Incredible recent North American archaeological discoveries

North America unearthed

The thrill of archaeology comes from not knowing what the next shovel of soil will uncover, and over the past few years delighted archaeologists have reported stunning discoveries across North America. Some were found by experts applying new methods to old finds, others were the products of long-planned and careful excavations, and a few were the result of pure luck.

From fossilised footprints to barnacle-encrusted wrecks, click through this gallery to learn about the most important archaeological finds in North America since 2020...

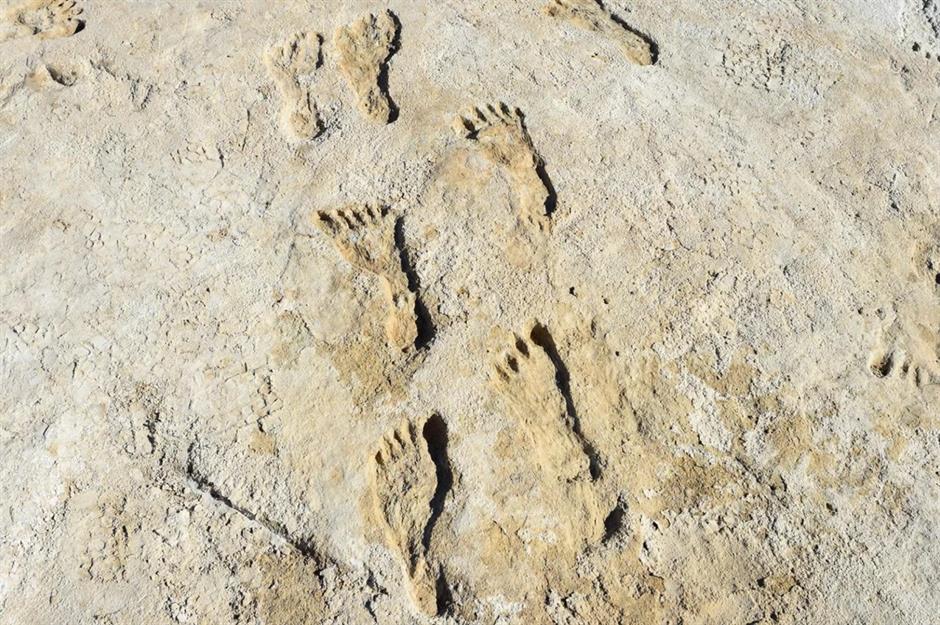

Fossilised footprints, White Sands National Park, New Mexico, USA

Experts have been aware of ancient footprints at White Sands since the turn of the 20th century, but in 2021 scientists announced that seeds found within the footprints push back their date of origin to 21,000 BC, which would make them the oldest human footprints ever found. Not everyone agrees – some think the dating methods are flawed – but nobody doubts that the prints were left by extremely ancient prehistoric people, mostly children and teenagers. Their feet left evidence that would cause archaeologists to argue thousands of years later.

Mayan neighbourhood, Tikal, Peten, Guatemala

When archaeologists examining laser scans of the region around the massive Mayan city of Tikal looked in more detail at an area of 'natural' hills, they made a remarkable discovery: the outline of a previously unknown neighbourhood of the city. When they mapped the neighbourhood in detail, they realised that the structures were close copies of the citadel at the ancient city of Teotihuacan, more than 600 miles (1,000km) away. The findings, published in 2021, offer proof of significant cultural interaction and exchange between the two cities.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

St Mary’s Fort, St Mary’s City, Maryland, USA

Colonial Maryland began in 1634 when British settlers began building a fort, but its exact location was lost to time since it was only used for around seven years. We now know that archaeologists were looking in the wrong place. Rather than sitting beside the river as expected, a geophysical survey directed archaeologists to a plateau around a thousand feet (300m) from the water. In 2021 wooden buildings and coins were revealed that proved the fort had finally been found.

Bonebed, Dinosaur Park, Maryland, USA

This part of Maryland has yielded evidence of prehistoric creatures for well over a century – that’s why it’s called Dinosaur Park – and new excavations in spring 2023 revealed a brand-new 'bonebed', a geological layer containing multiple dino species. The best find was a three-foot-long (1m) shinbone thought to belong to Acrocanthosaurus, a giant carnivore a little bit like the T-rex. "This is something palaeontologists pray for", said programme coordinator JP Hodnett.

La Union, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico

A cruel episode in Mexican history was discovered in the sediment off the country's north coast in 2020, when maritime archaeologists confirmed that a wrecked paddle steamer was the notorious La Union – a slave ship that transported dozens of Mayan captives to Cuba’s brutal sugarcane plantations every month. Its voyages came to an end in 1861, when its boilers exploded and the ship went down. Nobody knows how many Mayan slaves drowned that day, since they were listed as cargo rather than as passengers.

Dyar Mound, Lake Oconee, Georgia, USA

Dyar Mound was submerged under a reservoir built to serve Georgia in the 1970s, but, before the water covered it, archaeologists concluded that it had been abandoned in the 1540s after diseases brought by Spanish settlers ravaged the region. In 2020, archaeologists re-examined charcoal from the mound and concluded that people carried out rites on it up to 150 years after the arrival of the Spanish, meaning that the Indigenous Mississippian culture did not collapse quite as suddenly as previously thought.

Chinatown pigs, Los Angeles, California, USA

In 2022, archaeologists revisited pig bones pulled from the remains of the city’s original Chinatown. Using new scientific techniques to examine plaque on the teeth, they discovered that the pigs had eaten rice husks and leaves but not corn, indicating that the animals were raised locally and not on rural farms. Now, historians are using the evidence to track a previously unknown industry – backyard pig farming, mostly by Chinese migrant families contending with discrimination – and its impact on fast-growing LA at the turn of the 20th century.

K'awiil sculpture, Campeche, Mexico

In 2023, archaeologists clearing a path for the Maya Train project in the Yucatan Peninsula announced they’d made the exciting discovery of a rare statue of the Mayan god K'awiil. Experts identified the deity by his long, upturned snout and bulbous eyes. Although K'awiil has been depicted in paintings and reliefs, only three other sculptures have been found before – all at Tikal in Guatemala – so this is the first time a K'awiil statue has been found in Mexican soil.

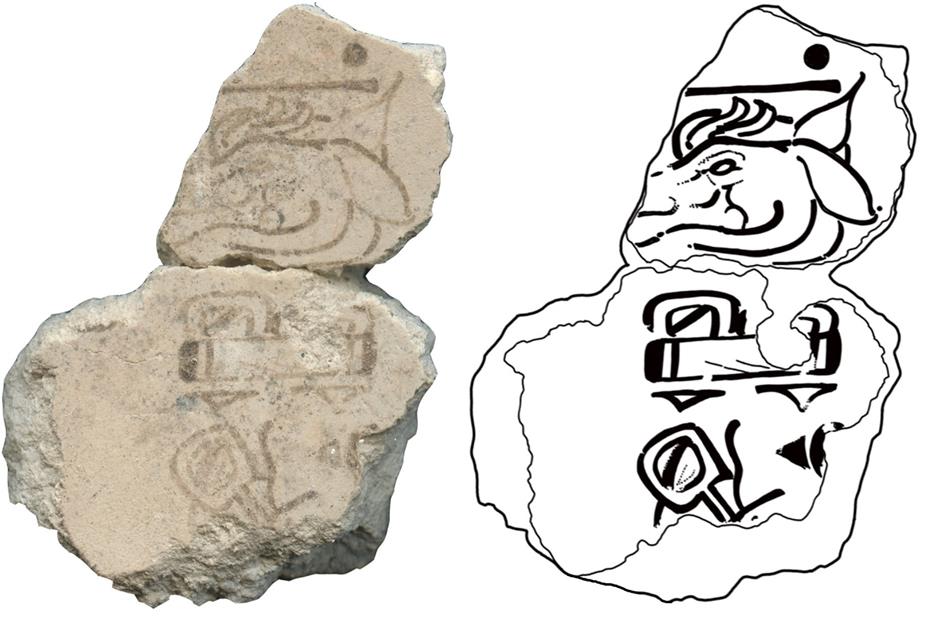

Maya calendar mural, San Bartolo, Peten, Guatemala

In 2022 archaeologists from the University of Texas and Skidmore College in New York studied murals recently discovered on a pyramid at the ancient Mayan city of San Bartolo. They identified one of the painted fragments as the Mayan date "7 Deer". It was painted around 250 BC, and represents the earliest known evidence of the Mayan calendar. Exactly why that date was recorded remains a mystery – perhaps it marked an important date in the construction of the pyramid, or an astronomical event.

Jaguar burial, Templo Mayor, Mexico City, Mexico

Aztec rulers venerated jaguars, and used the animal as a motif for the god Tezcatlipoca. One burial of a jaguar, found in the Templo Mayor in Mexico City in 2022, saw the big cat's skeleton entombed with a spear in its claw surrounded by 164 starfish. The starfish were well-preserved by the weight of the soil, and archaeologists could see that the chocolate chip starfish was probably chosen thanks to its orange colour and brown spots – not too dissimilar to a jaguar’s fur.

Dugout canoe, Lake Mendota, Wisconsin, USA

In May 2022, a scuba diving instructor stumbled across a carved tree trunk at the bottom of Lake Mendota. Thanks to a similar find the previous year, remarkably by the same person, maritime archaeologists quickly confirmed that it was a dugout canoe – a boat carved from a single piece of oak. They carefully raised it from the lake's sandy bottom and set about conserving the waterlogged wood. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the craft was built around 1000 BC, making it the oldest ever found in the Great Lakes region by more than 1,000 years.

Wood samples, L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

L'Anse aux Meadows isn’t a new archaeological site. Experts have dug there since the 1960s, unearthing evidence of a European Viking settlement in North America that predates Christopher Columbus by centuries. Recently, scientists used a new method for dating wood samples from the site to work out that the trees they came from were chopped down in 1021. Nobody knows exactly how long the Norse settlers stayed, but at least we now know precisely when some of the structures were built.

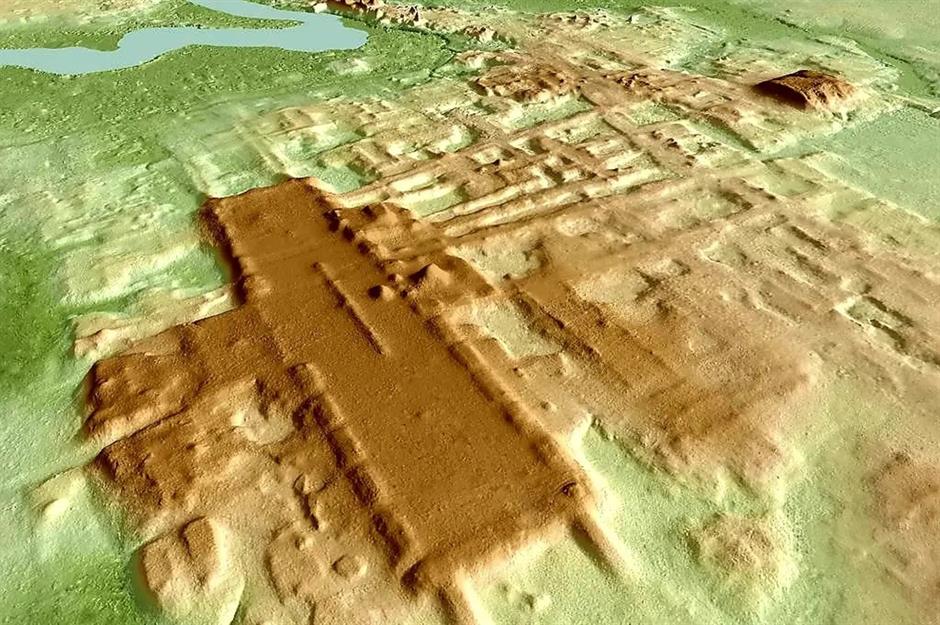

Aguada Fenix, Tabasco, Mexico

A team of archaeologists were flicking through laser scans from the southern state of Tabasco released by the Mexican government when a strange feature caught their eye. The team hurried to excavate the area, and their suspicions were confirmed. They’d found a mile-long (1.6km) ceremonial platform that rises 50 feet (15m) into the air, built by the Maya around 900 BC, making it the oldest Mayan structure on record. They named their discovery Aguada Fenix and announced it in June 2020.

Rock shelter remains, Bladen Nature Reserve, Toledo, Belize

Over the last few years archaeologists in Belize have dug up surprisingly well-preserved human skeletons from shallow graves underneath two rock shelters in Bladen Nature Reserve. A report published in 2022 revealed the surprising results of the skeletons' analysis – they’re up to 9,600 years old, and their genetic makeup suggests a mass migration from the south more than 5,600 years ago that preceded the advent of intensive maize farming in the region. Archaeologists think the remains may have been migrants whose agricultural techniques eventually helped new civilisations to flourish.

Ball game marker, Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico

The impressive Mayan city of Chichen Itza is one of the world's most recognisable tourist sites, but archaeologists continue to work there and regularly make stunning new discoveries. Recently, excavations revealed a heavy circular stone bearing two figures in elaborate headgear surrounded by Mayan writing. The carved stone is thought to have been a scoreboard for an ancient ritual ball game played on a court with a heavy rubber ball, which may have had similarities to modern racquetball.

These are the most intact archaeological discoveries ever unearthed

Stone projectiles, Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, USA

Did the ancient people who lived in Idaho 16,000 years ago have links to Japan? That’s the tantalising implication of a collection of 14 stone projectiles discovered by archaeologists at Cooper’s Ferry in 2022. It’s unclear whether the points were thrown away or cached for later use, but they resemble similarly shaped stone projectiles carved even longer ago across the Pacific on the island of Hokkaido in Japan. It's an intriguing idea, but some archaeologists remain unconvinced.

Animal teeth, Rimrock Draw Rockshelter, Oregon, USA

Archaeologists were stunned when they analysed fragments of camel teeth and stone tools marked with bison blood that they plucked from the soil at Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in Oregon. Radiocarbon dating of the enamel revealed that the teeth date back roughly 18,250 years, and the position of the stone tools in the sediment suggested that they might be even older. The team excitedly released their results in 2023, and started a debate as to whether the Rimrock Draw site is the oldest evidence of human occupation in western North America.

Petroglyphs, Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Saskatchewan, Canada

In December 2019 bison were reintroduced into Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Saskatchewan, almost 150 years after they were hunted to local extinction. Eight months later, the hooves of the heavy animals churned up the soil to reveal the top of a carved boulder. The bison had revealed four ancient rock carvings and a stone knife that may have been used to create the designs. One of the stones weighs 225kg (496lbs), and, given its method of discovery, is fittingly engraved with parallel lines that have been interpreted as bison ribs.

Spider monkey skeleton, Teotihuacan, Mexico State, Mexico

The highlands of Mexico State are a long way from the natural jungle habitat of the spider monkey – but that didn’t stop archaeologists finding a spider monkey skeleton buried in a rich neighbourhood of the ancient city state of Teotihuacan. They think the animal was an exotic gift from a Mayan emissary that was part of diplomacy between the city and the Mayan elite. The animal's death – probably from ritual sacrifice – occurred around 1,700 years ago.

Pecos River rock art, Mexico and Texas, USA

Historians have long been aware of ancient rock art and petroglyphs across the North American continent. Archaeologist Carolyn Boyd has made the study of the Pecos River Style in southwest Texas and northern Mexico her speciality, and in 2021 she co-authored a study suggesting that the style's dots and lines of red pigment are supposed to represent sound. According to the study, these 2,000-year-old speech bubbles "denote speech, breath and the soul". Some figures have delicate lines from their mouths as though whispering, while one has energetic zigzags as though shouting.

Horse tooth, Puerto Real, Haiti

Archaeologists weren’t particularly surprised to discover a fragment of horse tooth at an old Spanish colonial settlement in Haiti in 2022. But they were very surprised when genetic material from the tooth showed that the horse’s closest living relatives aren’t found in Spain, but on the island of Assateague off the east coast of the US, where feral horses have mysteriously roamed freely for centuries. This discovery would seem to support the theory that Spanish explorers were the source of the island's horses, who for whatever reason began new lives as wild animals on the island's beaches.

Slave tag, Charleston, South Carolina, USA

Evidence of South Carolina’s slaveholding past was unearthed when students from the College of Charleston helped to excavate part of their campus ahead of rebuilding works in 2021. They found a copper slave tag labelled '1853' – these tags were used to prove that an enslaved person was authorised to work for someone else besides their owner. Most likely the tag was worn by an enslaved person who was hired out to work in a kitchen that existed on the site in the mid-19th century.

Fire damage, Jamestown, Virginia, USA

In 2021 archaeologists in Jamestown in Virginia – the site of the first permanent British colony in North America – discovered a layer of charcoal and burned earth near where the parish church once stood, just below artefacts confidently dated to the 1670s. The findings confirm historical accounts from the era: that a blaze broke out in Jamestown in 1676 during a rebellion led by Nathaniel Bacon, the first major uprising in the British colonies a hundred years before the revolution. The rebels burned Jamestown's church to the ground, and this layer of ash and rubble is all that remains.

Young Woman of Amajac, Hidalgo Amajac, Veracruz, Mexico

Farmers in the Mexican town of Hidalgo Amajac started their new year with a surprise when they prepared a field for planting on 1 January 2021. They dug into the soil and found the statue of a woman – possibly a ruler, possibly a god – thought to be around 500 years old. Whoever she is, the Young Woman of Amajac was cleaned up and is now displayed in the town, while a replica was made and put up in Mexico City.

Human skeletons, Fortress of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, Canada

The 18th-century French fort at Louisbourg is perched precariously atop Rochefort Point and often endures vicious Atlantic weather. After Storm Fiona hit the area in September 2022, archaeologists found that the skeletal remains of two people had been exposed in the fortress burial ground, and were at risk of washing into the sea. They rushed to save the bodies from the waves and sent them for scientific analysis, though they’ll eventually be reburied in a safer part of the cemetery.

Burned barracks, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA

In the summer of 2023, archaeologists at Colonial Williamsburg unearthed a fascinating find: a barracks burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. The barracks was only used during the war – built in 1776-77 and razed in 1781 – which makes it a particularly intriguing time capsule. British General Cornwallis burned its buildings en route to his pivotal defeat at Yorktown, and key artefacts include gun hardware, lead shot that was chewed by bored soldiers and high-end ceramics. The discovery was announced in May 2024.

Gomolak Overlook archaeological site, Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, USA

In May 2023 an 8,200-year-old campsite was unearthed at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. Uncovered by two geomorphologists with the help of 49th Civil Engineer Squadron personnel, the prehistoric site had spent millennia buried beneath white sand dunes, and may have been used by some of New Mexico's earliest settlers. The site yielded a series of hearths, complete with charcoal remnants, and was named after JR Gomolak – Holloman's recently retired cultural resource manager. The discovery was announced in March 2024.

Dog bones, Jamestown, Virginia, USA

A 2024 study has made a gruesome claim about the early colonial settlement of Jamestown, Virginia – that starving colonists killed and ate local dogs. The study, published in the journal American Antiquity, found that unearthed dog bones bore cut marks that implied deliberate butchery, and that these dogs were at least partly related to those that roamed America before Europeans arrived. Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised: in 2013 archaeologists also discovered evidence of cannibalism at the settlement during the harsh winter of 1609-10.

Now uncover Europe's most important archaeological discoveries

Comments

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature