Incredible Dark Age discoveries

Shedding light on the Dark Ages

We can blame 14th-century scholar Petrarch for believing the 'Dark Ages' were a time of primitive living. For centuries afterwards, historians repeated his idea that the early medieval period – roughly AD 400 to 1100 – was a dismal era when Europeans forgot the great achievements of classical antiquity in Greece, Rome, Persia and beyond. But many archaeological discoveries found in the centuries since suggest that the Dark Ages weren’t so bleak after all.

Click through this gallery to explore the surprisingly advanced civilisations of the not-so Dark Ages...

Prince of Prittlewell, c.AD 580

.jpg)

Archaeologists working on a road-widening scheme in Essex, England made a stunning discovery in 2003 – an underground burial chamber so stuffed with valuable objects that its inhabitant was nicknamed 'the King of Bling'. The artefacts in the late 6th/early 7th century tomb, including this drinking vessel with a gold neck, are now on display at Southend Central Museum.

They suggest that southeast England was part of a sprawling trade network; also found were gold coins from France, a flagon (jug) from Syria and garnets from Asia. Experts think the chamber was dug for Seaxa, the brother of King Saeberht of Essex – notable for being the first East Saxon king to convert to Christianity.

Aberlemno sculptured stones, AD 500-800

The small village of Aberlemno in eastern Scotland has four standing stones, their swirling artwork dating to when Christianity and paganism coexisted in the Pictish north of Britain. Contradicting the notion that Scotland's tribes were backwards compared to their Romanised southern neighbours, these stones are beautifully carved, especially the one bearing a Christian cross surrounded by serpents and horses on one side.

The reverse side bears a vivid depiction of a conflict thought to be the Battle of Nechtansmere, a nearby battle fought by the Picts and Northumbrians in AD 685. Unfortunately one of the stones was damaged in early 2025 after being blown over by a storm.

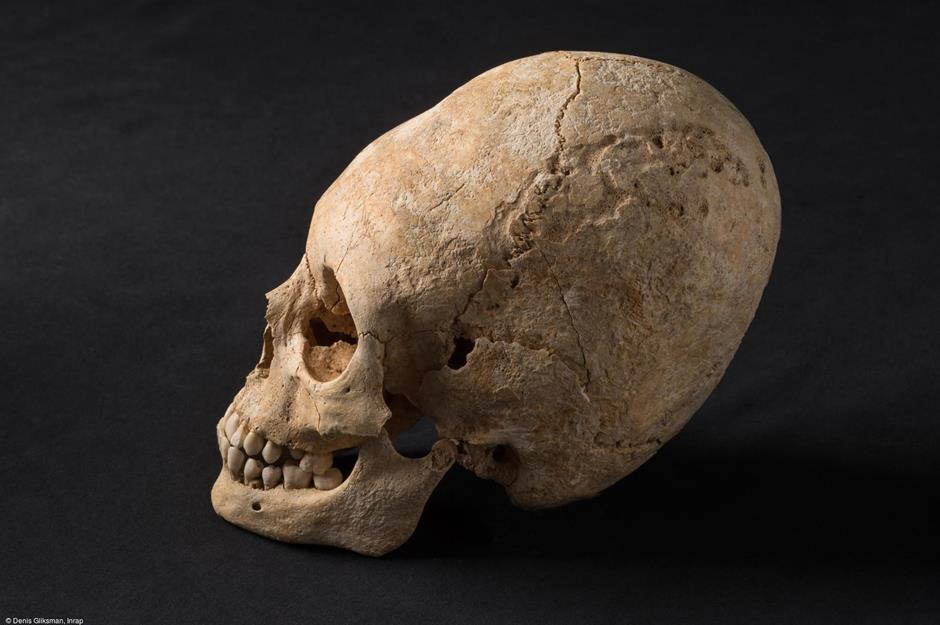

Obernai Skull, c.AD 400

A necropolis discovered in Alsace, France in 2013 contained burials spanning 7,000 years, but one Dark Age skull was of particular interest to researchers. The female skull (pictured) is deformed with an elongated, flattened forehead – achieved deliberately by tight binding during childhood.

Her body, meanwhile, was surrounded by a rich array of grave goods, including a silver mirror and glass beads. It suggests that Dark Age France had a sharp social hierarchy where the rich went to great lengths to make themselves stand out.

Chedworth Mosaic, c.AD 450

The beginning of the Dark Ages in Britain is traditionally dated to the last Roman garrisons sailing away around AD 410. But archaeologists investigating the Roman villa at Chedworth, Gloucestershire in 2020 realised that a fancy mosaic floor found in the villa's summer dining room was actually laid decades after the Romans left, when Britons were supposedly abandoning Roman life in favour of subsistence farming.

The intricate design suggests that Roman influence wasn't quite so quick to disintegrate in early medieval Britain: its aristocracy were keen to maintain a rich and sophisticated lifestyle years after the Dark Ages had supposedly begun.

Oseberg Ship Burial, AD 834

This impressive Viking ship burial, found at Oseberg in Norway in 1904, had two surprising bodies interred in it: two women of high status, one in her fifties, the other in her eighties. The two women were found in a bed made of linen and surrounded by luxurious items – from decorated sleighs to combs – but precisely who they were is a mystery.

Still, the ship in which they were buried is a neat example of the Viking aptitude for both shipbuilding and aesthetics. It had room for 30 oars and was adorned with complex and elegant carvings. In 2025, the ship was delicately moved to a new location in the revamped Museum of the Viking Age, which is set to open to the public in 2027.

Staffordshire Hoard, 7th century

There are few finer examples of Dark Age craftsmanship than the 3,500 items of the Staffordshire Hoard, found in 2009 by a metal detectorist in an otherwise anonymous field in the English West Midlands.

The incredibly detailed gold, silver and garnet jewellery proves that Anglo-Saxon goldsmiths were able to use metalwork techniques previously thought to be unknown to them, and some historians have hailed the hoard as the most impressive collection of early medieval artefacts ever found. The precious finds are now housed in museums in Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent.

Wendover Cemetery, 5th-6th centuries

In 2021, archaeologists digging ahead of HS2 – a new high-speed railway line – in Buckinghamshire, England, uncovered an Anglo-Saxon cemetery with 141 burials. The grave goods buried with the dead included many brooches (usually two on the collarbone, indicating they had held up cloaks), over 2,000 beads and 40 buckles.

There was even a personal hygiene kit complete with ear wax remover and tweezers. Contrary to popular depictions of Dark Age Britons as unwashed and dishevelled, Wendover’s Dark Age residents must have really cared about how they looked.

Maschen Disc Brooch, 9th century

The Dark Ages saw the conversion of northern Europe to Christianity, and the Maschen disc brooch – uncovered in a cemetery in Lower Saxony, Germany – is a great example of pagan practices blending with Christian ones. Some old rituals were hard to break, like the tradition of placing grave goods with people who were buried.

But the Maschen brooch features an unidentified saint (possibly Jesus) with a halo, a clue that the woman in the grave was a Christian. Plus, the use of enamel and copper for decoration suggests she had expensive – and fashionable – tastes. See the brooch for yourself in the Hamburg Archaeological Museum.

Anchor Church caves, 9th century

When King Eardwulf was deposed from the throne of Northumbria in AD 808, he was sent into exile and lived as a hermit in a man-made cave now situated near the village of Ingleby in Derbyshire, England. But the former king, believed by some to be Saint Hardulph, had a surprisingly comfortable existence.

His cave had interconnected rooms, a chapel and doorways and windows carefully carved in the style of Saxon architecture – probably forming the oldest intact domestic interior in Britain.

Book of Kells, 9th century

The Dark Ages were supposedly a time when ancient knowledge was lost due to a lack of literacy and effective record-keeping. But the Book of Kells, produced by monks in the British Isles sometime around AD 800, shows that skill with the quill was never really lost.

The illustrated manuscript of the four Gospels of the New Testament is extravagantly decorated with golden borders, Christian symbolism and more abstract insular art. No one knows precisely when or where it was made, and it's been variously claimed by England, Scotland and Ireland. The Book of Kells is now on display at Trinity College, Dublin, alongside other illustrated manuscripts.

Offa’s Dyke, late 8th century

Named after the King of Mercia who is traditionally thought to have ordered its construction, Offa’s Dyke is a bank and ditch constructed to protect Mercia’s eastern border with what is now Wales. The sheer scale of the early medieval earthwork is breathtaking.

It stretches over 150 miles (241km) and building it must have been a supreme logistical challenge – the kind of project that requires a powerful and complex system of governance that was once thought beyond the capabilities of Dark Age Britain.

Gilling Sword, late 9th century

Nine-year-old Gary Fridd must have given his parents quite a shock when he showed them what he found while playing in an English stream in 1976: a 33-inch (84cm) sword pulled from the riverbank. It’s thought to be an Anglo-Saxon weapon, and, although it has a beautifully-decorated hilt remarkable for the period, the sword is predominantly a functional object.

It may even have been carried into battle against the Vikings, who ravaged North Yorkshire around the time it was made. Defeated warriors often saw their weapons tossed into nearby rivers.

Gortnacrannagh Idol, late 5th century

Roadbuilders digging foundations across the boggy County Roscommon countryside in the west of Ireland made a surprising discovery in the summer of 2021: an eight-foot-tall (2.5m), 1,600-year-old sculpture carved from a single oak trunk.

The carved human figure, which predates the Christianisation of Ireland, sheds a rare spotlight on how complex early medieval worship was. It was probably deliberately dumped as part of a ritual, as the bogs were believed to be mystical places where the living could communicate with the dead. A full-size replica of the object is on display at the Rathcroghan Visitor Centre.

Coppergate Helmet, 8th century

When the bucket of a mechanical digger struck something hard under the streets of York, England in 1982, its operator thankfully stopped to check what the obstruction was. He had found the Coppergate Helmet, the best-preserved Anglo-Saxon helmet found in Britain. The item illustrates the skill and thoughtfulness of 8th-century weaponsmiths.

The original helmet is now held by the Yorkshire Museum, while the excavations that led to its discovery are covered in detail in the fun galleries at the Jorvik Viking Centre.

Galloway Hoard, c.AD 900

Who exactly buried more than one hundred precious objects near Balmaghie, Scotland is unclear, as this area was home to both Anglo-Saxons and Vikings during the Dark Ages. But we do know that the treasures originated from across Europe and even Asia, suggesting that medieval Galloway had trade links further afield than once thought.

The valuable gold, silver, glass and crystal artefacts, including the silver bracelet in this image, are now cared for by National Museums Scotland. In early 2025 an inscription on a silver arm ring was deciphered and translated as "this is the community's wealth", implying communal ownership of the hoard's riches.

The Birka textiles, c.AD 750

A set of entrepreneurial Vikings established the Birka trading post on a Swedish island, about 19 miles (30km) from Stockholm, which flourished for two centuries. Cargo came from distant lands, and perhaps the most impressive finds are textiles made from silk imported from the Byzantine Empire, the Middle East and China.

They indicate that, far from being insular and restricted to a small and chilly corner of western Europe, Viking trade contacts in the Dark Ages stretched to the other side of the known world. Birka is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and its stunning finds are displayed at the Birka Viking Museum.

Mästermyr Chest, c.10th century

When a Swedish farmer found a wooden chest in the drained wetlands of Mästermyr in 1936, archaeologists got a rare glimpse into the advanced techniques used by Viking craftsmen. Inside the chest were over 200 tools used by a carpenter and metalworker, many of which would look familiar to modern eyes.

Based on the finds, archaeologists deduced the craftsman it belonged to had some knowledge of locksmithing, coppersmithing and coopering. The owner of the Mästermyr Chest was a skilled artisan, not a mere Dark Age handyman.

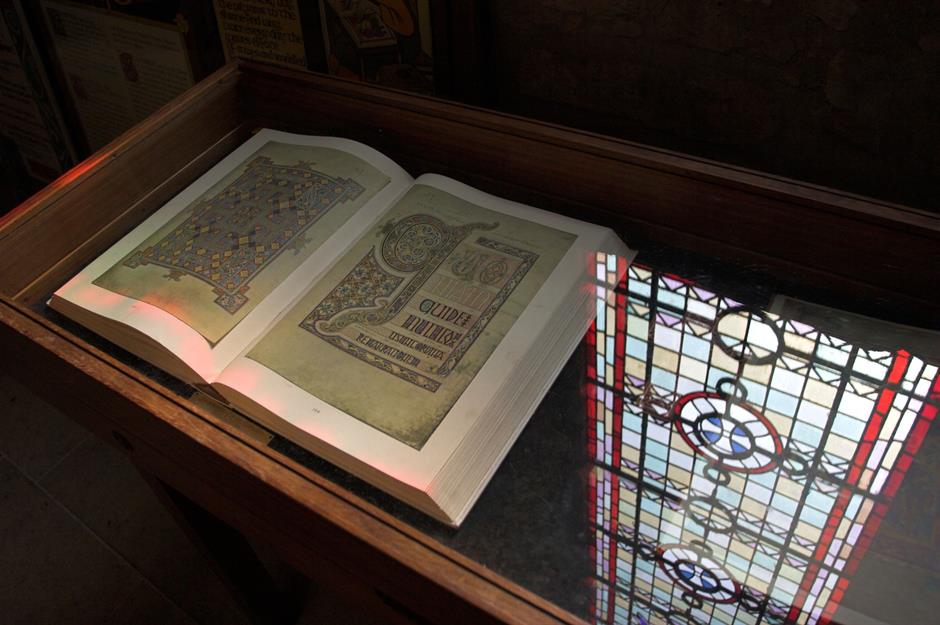

Lindisfarne Gospels, c.AD 715

The church was an important repository of knowledge in the Dark Ages, with monks creating illuminated manuscripts of both religious and secular texts. One of the most spectacular texts surviving from Anglo-Saxon England was produced at Lindisfarne, an island monastery off the coast of Northumberland.

Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, spent years copying the four Gospels and illustrating the pages with colourful decoration, some of which resembles the highly elaborate religious art of Byzantium. The manuscript is now in the care of the British Library, but a facsimile copy is displayed on Lindisfarne.

Alfred Jewel, late 9th century

Aside from tales about the absent-minded king burning cakes, Alfred the Great is famous for his love of books – far from the unenlightened monarchs said to exist during the Dark Ages. So it comes as no surprise that this exquisite piece of jewellery is thought to be the decorated handle of a pointer used for following words when reading.

The tear-shaped jewel, made from enamel and quartz encased in gold, was discovered in Somerset, England in 1693. Its inscription reads "Alfred ordered me to be made", a charming personal touch. The Alfred Jewel is now one of the most popular exhibits at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Lindholm Høje, 5th century

The expansive burial ground in the Lindholm Hills overlooking modern Aalborg in North Jutland, Denmark, was in use throughout the Dark Ages – firstly by the Germanic Iron Age inhabitants of the region, then by their Viking successors. Archaeologists have excavated 682 burials, 150 stone ships and a small village with Viking longhouses where the cemetery’s interred once lived and thrived.

These finds provide a wealth of information about north Denmark in the Dark Ages – coins from as far away as Arabia suggest it was a trading power. Want to see it for yourself? A museum explores the enthralling lives and deaths of the inhabitants of Lindholm Høje.

Hiddensee Treasure, 10th century

Harald Bluetooth, King of Denmark and Norway in the 10th century, was born a pagan but died a Christian. He helped to spread the new religion throughout Scandinavia. But a stash of treasure found on the Baltic island of Hiddensee in the late 19th century suggests he may have hedged his bets.

Among the 16 gold pendants are both Thor’s hammer Mjölnir and a Christian cross, so Harald may have harboured some affection for his old beliefs – an intriguing example of Dark Age duplicity. The gorgeous golden items also include a brooch and neck ring, and are now on display in the Stralsund Museum in Germany.

Sutton Hoo, c.AD 624

Perhaps the most famous Dark Age discovery of all, the awe-inspiring ship burial of King Raedwald of East Anglia at Sutton Hoo in England was first excavated in 1938. The scale of the royal internment illustrates the immense authority and wealth of Anglo-Saxon monarchs, as no simple chieftain could have managed the construction of such an impressive cemetery.

If any one discovery shows the Dark Ages in a new light, this is it. Visit the British Museum and the on-site museum at Sutton Hoo to view the beauty and craftsmanship of Raedwald’s many grave goods, including the famous helmet (pictured).

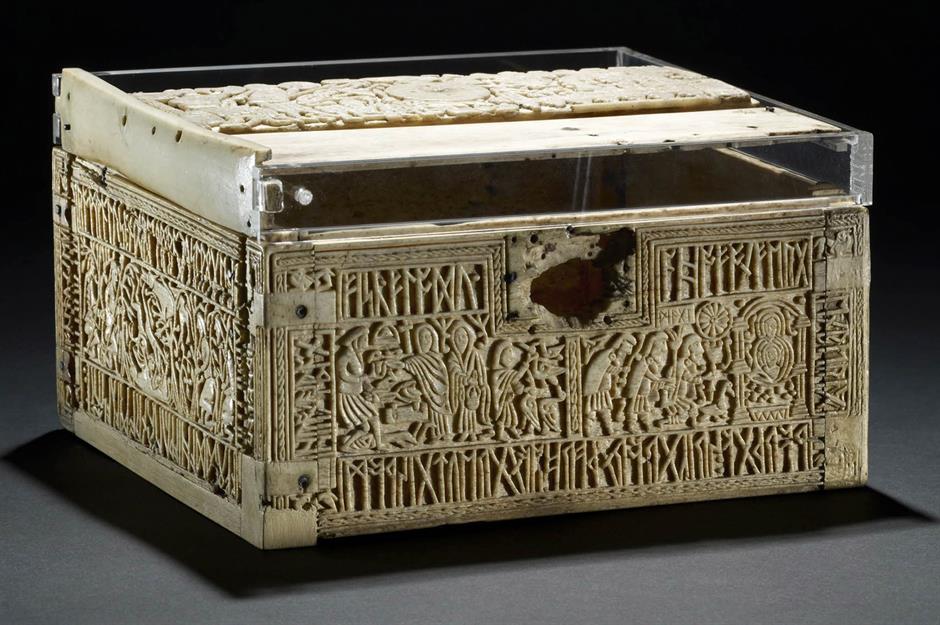

Franks Casket, early 8th century

The sculptor of the Anglo-Saxon Franks Casket was a man with diverse interests. The decorations, carved into the small whale-bone box with a knife, include a Christian image (the adoration of the Magi, or Three Kings), Roman history (the capture of Jerusalem by Titus in AD 70), Germanic mythology (Wayland the Smith enslaved by a king) and Greek legend (Achilles).

Probably made for a monastery, the box, which is housed in the British Museum, is a rare insight into the eclectic narratives from around Europe that were important in Anglo-Saxon England.

Lewis Chessmen, 12th century

It wasn’t all work, work, work in the Dark Ages. A stash of 78 chess pieces found on the Isle of Lewis in 1831 shows that early medieval Scots also enjoyed a little gaming. The intricately carved pieces are made of walrus ivory and sperm whale tooth, costly and rare materials obtained in Greenland by the Vikings (who occupied much of Scotland at the time).

The game must have been an expensive luxury for its owner – probably a local noble or wealthy merchant. The pieces are now split between the British Museum in London and the National Museum of Scotland.

Now discover the ancient finds that literally changed history...

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature