Vintage photos from gold rushes around the world

Eureka!

In the latter half of the 19th century it seemed the whole world was gripped by gold fever. Telegraph wires hummed with tales of easy fortunes to be made in far-flung corners of the world – America, Australia, South Africa and more – and thousands of men and women flocked to newfound goldfields in the hope of striking it rich.

Click through this gallery to see evocative images of gold rushes around the world – and the transformations they brought…

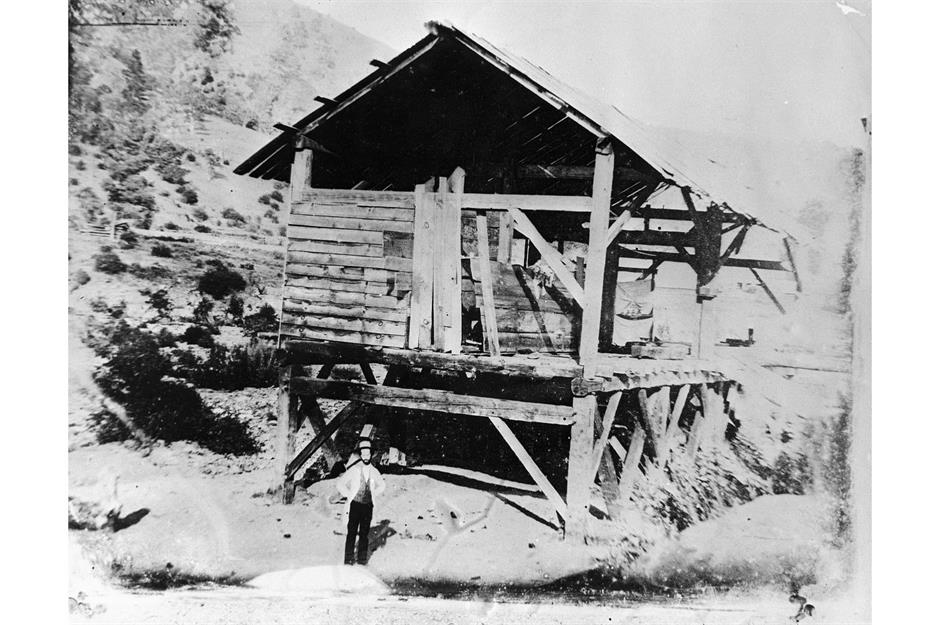

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

The first major gold strike in North America occurred in Dahlonega in Georgia in 1828. But it wasn’t until carpenter James Marshall found flakes of gold in a stream while building a mill for John Sutter in Coloma in 1848 that gold fever really gripped the country. "It made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold", recalled Marshall, seen here standing in front of the famous mill around 1850.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

The owner of the land, John Sutter, had hoped to keep the find a secret. He was a Swiss immigrant and feared the impact a gold rush would have on his grand plan to build an agricultural empire that he'd already christened 'New Helvetia'. His fears were well-founded: the news leaked and within a few months thousands of prospectors had overrun his property, destroying much of his equipment and virtually bankrupting him. Here we see prospectors on the American River, which ran through his property, barely three years later in 1852.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

In fact, the California Gold Rush triggered the largest mass migration in US history. News of the discovery was initially greeted with scepticism on the East Coast, but, when President James Polk confirmed the "accounts of abundance of gold" in December 1848, a great exodus began. In March 1848 there were roughly 157,000 people in the California territory – and fewer than 800 of them were non-native settlers. Twenty months later, that number had soared to more than 100,000, helping California achieve full statehood in 1850. This photo shows a crowd of miners covering a California hillside, and was taken around 1852.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

1849 saw the greatest influx of would-be gold miners into California. Men from all over the country mortgaged their properties or spent their life savings to make the arduous journey west, often leaving their wives and children to run their farms and businesses. They became known as the '49ers – today the name of San Francisco's NFL team – and often spent what little money they had on the rudimentary equipment they needed to 'strike it rich'. This photo shows soldier-turned-miner George W Northrup seated with his tools and a bag of gold.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

A surprising number of early prospectors came from the East Coast by ship. As this photo of Yerba Buena Cove in 1850 shows, many of these ships were simply abandoned after making the treacherous journey around South America, as their crews insisted on heading to the goldfields too. As San Francisco boomed, the ships were dismantled and used as building materials or sunk and used as landfill. More than 170 years later, archaeologists are still finding relics and even entire ships underneath the streets of downtown San Francisco.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

The California Gold Rush was an international event that attracted prospectors from as far afield as Hawaii, Chile and Peru. News of a 'gam saan' (gold mountain) soon reached China, and by 1851 more than 25,000 Chinese immigrants had fled poverty in their homeland to seek their fortune in California too. Mark Twain described the Chinese prospectors as "industrious as the day is long", but they immediately faced discrimination and violence. Multiple taxes were imposed on non-American workers, and the 1852 Foreign Miners Tax included a monthly levy explicitly targeted at the Chinese.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

San Francisco was transformed by the Gold Rush. Before the influx it was a sleepy port town where fewer than a thousand fishermen and whalers lived in wooden shacks around the waterfront. By 1849 it was the gateway to the goldfields and home to a staggering 25,000 people. Hotels, stores, saloons and gambling halls quickly followed, and were eventually joined by stately civic and mercantile buildings funded by taxes and profit. This 1866 photo shows a bustling Montgomery Street – built on land reclaimed along the shoreline of Yerba Buena Cove.

1848-1855: California Gold Rush, USA

While a handful of prospectors did succeed in 'striking it rich', it was merchants who were making the real money. Sam Brannan built the first store near Sutter’s Fort and was quickly raking in $2,000 (now roughly $80,000/£63,000) a day. Others turned their fledgling enterprises into titans of American industry. John Studebaker, founder of the Studebaker automobile corporation, got his start selling wheelbarrows on the goldfields. Henry Wells and William Fargo founded banking giant Wells Fargo in California in 1852, while these two miners in Placer County in 1882 are modelling jeans made by one Mr Levi Strauss.

1851-1880: New South Wales Gold Rush, Australia

Gold was first discovered in Australia by a surveyor near Bathurst in New South Wales in 1823, before surfacing again in the 1840s. The colonial government suppressed the news fearing that the predominantly convict population would abandon their duties to seek their fortune. But when people started leaving for the goldfields of California in 1848, the government changed its position and offered a reward for the first person to find payable gold. In 1851 Edward Hargraves (pictured) found 'a grain of gold' in a billabong near Bathurst, and Australia’s very own gold rush began.

1851-1880: New South Wales Gold Rush, Australia

Hargreaves had just returned from an unsuccessful stint in California, and was struck by how much the gullies around Bathurst resembled the Californian goldfields. Within days of his find becoming public, hundreds of prospectors were searching for gold, with the Bathurst Free Press declaring that "a complete mental madness" had seized every member of the community. Within a month there were over 2,000 people digging around Bathurst, and the rush spread to nearby towns like Gulgong, pictured here.

1851-1880: New South Wales Gold Rush, Australia

The New South Wales Gold Rush got a second wind in 1872 when Bernhardt Holtermann found the world’s largest specimen of reef gold near Hill End. The monster 285kg (628lb) slab of gold-infused quartz stood 4.76 feet (1.45m) high and contained 93kg (205lbs) of gold. It became known as the Holtermann Nugget, and Holtermann used this photo to publicise his find and promote Hill End as "the richest quarter mile in the world". At its peak, the town boasted 8,000 residents, 28 pubs and an oyster bar, despite being 134 miles (216km) from the sea.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

In 1851, faced with the prospect of its population flooding north to New South Wales, the newly formed colony of Victoria offered a reward of £200 – a vast sum today – to anyone finding gold within 200 miles (322km) of Melbourne. Within six months gold was discovered in Clunes, and then in Ballarat, Castlemaine and Bendigo. Reportedly, when the first miners arrived on the Mount Alexander goldfield near Castlemaine, they could just scrape back the soil to discover nuggets of gold.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

The Victorian gold rush quickly outpaced the rush in New South Wales and by the mid-1850s was accounting for more than a third of the world’s gold production. Ballarat was a particularly rich field. Victoria’s Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe visited the area just after the rush began and saw a team of five men unearth 136 ounces of gold in one day and another 120 ounces the next. These finds alone were worth around 10 years' wages for an average Englishman.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

It wasn’t long before the colony became a magnet for fortune-seekers the world over. "It was as if the name BALLARAT had suddenly been written on the sky," wrote Mark Twain. As a British colony, Victoria sent huge sums of money back to Britain in the late 1850s, which was used to pay off foreign debts. Melbourne became one of the richest cities in the world, its wealth reflected in grand buildings like the Oriental Bank building, pictured here in 1858.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

Among the most extraordinary finds on the Victorian goldfields was the Welcome Stranger nugget, dug out from a tangle of tree roots near Moliagul on 5 February 1869 by British miners Richard Oates and John Deason. It weighed 72kg (159lbs) and was 24 inches (61cm) long, and remains the largest gold nugget ever found. Here we see other miners and their wives posing with Oates and Deason, doubtless hoping that some of their good fortune would rub off.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

The influx of migrants from across the world saw Australia’s population quadruple from 430,000 people to 1.7 million between 1851 and 1871. As with the California Gold Rush, one of the largest immigrant groups were the Chinese. Also as with California, they specialised in working over soil that had already been discarded by other miners and faced discrimination and abuse. Here we see a coach load of Chinese workers heading to the Victorian goldfields around 1860, a large cargo of woven bamboo hats attached to the back of the carriage.

1851-1869: Victorian Gold Rush, Australia

The gold rush in Victoria helped transform Australia from a penal colony to a vibrant nation built on values of fairness and 'mateship', expressed here in this image of miners in Upper Dargo. They were values forged in blood at the Eureka Stockade, when miners in Ballarat rose up against punitive licensing laws at the end of 1854. They were defeated by government troops and suffered heavy losses, but from that day they only paid tax on gold they actually found, instead of paying large sums for licenses to work on shrinking fields.

1861-64: Otago Gold Rush, New Zealand

On 20 May 1861, New Zealand was gripped with gold fever when the Australian prospector Gabriel Read found gold in a creek bed close to the Tuapeka River in Otago. Read was a grizzled veteran of the Californian and Australian goldfields but was still moved by his find, writing of "gold shining like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night". Read christened the area 'Gabriel’s Gully', but as we can see from this 1862 photo, he was soon sharing the area with thousands of other prospectors.

1861-64: Otago Gold Rush, New Zealand

The 1860s saw Otago earn more than two and a half times as much from gold as it did from wool – formerly the staple of the local economy. Annual production of gold peaked at 17,400kg (38,360lbs) in 1863, as did the goldfield’s population, with 22,000 prospectors calling it home. Despite the introduction of elaborate water sluicing technology in1862 (pictured) the alluvial deposits were soon exhausted. Digging continued into the 1870s, but by 1864 the region's 'rushes' were already over.

1885-1897: Western Australia Gold Rush, Australia

The discovery of gold in Halls Creek in northern Western Australia in 1885 transformed the fortunes of Australia’s largest and most inhospitable state, and threw a lifeline to its tiny European population. Soon gold was found in other parts of the state, partly facilitated by the 300-or-so camels brought to the state by two Afghan brothers, Faiz and Tagh Mahomet. The camels could survive for days without water, allowing prospectors like A P Brophy (pictured here in 1895) to venture further and deeper into the Western Australian hinterland.

1885-1897: Western Australia Gold Rush, Australia

The yield at Halls Creek was small and the gold rush there quickly petered out. There were other finds in Yilgarn and Murchison but it wasn’t until gold was discovered 970 miles (1,560km) south in Coolgardie in 1892 that gold fever really took hold. Arthur Bayley and William Ford found a rich quartz gold seam in the September of that year, sparking a rush that saw this tiny waterhole east of Perth grow into the third largest town in the state, with 25,000 residents and 700 mining companies.

1885-1897: Western Australia Gold Rush, Australia

Coolgardie was also the scene of one of the most notorious incidents in the history of Australian gold mining. In July 1895 hundreds of prospectors stocked up on tools and provisions purchased at exorbitant 'rush' prices and hurtled 73 miles (117km) south to Lake Cowan. A man called McCann had led locals to incorrectly believe there was gold there, and when the angry miners returned to Coolgardie they were out for his blood. He was put into protective custody so the miners (pictured) burned an effigy of him outside the post office instead.

1886-1899: Witwatersrand Gold Rush, South Africa

In 1886 gold fever came to South Africa when a 40-mile-wide (60 km) belt of gold-bearing reefs was discovered underneath what would soon become Johannesburg. This 1886 image shows Ferreira's Gold Mine – the oldest part of Johannesburg, where gold diggers first settled. News of the find quickly spread and soon miners from all over the world were descending on this barren corner of the Transvaal. By 1899 the mines here were producing almost 30% of the world’s gold, making it the richest goldfield on the planet.

1886-1899: Witwatersrand Gold Rush, South Africa

The goldfield was certainly rich, but it was also technologically challenging. The ore ran extremely deep and required vast quantities of capital, technology and labour to extract. At their height the mines employed more than 100,000 people, most of them Black migrant workers. The mining companies colluded to keep labour costs down, and paid Black workers in particular a paltry wage. As we can see from this photo from the late 1800s, Black labourers worked alongside white miners, but earned only one ninth of their pay by the century's end.

1886-1899: Witwatersrand Gold Rush, South Africa

The discovery of gold in 1886 transformed the Transvaal, and within ten years Johannesburg was a bustling city of 100,000 people. What had once been a struggling republic run by the Boers (the descendants of Dutch-speaking settlers) was now a potential threat to British supremacy in South Africa. Here we see General Piet Joubert, the Boer general who helped defeat the British when they tried to annex the Transvaal in the ill-fated Jameson Raid in 1896. This led to the Boer War in 1899 after which the Transvaal – and the mines – finally fell under British control.

1896-1899: Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, Canada

The Klondike Gold Rush in Canada’s northern Yukon region is often referred to as 'the last great gold rush'. The precious metal was discovered in Rabbit Creek in 1896, but the region's remoteness meant that it initially remained a local affair. Then in July 1897 two ships laden with two tonnes of Klondike gold steamed into Seattle harbour and the fuse was lit. The headline in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer screamed "GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!" and the stampede for a passage north (pictured) began. Even Seattle’s mayor, William D Wood, quit his job to seek his fortune in the Yukon.

1896-1899: Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, Canada

Around 100,000 'stampeders' eventually set out for the Klondike, most of them woefully unprepared for life in the subarctic or the Herculean task of getting there. The journey included crossing the Chilkoot Pass (pictured), a 32-mile (51km) path that was too steep for pack animals and was often covered in snow. The Canadian government insisted that each stampeder bring at least a year’s supplies with them – roughly one tonne of goods per person – so it took more than one trip. Unsurprisingly, only 30,000 stampeders ever made it all the way to the Klondike.

1896-1899: Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, Canada

It didn’t get much better once the prospectors reached the Yukon. First, they faced the "petty tyranny" of Canadian officials who limited the size of mining claims and instituted a 10% tax on any gold found. Then they discovered that their allotted stretches of land were often moss-covered, mosquito-bitten, frozen wildernesses. Temperatures of -50°F (-46°C) were not unheard of in winter, forcing miners to thaw the ground with steam before they could begin prospecting (pictured in 1898).

1896-1899: Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, Canada

Dawson was the closest town to the goldfields and quickly transformed from a frozen backwater into one of the most populous cities in Canada. It was fancifully called 'the Paris of the North', but in reality was a muddy, ramshackle town full of saloons, gambling dens and a street of prostitutes known as 'Paradise Alley'. Those who did find gold often squandered their wealth as quickly as they'd mined it. One story holds that a miner named 'Swiftwater' Bill Gates offered a dancehall girl her weight in gold in exchange for her hand in marriage. She declined.

1896-1899: Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, Canada

Here we see a man at a store in Dawson paying with gold dust, his resigned expression typical of the Klondike's miners. By 1899 the modern equivalent of some $1 billion (£0.78bn) in gold had been removed from the area, yet most stampeders went home with almost nothing. As usual it was the merchants, shopkeepers, bar owners and brothel keepers who made the real money, a trend that continued into the 20th century when gold was found in other parts of North America and Africa.