion of a tunnel under the Hudson and Penn Station, pictured here during construction. On opening, a thousand trains flooded into the station every weekday.

1917: Government takeover

By 1917, the American railroad system was beginning to show its age – and it couldn’t have come at a worse time. The USA had just joined the First World War, and rail infrastructure was going to be vital for troop mobilisation and transporting supplies. The government stepped in by temporarily nationalising the railroads, pouring money into updating and standardising tracks, stations and rolling stock. Three years later the railroads were transferred back into private hands, although the government retained an increased level of oversight.

1930s: Planes, trains and automobiles

During the interwar years the railroad industry faced increased competition from two fast-growing modes of transportation: road vehicles and planes. While the government hampered railroad operation with red tape and regulation, it also aided the competition by pouring vast sums into highways and airports. As trucks began transporting freight, and cars, buses and planes aided the movement of people, the railways endured the Great Depression of the 1930s under a level of sustained pressure they’d never felt before.

1934: Streamlining

With competition rising, railroads needed a new innovation to fight back. They got one with streamlined trains. These rapid locomotives ran at increased speed by cutting wind resistance, made trains more efficient and cheaper to run, and helped add a modern feel to a mode of transport widely viewed as old-fashioned. For a short period in the late-1930s the 10 fastest train services in the world were all American streamliners. This image shows one of the first and fastest streamliners – the Commodore Vanderbilt, built in 1934.

1950s: A new power

Streamlined steamers were only temporarily in fashion, and by the mid-1950s a new form of engine had taken over the rails. Diesel locomotives had been around for a while, but only grew to truly dominate the rails through the late-1940s and 1950s. They were more expensive to build than steam engines, but were easier to maintain and required only one driver. The cost and reliability of diesel engines like this one on the Canadian Pacific gave rail a fighting chance in a competitive freight transport industry, and the success of diesels ultimately condemned steam locomotives to the scrapheap.

1950s: New standards of comfort

In the battle to keep commuters out of cars, railroad bosses tried to redefine the passenger experience with more comfortable carriages. The Pennsylvania Railroad spent millions on new lightweight carriages (pictured here in 1956) with lowered floors that enabled them to take corners more quickly. The only problem was that passengers hated them – the split-level stairs tripped people up and bottlenecks formed at the doors.

1960s: Turbotrains

In the late 1960s rail travel entered the jet age with a new piece of kit: the Turbotrain, pictured here in 1968. Built by an aircraft manufacturer, Turbotrains were powered by gas-turbine engines similar to those found on airliners and featured tilt technology to take corners at high speed. Despite the cutting-edge tech, Turbotrains were scrapped after only a few years thanks to increasing fuel costs during the global oil crisis.

1971: Amtrak is born

By the end of the 1960s, the railroads were in crisis once again. Many smaller railways were driven out of business thanks to the relentless expansion of car ownership, and even the bigger railroads were not immune. After the Penn Central rail company became America's biggest ever corporate bankruptcy in 1970, the government was forced to step in. The result was Amtrak, a semi-public corporation that was subsidised by taxpayers to take on several bankrupt lines and rebuild America’s aging rail infrastructure. This image shows passengers strolling beside a typical Amtrak train in New Mexico in 1974.

1980s: Rebuilding the fleet

Amtrak’s efforts to rejuvenate rolling stock and stations did not significantly boost passenger numbers, which remained relatively stable between 1980 and 2000. It had more success in reviving freight traffic, however. Restrictive regulations were binned, allowing operators to concentrate on profitable lines and alter timetables to make networks more efficient. New trains like the electric-powered AEM-7 (pictured here in 1987) became workhorses of the Amtrak fleet. Now, rail carries 40% of America’s freight – more than any other form of transport.

2024: Looking ahead

The present-day rail network continues to transport freight across the country in vast quantities. Politicians have long promised to win back passengers with announcements about high-speed lines, integrated infrastructure and modernisation. But, for now, American rail seems likely to remain a freight-first business while ordinary Americans opt for their automobiles to get from A to B.

Now discover these amazing images from the golden age of flying