The surprising stories of the world’s best-known ruins – AFTER they fell out of use

Repurposed ruins

Among the world’s most popular tourist destinations are historic monuments and buildings that have stood for centuries, if not millennia. Visitors learn about their remarkable heydays, when they may have been used as temples, government buildings or military fortresses. But if they're still standing now then that raises the question: what's happened to them in the years since?

Click through this gallery to explore some of the world's most famous historic landmarks – and discover what happened to them after their heydays ended...

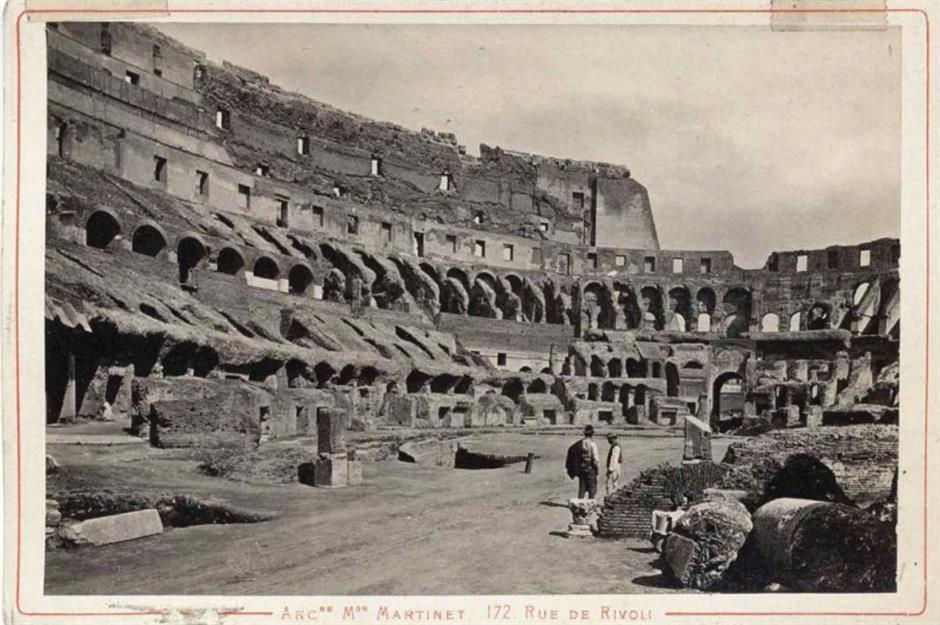

Colosseum, Italy

Also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, the Colosseum is perhaps the most iconic landmark surviving from ancient Rome – a multi-storey arena large enough for at least 50,000 spectators in its prime. When construction finished in AD 80, the Roman emperor Titus celebrated with a dedication ceremony and then 100 straight days of games. It was a bloody spectacle that set the tone for the next four centuries of gladiatorial bouts, animal hunts, battle reenactments and possibly even mock sea battles that required the floor of the Colosseum to be flooded.

Colosseum, Italy

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Colosseum’s grandeur gradually ebbed away. The arena was turned into housing, workshops and a cemetery – before two powerful Roman families tried to use it as a fortress. The building fell into disrepair, and in 1349 a massive earthquake caused a whole section of the outer wall to collapse. The site essentially then became a quarry as stones were plundered for building projects. Some of the Colosseum’s marble became part of another local landmark, St Peter’s Basilica.

Luxor Temple, Egypt

The Egyptian city of Luxor has been described as 'the world’s greatest open-air museum' thanks to two major ancient sites, Karnak and Luxor Temple. Built around 1400 BC, the latter grew into a vast temple complex on the banks of the Nile, added to and altered by pharaohs including Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II. Non-Egyptian rulers like Alexander the Great also left their mark. Also known as the Southern Sanctuary, Luxor was among the most important religious centres of the ancient Egyptian world.

Luxor Temple, Egypt

Over the millennia, parts of the Luxor complex were used for religious worship to gods that were not Egyptian, and the remnants of Christian churches can still be seen today. Among the most intriguing features is the Mosque of Abu Haggag, which was added in the 12th or 13th century. Much of the temple complex was buried when the mosque was built, and many of the ancient stones became its foundations. Excavations then revealed the ruins below, leaving the mosque – still in use today – perched on top.

Palace of Versailles, France

Few rulers epitomised absolute monarchy more than Louis XIV of France, who ruled for 72 years from 1643 to 1715, and nowhere encapsulated his power and excess more than the Palace of Versailles. He turned his father’s hunting lodge outside Paris into a gargantuan royal residence stretching out to the horizon. The most precious jewel in the Versailles crown was undoubtedly the Hall of Mirrors: a grand gallery 230 feet (70m) long with wide windows on one side and hundreds of mirrors on the other, causing every inch of the room to gleam.

Palace of Versailles, France

Versailles survived the French Revolution and was briefly used as a residence by Napoleon, but it would find a new role in the military and political worlds of the 19th and 20th centuries. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the German army occupied the palace and it was in the Hall of Mirrors that the German Empire was officially proclaimed. It was also there that the peace treaty, following months of negotiations in Paris, was signed to end the First World War.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

Masada, Israel

Masada is more than just a fortress on top of a plateau above the Judaean Desert. It is also seen as a symbol of Jewish resistance and freedom, as it was here that Jewish forces made their last stand against the Romans with a long and bloody siege in AD 73. The story goes that the defenders chose to take their own lives en masse rather than be captured – though some modern historians are sceptical. The assault ramp built by the victorious Romans can still be seen, as well as the remnants of the garrison they established.

Masada, Israel

Masada is best known for its monuments built by the King of Judea Herod the Great, who reigned from 37 to 4 BC, but a Byzantine church from the 5th and 6th centuries also stood on top of the cliffs. That was the last time the site was occupied. In the 20th century, Masada became a place of pilgrimage for the Jewish community, while today visitors can either make a tricky ascent on foot or take the much easier cable car to the top. There they can explore the remains of Herod’s palace, the Roman bathhouses and the Byzantine church.

Whitby Abbey, England, UK

The seaside town of Whitby in Yorkshire has long been recognised for its importance in the early chapters of Christianity in England. The monastery was built there in the 7th century and was a major religious centre for the Anglo-Saxons, becoming the setting for the great meeting, or synod, that decided the date of Easter. While Viking raids scared off the monks in the 9th century, a Benedictine abbey rose up on the same site in 1078, the ruins of which are what we see today.

Whitby Abbey, England, UK

In 1539, Whitby Abbey was closed during the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII and stripped of all its valuables. But its dramatic ruins would find a second life as a popular seaside attraction. Its atmospheric location high on the cliffs above the sea planted the abbey firmly in the Gothic imagination, and author Bram Stoker was inspired by his visit in 1890 to include it in his seminal novel, Dracula. The vampire, disguised as a dog, climbs up the town’s famous 199 steps that head towards the abbey.

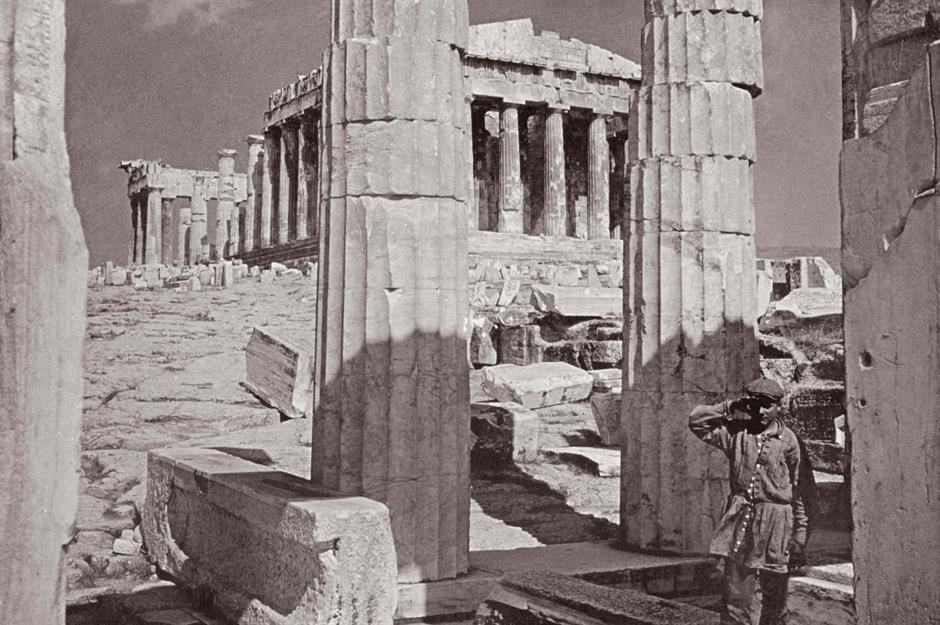

Brandenburg Gate, Germany

When the Prussian king Frederick William II commissioned the Brandenburg Gate in the 1780s, it was intended as a showpiece for a new-look Berlin filled with cultural monuments. It would be the entrance to a grand boulevard leading to the Prussian palace, a Neoclassical gateway 85 feet (26m) high, 213 feet (65m) wide and fronted by rows of Doric columns. It was inspired by the ancient Propylaea – the 2,400-year-old gates to the Acropolis in Athens. On top was added a statue of a quadriga (a chariot drawn by four horses).

Brandenburg Gate, Germany

The Brandenburg Gate was a useful propaganda symbol for the Nazis, but the structure suffered heavy damage during the Second World War and had to be restored. Then came the Cold War: in 1961, the German capital was divided by the Berlin Wall into the communist east and capitalist west. The gate, just inside the communist zone, came to represent the split. US President Ronald Reagan gave his famous "tear down this wall" speech in front of it in 1987. Two years later, the wall finally came down.

Parthenon, Greece

The unquestionable centrepiece of the Acropolis is the Parthenon – the ruins of a magnificent columned temple that has stood on the rocky outcrop above Athens since the 5th century BC. It served as a shrine to the goddess Athena, decorated with the finest sculptures and friezes, and the treasury of a powerful confederacy of Greek city states. It was built when the city of Athens was at its peak, under the direction of the great statesman Pericles, and has long been celebrated as ancient Greece's most iconic monument.

Parthenon, Greece

The Byzantine Empire turned the Parthenon into a Christian church in the 6th century, before the Ottoman Turks made it a mosque in the 15th. Disaster struck in 1687 when the Ottomans decided to use the ancient edifice as an ammunition store while Athens was under siege. A shell struck the building and a huge explosion blew the roof off and damaged the walls and columns. Much of the surviving art has since been removed, most infamously by the British nobleman Lord Elgin, who sold a large collection of sculptures to the British Museum. The so-called Elgin Marbles remain there to this day in spite of repeated calls for them to be returned to Greece.

Hagia Sophia, Turkey

Not only is the Hagia Sophia one of the world’s most beautiful buildings, it also symbolises 1,500 years of tumultuous religious and political history. What we see today is the third attempt at a Christian Greek Orthodox basilica. The first two burned down, leading Byzantine emperor Justinian I to construct this spectacular replacement, erected in just six years, between AD 532 and 537. It was an architectural wonder to last the ages, both as a church and as a coronation site for new emperors.

Hagia Sophia, Turkey

Following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1453, Hagia Sophia was turned into a mosque. Additions were made, including minarets and a mihrab (a niche in a wall pointing in the direction of Mecca). For centuries, the building combined iconography from both religions, from Christian mosaics to Islamic calligraphy. Then, in the 1930s, the first president of an independent Turkey transformed it into a museum. Its status remains controversial today: in 2020, the decision was made for Hagia Sophia to become a mosque once again.

These are the most incredible ancient discoveries uncovered recently

Old Sarum, England, UK

There’s not a huge amount to see now, but Old Sarum has been an Iron Age hillfort, a Roman settlement and a Saxon residence. That’s all before the Norman Conquest of 1066, which really put the hill on the map. At its height, it boasted a Norman castle, cathedral and town, and served as a religious and administrative hub. As time wore on Old Sarum fell out of favour thanks to tensions between the church and the garrison, and the difficulties of the exposed hilltop terrain. In the 13th century, the cathedral was moved to the nearby town of Salisbury.

Old Sarum, England, UK

As the importance of Old Sarum dwindled, the site took on a new and peculiar political role. It became a rotten borough: a particularly corrupt democratic quirk in which small areas with few voters, which could easily be controlled by the rich and powerful, had disproportionate representation in parliament. Old Sarum, despite being abandoned and having only a handful of residents, had two MPs. That was more than entire towns elsewhere in England, and this remained the case until major electoral reforms in 1832.

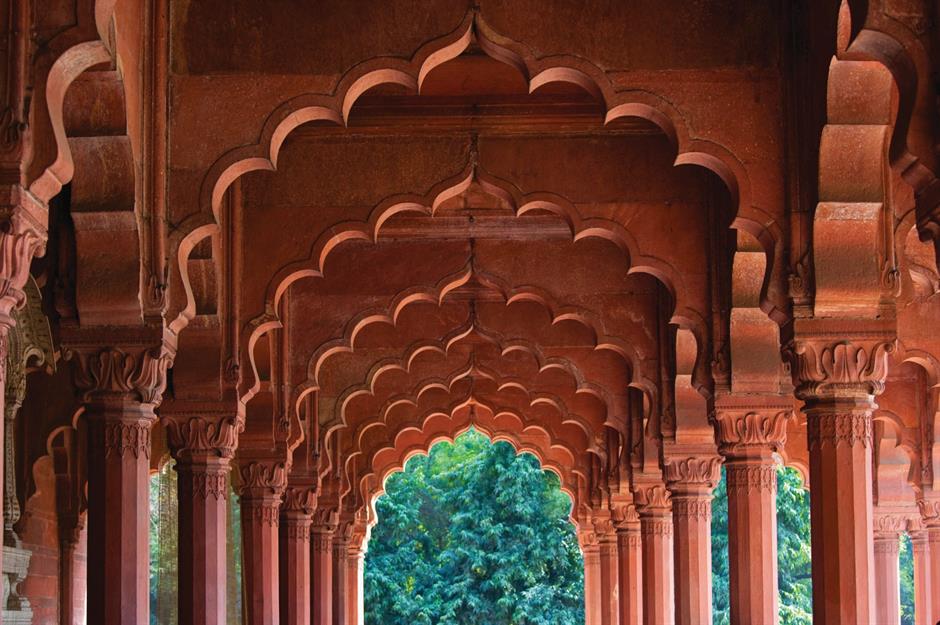

Red Fort, India

The name of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan is more often linked with another magnificent Indian building – a certain Taj Mahal – but the Red Fort in Old Delhi is an architectural masterpiece in its own right. Taking a decade to build in the mid-17th century, the fort gets its name from its red sandstone walls, which are 75 feet (23m) high and contain a fortress, palaces, halls, mosques, gardens and the Chhatta Chowk bazaar. Sadly, Shah Jahan never took up residence in the fort as his son turned on him and had him locked up.

Red Fort, India

In 1857, a mass rebellion against British rule in India broke out, and, while it ultimately failed, it sowed the seeds of independence. In the immediate aftermath of the mutiny the British plundered the Red Fort, demolishing a large proportion of its buildings and replacing them with stone barracks. The symbolism of the Red Fort was not lost, however. When independence came in 1947 Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru raised the national flag above the fort, and the act is repeated on Independence Day every year.

Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany

The picturesque Neuschwanstein Castle still looks like something out of a fairy tale. Rising from a rock ledge in the Bavarian Alps, the sprawling building was famously the inspiration for the castle at Disneyland. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig II, ordered its construction in 1868, not as a stronghold but as a royal residence and a celebration of Romanticism and the Neo-Gothic style. He would not see his grand vision realised, however, as it remained incomplete on his death in 1886.

Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany

Due to its secluded location, Neuschwanstein Castle did not hold much strategic value in the First or Second World Wars, so it mostly escaped damage. That said, it did find renewed purpose under the Nazis as a depot for plundered treasures and art. When the end of the war neared, the Germans considered blowing up the castle to prevent the enemy seizing this horde, but, thankfully, the men stationed there surrendered. Walt Disney visited Neuschwanstein in the 1950s, and it directly inspired the castle in Sleeping Beauty (1959).

Pyramids of Giza, Egypt

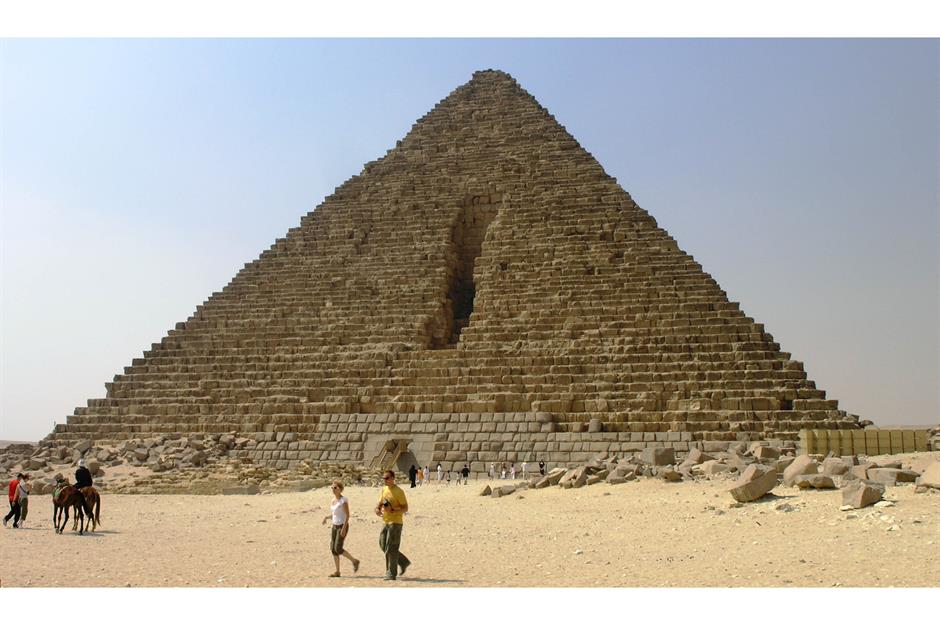

The only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing, the pyramids tell perhaps the longest tale of any major monument on Earth. Erected as tombs for the ancient Egyptian pharaohs Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, the three colossal stone structures have stood stoically in the desert for an astonishing 4,500 years. All three pyramids were looted of their riches by grave robbers during the reigns of later pharaohs, and they had long been ruins by the classical era. But they still mightily impressed Greek and Roman visitors – including Herodotus, often called the world's first historian.

Pyramids of Giza, Egypt

Arab forces conquered Egypt in AD 641, and, although early Muslim scholars were entranced by their scale, one 12th-century ruler attempted to tear the pyramids down. Sultan Al-Aziz Uthman's stonemasons spent eight months creating this small dent in the Menkaure pyramid before realising that giant piles of rock are not so easily destroyed. Napoleon won the Battle of the Pyramids within sight of the Great Pyramid in 1798, and the first archaeologists arrived in the early 19th century, doing irreparable damage to the monuments by blowing open the entrances with gunpowder.

Forbidden City, China

For around 500 years, the Forbidden City was the home of the emperors of China, a vast 178-acre complex in the heart of Beijing that also served as the centre of government. Inside are palaces, temples and gardens of varying sizes and opulence. The Forbidden City – so named since only a select group of people could enter, and even they were not permitted everywhere – first housed the imperial court in 1420, and did so until the final emperor, Puyi, left for good in 1924 after the Chinese Revolution.

Forbidden City, China

The year after the last emperor was forced to leave, the Forbidden City was turned into the Palace Museum and opened to the public. Today, it holds more than 1.8 million pieces of art in its collections, from paintings and sculptures to ceramics and rare documents. As one of China’s most popular tourist destinations, it welcomes approximately 16 million people every year to witness its architectural marvels, such as the Palace of Heavenly Purity and the Tiananmen Gate, which these days is always adorned with a portrait of Chairman Mao.

Alcatraz, California, USA

In 1849 the US government took control of an island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, where they erected California’s first lighthouse and then an army fortress. Today, Alcatraz Island is far more famous as one of the world’s most infamous prisons. Opened in 1934, the Rock was said to be impossible to escape from. Even if inmates got out of their cells and avoided being spotted by guards, their chances of swimming to shore in the strong, cold currents of the bay were next to zero.

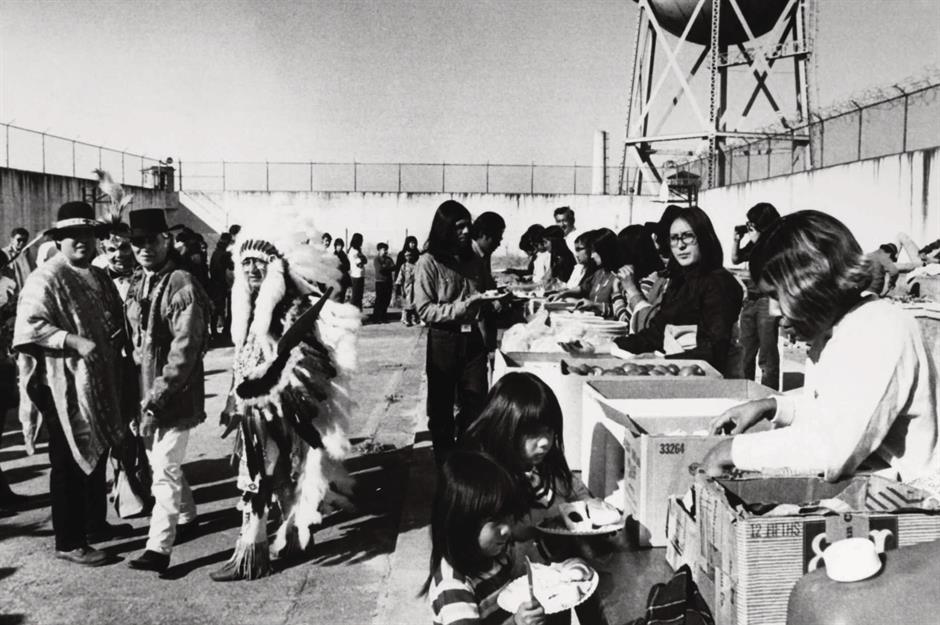

Alcatraz, California, USA

Alcatraz stopped being a prison in 1963 – having housed the likes of Al Capone and Machine Gun Kelly – but it found a new purpose as a place of protest. In 1969, Native American activists led by a Mohawk named Richard Oakes occupied the island in the name of 'Indians of All Tribes'. They cited a 19th-century treaty that granted unused federal land to Native Americans, but were forced from the island after 19 months, after which Alcatraz opened to the public. The water tower still bears this graffiti: "Peace and Freedom. Welcome. Home of the Free Indian Land."

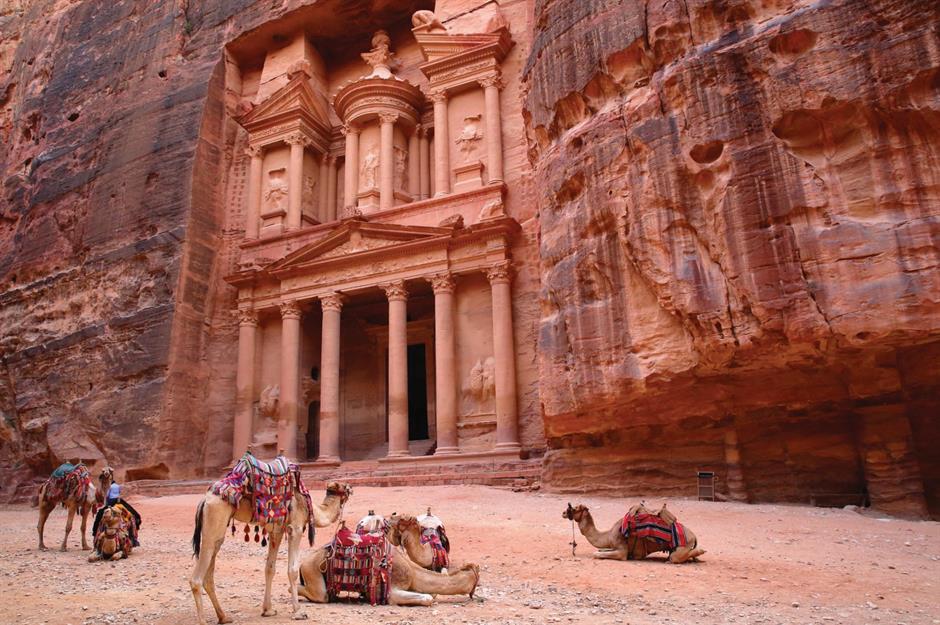

Petra, Jordan

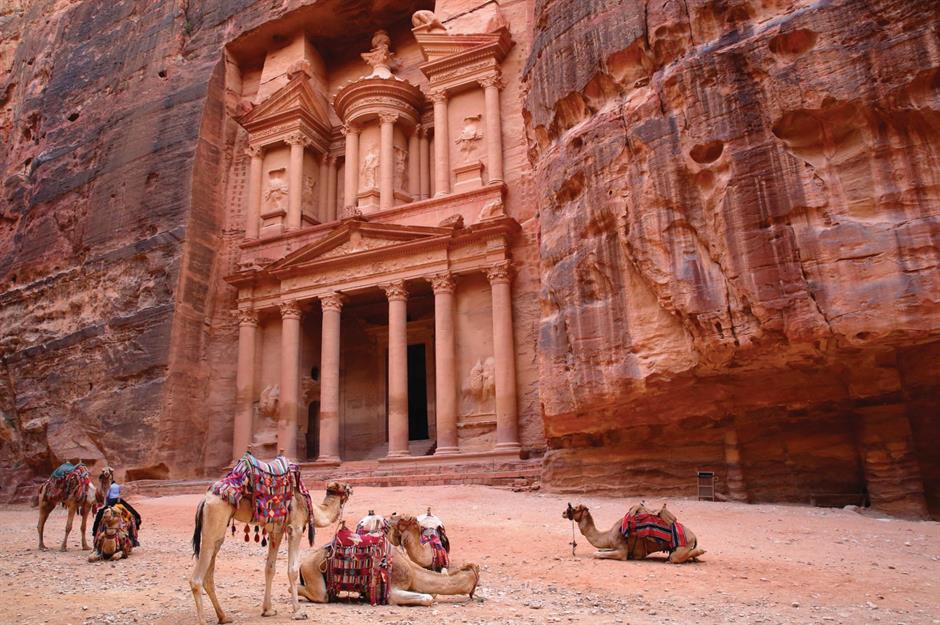

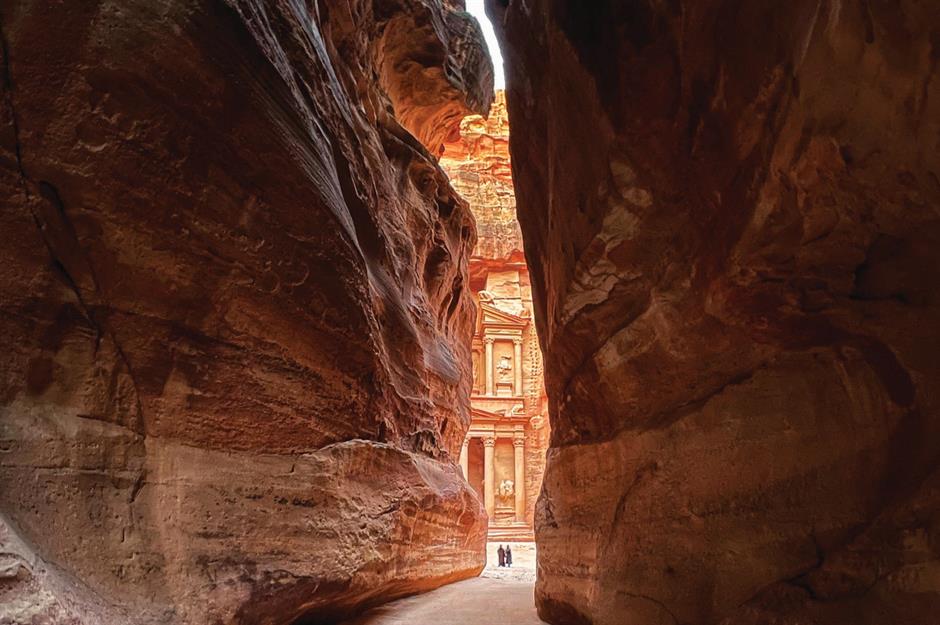

No trip to Jordan is complete without a lengthy visit to Petra. Once the capital of the Nabataeans, an ancient desert civilisation, Petra was carved out of the sandstone cliffs around the 4th century BC. Today visitors access the site via a narrow gorge in the mountains, making its instantly recognisable architecture even more dramatic. Petra is also celebrated for its sophisticated water management system, which supported a population of up to 30,000. The city was a vital crossroads for trade, linking Greece and Egypt to China and India.

Petra, Jordan

You can see from the city's architecture that numerous civilisations left their mark. The name 'Petra' is Greek, and the city fell into Roman, Byzantine and Crusader hands over the centuries too. Known as the Rose City for the gorgeous colour of its rock, Petra's best-known site is Al-Khazneh (The Treasury), a tomb fronted with a Greek-inspired facade. Many people will have first seen Petra in the 1989 smash hit Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade, in which the Treasury provides the setting for the finale in Indy’s quest for the Holy Grail.

Now marvel at these extraordinary photos showing what the world looked like in the 19th century

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature