The fascinating and tragic story of Neuschwanstein, Germany’s most beautiful castle

A royal swansong

Set at the edge of the Bavarian Alps, Neuschwanstein Castle (pronounced ‘noy-schvaan-stine’, in case you were wondering) looks lifted straight from a story book. But its fairy-tale facade belies a past marred by the torment and tragedy of the man who commissioned it, King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Since his untimely death prompted Neuschwanstein’s swift opening as a tourist attraction in 1886, millions have travelled from all over the world to lay eyes on the passion project Ludwig never saw realised.

Click through the gallery to uncover the bittersweet story of Germany’s most visited castle...

Family business

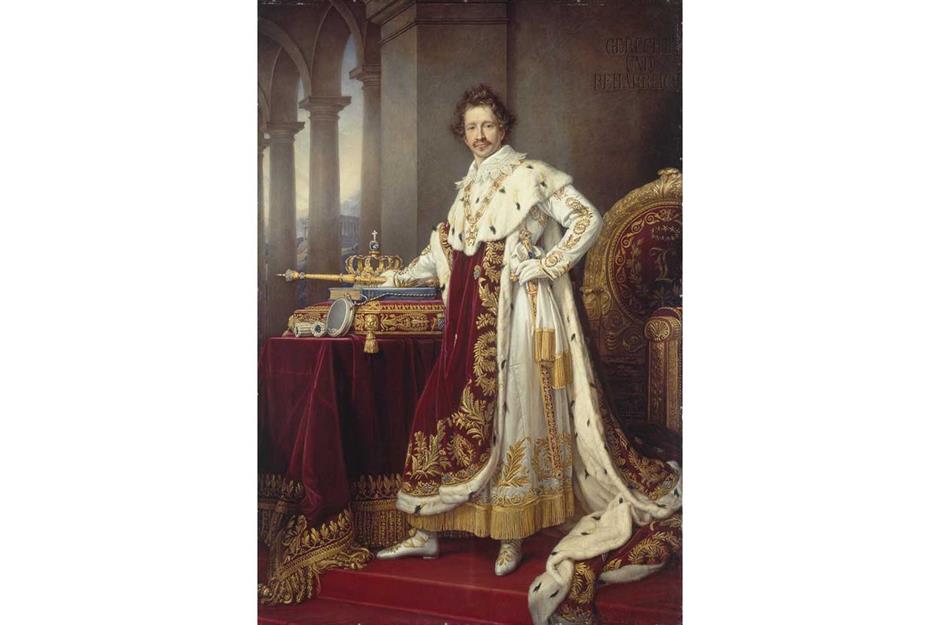

The state of Bavaria, which covers the entire southeastern corner of Germany, was its own kingdom from 1805 to 1918, until its last king (Ludwig III) was overthrown by republicans. The boy who would later become Ludwig II of Bavaria was born on 25 August 1845 and given the regnal name as his grandfather, King Ludwig I (pictured), wished. Ludwig I, godson of Louis XVI of France (Ludwig being a German form of Louis) was forced to abdicate in 1848, with the throne passing to his eldest son Maximilian.

Childhood memories

King Maximilian II and his wife, Marie of Prussia, spent their summers at Hohenschwangau Castle (pictured) with their two sons. Crown Prince Ludwig grew enamoured with the castle’s dramatic alpine surroundings and it quickly became one of his favourite places to stay. Inside, the walls of Hohenschwangau were adorned with painted scenes from medieval legends and poetry, including the swan knight Lohengrin, with whom Ludwig developed a particular affinity. A lifelong lover of make-believe, it’s no wonder the shy young dreamer came to favour fantasy over reality.

The fairy-tale king

Despite their lavish holidays together, the royal family were not especially close. The king and queen kept Ludwig and his brother Otto at arm’s length, raising them for the responsibilities they were born to inherit. Then in 1864, when Ludwig (pictured) was just 18 years old, his father died unexpectedly. Inexperienced and overwhelmed, Ludwig became King of Bavaria and never quite adjusted to life in the public eye. As a boy, he once told his governess: “I want to remain an eternal mystery to myself and others."

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for more stories on travel and tourist attractions

Political palaces

Just two years into his rule, Ludwig entered the Seven Weeks’ War on the side of Austria, but suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of Prussia, which was fast becoming a super-power. As a result, Bavaria was forced into an alliance with Prussia that gave the latter control over the former’s foreign policy. Ludwig, having lost autonomy over his kingdom overnight, set about building his own. His obsession with elaborate and expensive construction projects consumed the rest of his life, filling the void left by his stolen sovereignty.

A study in historicism

One of these projects was Neuschwanstein, which Ludwig referred to as “New Hohenschwangau Castle” (the name ‘Neuschwanstein’ was only acquired posthumously). It was the king’s plan to replace two old ruined castles adjacent to old Hohenschwangau with the new residence, which he envisaged as an ideal replica of a medieval castle with all the mod cons of the mid-to-late 19th century. Combining inspiration from the iconic Wartburg in Eisenbach to book illustrations from the Middle Ages and theatrical set design, Neuschwanstein is regarded as an example of historicism – a pastiche architectural style based on those from bygone eras.

For the love of Wagner

When he was still in his teens, Ludwig discovered a fondness for the music of Richard Wagner, having seen the operas Lohengrin and Tannhauser (pictured) for the first time in 1861. As an adult, he befriended the composer and brought him under his patronage, with Wagner describing the king as a “divine dream in a base world.” Ludwig wrote to Wagner of his designs for an idyllic new castle near his once-beloved Hohenschwangau, whose interiors would pay homage to the composer’s works. The king ultimately dedicated Neuschwanstein to Wagner.

Neuschwanstein is born

Work to establish the future castle’s building site began in the summer of 1868, on a ridge set high above the Pollat Gorge and backed by majestic mountains. On 5 September 1869, the foundation stone for Neuschwanstein was laid, with the castle’s blueprints, portraits of Ludwig II and coins from his reign incorporated – a tradition started by the king’s grandfather. The latest construction techniques and materials were used to bring Ludwig’s vision to life, with cement foundations and brick walls clad in ivory limestone. Ludwig expected to move in within three years. This image dates to around 1875.

Slow progress

But it all took much longer than the king anticipated – the castle’s mountain setting presented logistical difficulties and Ludwig’s deadlines weren’t sympathetic to the scale of the project. The Gateway Building, which had its topping-out ceremony in 1872, was the first section of Neuschwanstein to be completed. The king had temporary accommodation established on its upper floor that he lodged in from 1873 when visiting the site, but Ludwig would never enjoy his dream home without scaffolding holding up some part of it. This is how it looked at the time of his death in 1886.

Moving day

After the Gateway Building was finished, next on the construction schedule was the king’s palas – a residential part of the castle that contained a great hall. Work commenced in 1872, with a spectacular, double-height Throne Hall (pictured) – its groundbreaking steel framework encased in plaster – added later at the king’s behest, complete with murals of canonised kings. Convinced he was ordained by God and viewing his kingship as a holy mission, Ludwig used the Throne Hall not as a space to give audiences, but as a vessel through which to exercise and explore his perceived divinity. The palace had its topping-out ceremony in 1880, and Ludwig moved in in 1884.

More regal rooms

One of the design ideas Ludwig borrowed from the Wartburg was the Singers’ Hall, though he wanted the one at Neuschwanstein (pictured) to be even larger and more impressive. A tribute to the medieval knights and sagas that had bewitched the starry-eyed king since his youth, the hall never actually hosted any festivities, but was a private sanctuary for the royal recluse. As he grew increasingly more isolated, Ludwig changed his mind about the function of certain rooms in the castle. For instance, his writing room was transformed into an artificial grotto with a secret door leading to a conservatory.

Modern technology

Despite his fascination with the Middle Ages, the king liked his contemporary creature comforts too. Central heating was fitted throughout Neuschwanstein, with running water supplied to every floor and flushing toilets serving the royal residence. The castle was even connected to telephone lines, which at that time were a very new invention. The electric bell system pictured here was introduced by Ludwig to summon his staff, who could deliver his meals from the kitchen via an elevator.

Medieval myths

Many of the king’s favourite Wagnerian operas were adaptations of medieval legends and sagas, which went on to inspire the picture cycles decorating Neuschwanstein’s walls and ceilings, created by Hyazinth Holland. They immortalise several characters that Ludwig identified with, namely the poet Tannhauser, the swan knight Lohengrin and the Grail King Parzival, Lohengrin’s pious father. Depicting themes of love, guilt, repentance and salvation, the paintings can be found throughout the castle, including in the Singers’ Hall, the salon and the study. Scenes of the doomed lovers Tristan and Isolde loom over Ludwig's bedchamber (pictured).

The swan knight

Of all the Germanic and Nordic legends from the Middle Ages to find a home in Neuschwanstein’s murals, Lohengrin the swan knight (pictured) is the most significant. Swans (German: schwane) were a leitmotif of Ludwig’s life and legacy, being the heraldic animal of the counts of Schwangau – whom the king considered his predecessors. Ludwig’s father shared this reverence of swans, having made them part of the fabric of Hohenschwangau. As well as signifying this ancestral connection and Ludwig’s idolisation of the fictitious Lohengrin, swans were seen as a Christian symbol of purity.

Ludwig lost

Struggling with being a constitutional monarch instead of a sovereign ruler, Ludwig mostly withdrew from handling affairs of state, preferring to escape to the romantic world of his own making, where his role as king remained as he’d imagined it would be. From 1875, Ludwig chose to live nocturnally, being so active at night that he would often take sleigh rides in the dark. With Bavaria facing bankruptcy, bailiffs threatening to seize his property and his grip on reality slipping, the king was declared unfit to govern and deposed in 1886.

Tragedy strikes

Ludwig was then interned in Berg Palace, on the banks of Lake Starnberg, on 12 June 1886. A day later, he was found dead along with his psychiatrist. While it was officially ruled that the king had taken his own life and that the doctor had died trying to save him, the circumstances of their deaths remain shrouded in mystery. Tragically, this meant that neither the Fairy-Tale King nor his muse ever saw Neuschwanstein Castle finished – Richard Wagner died in 1883.

Opening up

While Ludwig was alive, he never dreamt of allowing outsiders at Neuschwanstein. Designed purely as a place of retreat, the castle’s location was chosen because it was “holy and unapproachable.” But on 1 August 1886 – just seven weeks after the king’s passing, the building opened to the public in its still-unfinished state, and has remained so ever since. Nowadays, there are up to 6,000 daily visitors at Neuschwanstein during high season, passing through rooms that were only made for one.

Forever incomplete

Today, more than 150 years after the castle’s foundations were laid, Neuschwanstein is still not complete. Its southern part was only finished in the early 1890s, while features such as the Bower and the Square Tower are only simplified versions of what the king had intended. Several of Ludwig’s designs, including his chapel keep, a ritual ‘knight’s bath’ and a ‘Moorish Hall’ were never built. But despite not fully matching the king’s lofty expectations, this Romanesque beauty still captures the imagination of around 1.4 million visitors each year, making it Germany’s most visited castle and one of the most popular in Europe.

Disney magic

With its navy-blue turrets and Juliet balconies, it was only a matter of time before Neuschwanstein caught the eye of another eccentric dreamer. The pile is said to have inspired the castle in Walt Disney's Cinderella (1950), whose image also became the logo for the famous film studios and a landmark of Florida's Magic Kingdom theme park. But representatives of Disneyland in Anaheim, California later confirmed that Neuschwanstein – visited by Disney on a trip to Europe – actually influenced its Sleeping Beauty Castle (pictured).

Neuschwanstein on the silver screen

But Disney isn’t Neuschwanstein’s only connection to Hollywood. One of its most notable appearances on the silver screen was in the 1968 movie musical Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (pictured), which follows the escapades of a struggling inventor (played by Dick Van Dyke), his family and their magical flying car. In the film, Neuschwanstein Castle doubles as the home of the fictitious Baron Bomburst of Vulgaria. It also appeared in The Great Escape, in the background of the classic scene featuring Steve McQueen on his motorbike.

Alpine admin

While the setting of Neuschwanstein Castle couldn't be more picturesque, it is also at the mercy of the elements. Nestled in the foothills of the continent’s longest mountain range, the castle’s foundation area is regularly monitored for movement caused by the geology of the Alps. The rock walls supporting its base must also be repeatedly reinforced, while the building's delicate limestone facade has to be painstakingly renovated, section by section, due to environmental effects.

Ludwig’s lavish homes

Aside from Neuschwanstein, King Ludwig II was working on a whole portfolio of royal retreats, including one to rival the Palace of Versailles. In his bid to achieve such an undertaking, the king acquired Herreninsel, an island on the Chiemsee – Bavaria’s largest lake – in 1873 and began building his Bourbon-inspired Baroque complex there five years later. But, like his Alpine bolthole, Herrenchiemsee Palace (pictured) was never finished. At the time of Ludwig’s death, the project had cost more than Neuschwanstein and Linderhof (the only completed home he occupied) put together.

Dreams in stone

These royal refuges – among others all closed to strangers during Ludwig’s lifetime – have now been visited by more than 130 million people. Neuschwanstein Castle, Linderhof Palace (pictured), the King’s House on Schachen and Herrenchiemsee were added to UNESCO’s World Heritage Tentative List in 2015, on account of their striking architecture and the ideal poetic world of kingship they represented to Ludwig. By the summer of 2025, it should be known whether the opulent palaces have received full designation as a World Heritage Site.

Take in the view

The Marienbrucke bridge hangs above the Pollat Gorge today as it has since the 1840s, though it has undergone several facelifts since then. The original was commissioned as a birthday present from Ludwig II’s father Maximilian to his adventurous queen, who loved to climb the mountains around Hohenschwangau. Nowadays, the bridge offers the perfect vantage point from which to snap a photo of Neuschwanstein. From the parapets of the castle itself, you can see out to turquoise lakes and look down on Hohenschwangau, which lies in Neuschwanstein’s shadow.

Restoring a masterpiece

The castle’s popularity with tourists, combined with the stress caused by the alpine climate and light to the precious furniture and textiles inside, mean that conservation is a full-time job at Neuschwanstein. Since 2017, a large-scale and meticulous restoration project has been gradually retouching the intricate artwork of the murals throughout the building. With the renovation of the Singers’ Hall and Throne Hall already finished, the entire project is set for completion later in 2024.

Visiting today

While it was never fully completed, there are 14 rooms inside Neuschwanstein Castle today that are open to the public. The unfinished rooms on the second floor of the building now house a shop, a cafe and multimedia room. Access to Neuschwanstein is available only by guided tour at a fixed time, which you can book online or in-person at the ticket office in Hohenschwangau on the day you wish to visit. The castle’s current opening hours are 9am-6pm, changing to 10am-4pm from 16 October.

Now discover which world-famous landmarks took the longest to build