Then and now: how climate change is affecting the world's famous rivers

Endangered rivers

The ongoing climate crisis is having a devastating impact on communities and ecosystems around the globe. This can be partially examined through our rivers, which for millennia have been the lifeblood of our planet. Rising water temperatures are killing the oxygen supplies of aquatic life and destroying water quality, while global warming has been directly linked to droughts and floods triggered by changes in our rivers’ flows – often at a deadly cost. Here, we reflect on how some of the world’s rivers have been altered over the years.

Click through the gallery for shocking then-and-now images of the world’s rivers affected by climate change…

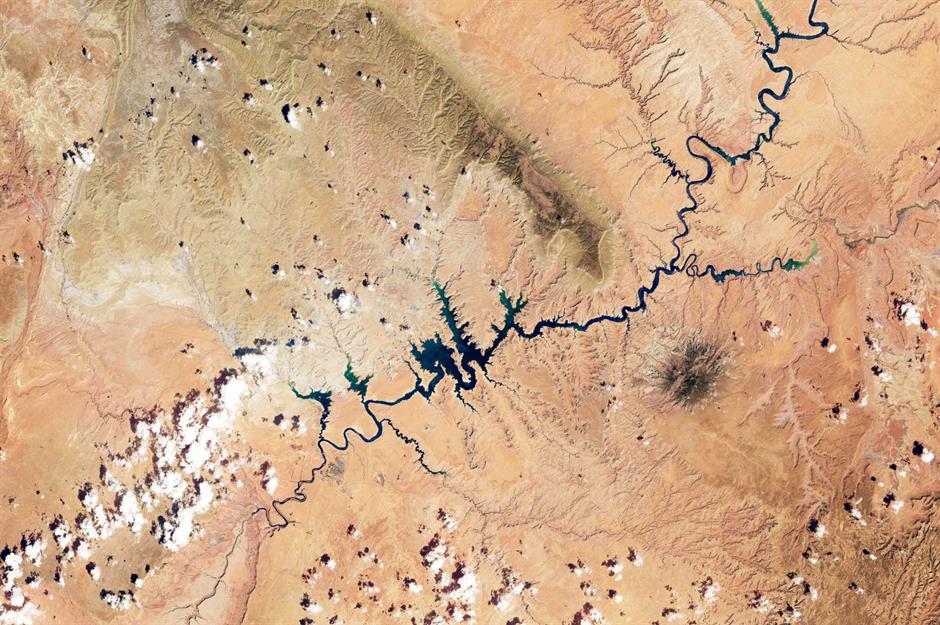

Then: Colorado River, USA

From its source in the Rocky Mountains to its mouth in the Gulf of California, the Colorado River is America’s fifth-longest river. Its drainage basin furnishes 40 million people with fresh water, encompassing parts of seven states, 29 tribal nations and a 17-mile (27km) stretch of the international boundary with Mexico. Often called the ‘Lifeline of the Southwest’, the river is crucially maintained by two of the biggest reservoirs in the US: Lake Mead and Lake Powell. It famously flows through the Grand Canyon and the meanders of Horseshoe Bend (pictured).

Now: Colorado River, USA

In the America’s Most Endangered Rivers report of 2023, the Colorado River came out on top for the second consecutive year. Impacted by a damaging combination of poor water management, over-exploitation and climate change, the river is drying up at its banks and drastically thinning out. Lake Mead has been shrinking since 2000 and even more rapidly so since 2020, while Lake Powell (pictured) dropped to historically low levels in February 2023. According to The Guardian, the Colorado River has lost 10 trillion gallons of water since the turn of the millennium, due to rising global temperatures exacerbated by the climate emergency.

Then: Yangtze River, China

The Yangtze River is China and Asia’s longest river, as well as the third-longest river in the world. It flows from the Plateau of Tibet to the South China Sea, spanning a length of 3,915 miles (6,300km) and traversing 19 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. The river’s sprawling basin is home to more than 400 million people, nearly a third of the whole national population. Many major cities are served by the Yangtze, including Shanghai, Wuhan and Chengdu. This photo of the river was taken in the city of Yichang in May 2006.

Now: Yangtze River, China

China’s most important river has been bearing the brunt of the climate crisis for years, with fluctuations in its flow resulting in both flooding and water scarcity. Things came to a head in 2022 when China declared a nationwide drought for the first time in nine years, which devastated vital hydropower supplies and dried up the Yangtze. As the river is fed by glaciers in the Himalayas, it is especially vulnerable to global warming: increased glacial melt leads to flooding, while long-term retreat could starve the river of its source. This image shows the Yangtze’s parched riverbed at Yichang in March 2023.

Then: Sutlej River, South Asia

Longest of the five principal tributaries of the Indus River that give the Punjab (meaning 'five rivers') region its name, the Sutlej River emerges from the Tibetan Himalayas before making its way through India and Pakistan. Fed by spring and summer snowmelt from the world’s tallest mountains, as well as the monsoon rains, the river has been known to experience significant flooding downstream during particularly heavy rains. The image here, captured by NASA Earth Observatory, shows a stretch of the Sutlej near Firozpur in northwest India early in the 2023 monsoon season on 16 June.

Now: Sutlej River, South Asia

But by 19 August 2023 (pictured), weeks of unrelenting downpours had flooded farmland and hundreds of villages in Punjab. The Sutlej spilled over its banks, with water levels at the Ganda Singh Wala village gauging station near Firozpur reported as 'exceptionally high'. It was later confirmed by one of Pakistan’s chief meteorologists that the river was at its highest in 35 years. While monsoons are crucial to the survival of nearly a quarter of the world’s population, global warming is making them stronger, more erratic and therefore more deadly. In 2022, extreme rains flooded almost a third of Pakistan and killed more than 1,000 people.

Then: Murray and Darling Rivers, Australia

The Murray is Australia’s longest river. It meets with the nation’s third-longest river, the Darling, to form an immense basin spanning about one seventh of Australia’s total area (about the size of France and Spain combined) and four different states, as well as the Australian Capital Territory. Climate change is not a new issue facing the Murray-Darling Basin: this aerial shot from 2006 coincides with the year that then-Australian prime minister John Howard called a water summit with reps from South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria to discuss its drought-stricken rivers.

Now: Murray and Darling Rivers, Australia

In 2021, researchers identified the Darling River as one of those most at risk from extreme ecological changes due to the impact of global warming around the world. The Murray-Darling Basin, Australia’s most important agricultural area, is already prone to droughts and floods – like the 2022 events captured here in the Barwon-Darling river system. As the climate emergency accelerates, seasonal rainfall patterns will continue to fluctuate in potentially volatile ways, with unprecedented consequences for the basin’s residents, businesses and wildlife. Ash from climate-change-driven wildfires in the region can also wash into rivers, making them toxic.

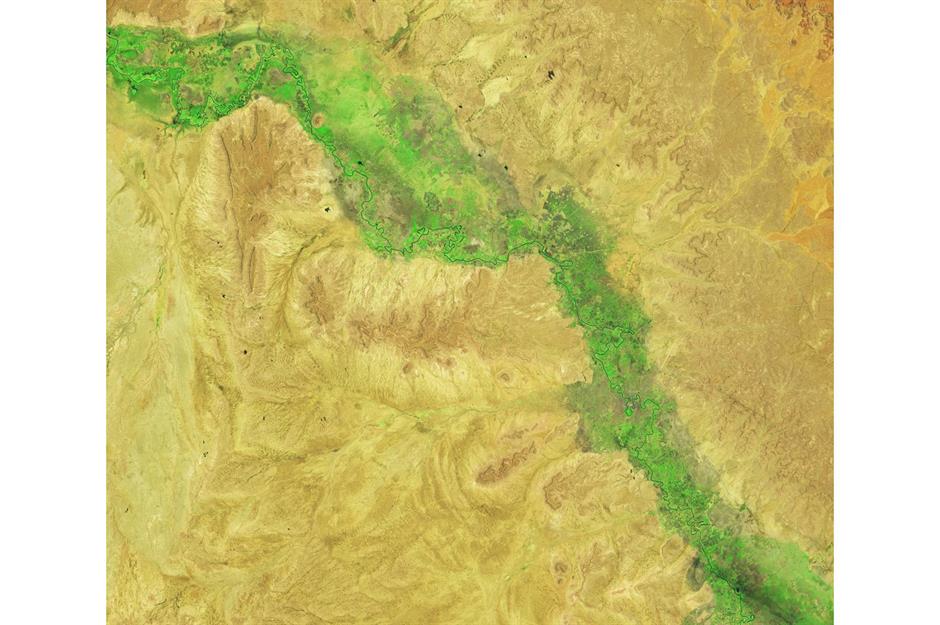

Then: Shebelle River, East Africa

Originating in the highlands of Ethiopia, the Shebelle River (also spelled Shabelle or Shebeli) traverses the eastern Horn of Africa, whose plains were once called the 'breadbasket' of Somalia. While the river is typically subject to seasonal changes in its flow, the past few years have pushed those changes to the extreme. Between 2020 and 2023, the region’s most prolonged drought in recorded history rendered millions of people food insecure and left the Shebelle parched. According to scientists, the drought was only made possible by human-induced climate change. This is the Shebelle River on 12 September 2023.

Now: Shebelle River, East Africa

Within a couple of months of the previous image being captured, the Shebelle River looked unrecognisable after a deluge of heavy rain led to its overflow. As shown here via NASA's satellite imaging from 15 November 2023, extensive flooding submerged previously drought-stricken parts of central Somalia, as well as areas in Ethiopia and Kenya. The floods claimed more than 100 lives from 1 October onwards and displaced more than 700,000 people, with precipitation levels ranging from double to quadruple the average for the three countries.

Then: Mekong River, East and Southeast Asia

The longest river in Southeast Asia and the seventh-longest river on the continent, the Mekong River flows through China, Tibet, Myanmar, Laos (pictured), Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Its historically fast flow earned it the moniker the 'mighty Mekong', while the Mekong delta is known as Vietnam’s 'rice bowl'. Its fields – sustained by nutrient-rich sediment carried downstream by the river’s natural cycles – yield about half of the country’s total rice harvest and around 75% of the Vietnamese population’s calorie intake. But this beautiful, life-preserving waterway is slowly dying.

Now: Mekong River, East and Southeast Asia

Rising global temperatures and hydropower dams are choking its ecosystem; scientists analysing 110 fish species in the lower Mekong noted an 87% decline over the course of 17 years. A healthy, free-flowing lower Mekong is pivotal to the livelihood and survival of the 60 million people that call it home, who not only rely on fish stocks and water-fed rice for sustenance, but income too. Between 2019 and 2021, river levels dropped to their lowest in more than 60 years – here you can see people walking across its dry bed in Vientiane, Laos, in November 2021.

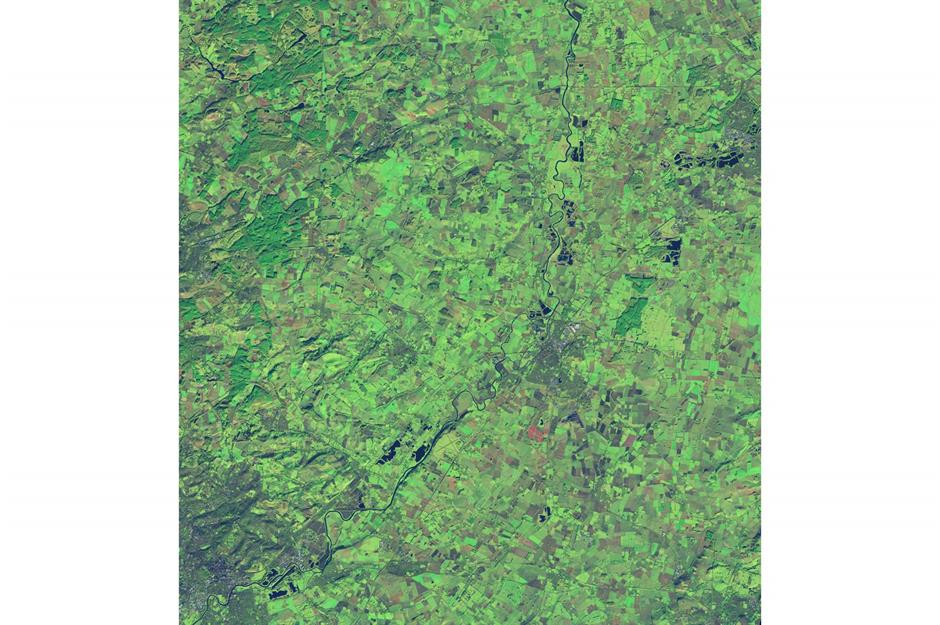

Then: River Trent, England, UK

England’s third-longest river is inextricably linked to the development of the Midlands region. Connecting several counties in the heart of Britain, including Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, the Trent was a major working river throughout the Industrial Revolution until after the Second World War. Long before that, early civilisations settled along the river’s banks, drawn here by the nourishing waters and fertile lands. In this NASA Earth Observatory capture from 5 January 2022, the River Trent can be seen in its typical state.

Now: River Trent, England, UK

But it’s a different story in this image from 4 January 2024. At the turn of the new year, heavy rain from consecutive storms caused the Trent to severely burst its banks, leaving a number of riverside communities saturated. Storm Henk was the most potent of these storms, hitting on 2 January and provoking a major incident to be declared across Nottinghamshire due to widespread flooding along the river. The rise in Britain’s wetter and warmer winters was later attributed to the climate crisis, with meteorologists warning river flooding will only worsen as the planet continues to heat up.

Then: Tigris River, Iraq

The history of the ancient Tigris is entwined with that of civilisation itself. Along its banks is where humans first developed concepts such as agriculture, writing, beer brewing and the wheel – it is also said to have watered the biblical Garden of Eden. Once belonging to Mesopotamia, the Tigris River now predominantly courses through modern-day Iraq, including the cities of Mosul and Baghdad. It empties into the Persian Gulf together with its twin river, the Euphrates. This image of boys boating on the Tigris dates back to 1995.

Now: Tigris River, Iraq

But after decades of war, droughts and desertification, Iraq has been named one of the most climate-change-vulnerable countries by the UN, and its struggles are concentrated in the story of the Tigris. Strangled by dams and dwindling rainfall, the once-powerful river that so many agricultural communities depend upon is drying up. According to the International Organization for Migration, climate factors displaced more than 3,300 families in Iraq’s central and southern regions in the first three months of 2022 alone. In this photo from July 2023, dead fish litter the cracked, dry bed of the Tigris’ fabled marshlands.

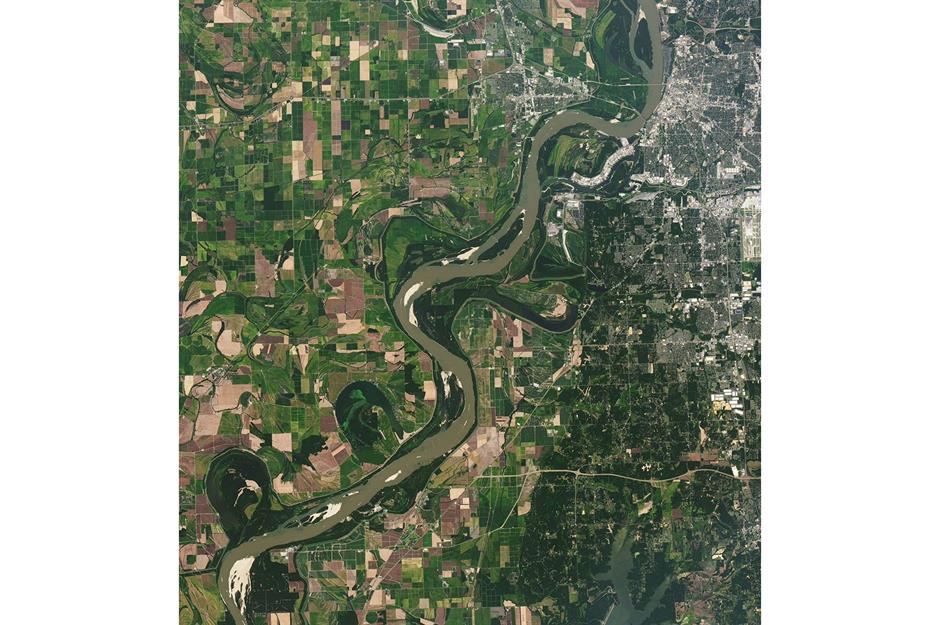

Then: Mississippi River, USA

When measured with its major tributaries, including the Missouri River and the Ohio River, the Mississippi is the longest river in North America. Its drainage basin encompasses a whopping 1.2 million square miles (3.1m sq km) – about an eighth of the entire continent. Rising in Minnesota from Lake Itasca, the Mississippi River flows almost due south before ending at the Gulf of Mexico, around 2,350 miles (3,766km) from where it started. With its tributaries, the great river drains 31 US states and two Canadian provinces to some degree. It’s captured here in September 2021 by NASA.

Now: Mississippi River, USA

Temperatures in summer 2023 were 1.2°C (2.1°F) warmer than average worldwide, with the rampaging heat leaving the Mississippi gasping with thirst. The river’s waning levels hampered barge traffic and threatened drinking water supplies across Louisiana. Tennessee was affected too – this image shows a diminished Mississippi River near Memphis on 16 September 2023, where the waterline was so sunken in places that the riverbed was exposed, echoing the historic lows of 2022. Climate change is also causing harmful algal blooms to form in sections of the river system, as well as damage to its wetlands from stronger hurricanes.

Then: Brahmaputra River, South and Central Asia

Rising in Tibet, the Brahmaputra courses through India and Bangladesh to join with the holy Ganges River. It acts as an important inland waterway between the Indian states of West Bengal and Assam, where raw materials, timber, crude oil and local handicrafts are transported. But life along this river has long been under threat. Taken on 18 September 2019, this picture shows a woman on the river island of Majuli washing pans in the Brahmaputra. As increasingly violent flooding pushes the river past its limits and erodes the island’s shoreline, experts have warned Majuli could disappear by 2040.

Now: Brahmaputra River, South and Central Asia

Together with the Ganges and the Indus, the Brahmaputra River (pictured here in March 2024) forms the veins of the Indian subcontinent to serve around one billion people. But at the hands of climate change and human mismanagement, the unpredictable flow of these life-giving rivers is causing chaos across their basins, with some of the most vulnerable communities being hit hardest. Combined with pollution and industrialisation, our warming planet is compounding flooding and water scarcity by creating harsher monsoons and dry seasons, as well as affecting river-feeding glaciers in the Himalayas.

Then: Danube River, Europe

The Danube, Europe’s second-longest river, passes through 10 countries from the Black Forest to the Black Sea: Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. Its historic banks, still peppered with fortresses and castles today, have witnessed the economic and political evolution of central and southeastern Europe through the ages, and inspired centuries of artists and adventurers. With fairy-tale scenes such as this pelican colony, pictured along the Sulina Channel of the Danube delta in 2003, it’s hard to believe that the great river’s recent reality is closer to a horror story.

Now: Danube River, Europe

In the summer of 2022, a five-month-long historic drought reduced many of Europe’s rivers to shadows of their usual selves, spiking record-breakingly low water levels. The Loire, Rhine, Po and Danube were among those worst affected, with the latter having to be dredged in parts of Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria to deepen its waters and ensure ships could safely navigate passage. Flowing at less than half its typical summer volume, the state of the Danube was largely ascribed to the climate crisis. Here, a farmer walks his cattle across the river’s bare bed in Roseti, southern Romania, on 11 August 2022.

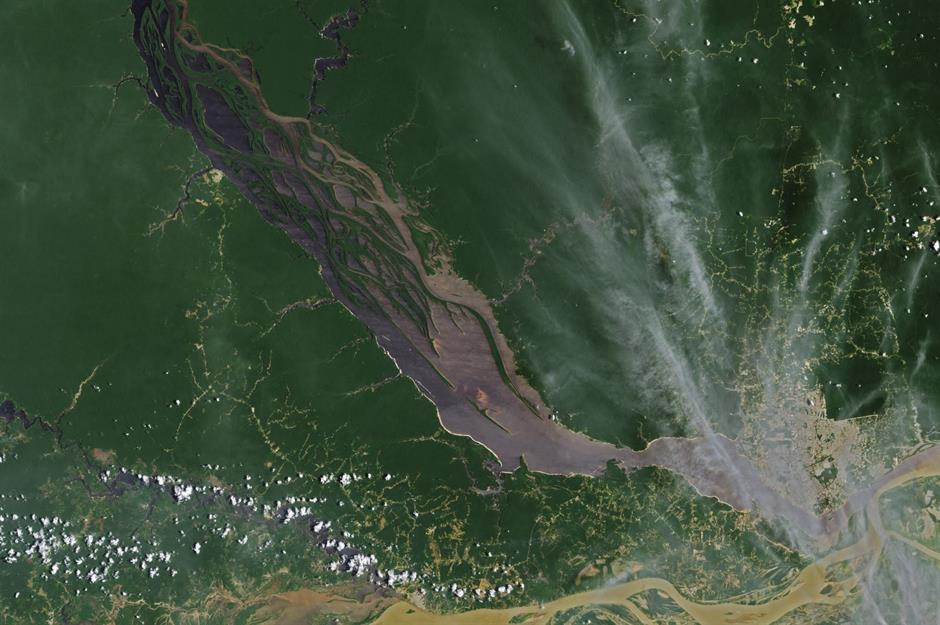

Then: Rio Negro, Brazil

One of the major tributaries of the usually mighty Amazon River, the Rio Negro originates in several headstreams that ultimately enter Brazil from Colombia and Venezuela. Named for its dark waters, it meets with the Amazon at the port city of Manaus, where its jet-black colouring clashes with the yellowish hue of South America’s largest river. Here, NASA Earth Observatory's aerial image shows the Rio Negro on 8 October 2022, where its water sits at 64.3 feet high (19.59m), a typical level for that time of year.

Now: Rio Negro, Brazil

But throughout 2023, the Amazonas region was rocked by a historic drought which scientists have since primarily attributed to climate change. River levels at Manaus on Monday 16 October registered at 44.6 feet (13.59m) – their lowest since records began 121 years ago. This image shows the Rio Negro just a week prior, on 3 October, when its water level was at 50.5 feet (15.14m). The months-long spell of no rain cut off remote villages and stranded boats, with high water temperatures blamed for the deaths of more than 100 endangered river dolphins.

Now check out more images that show why we can no longer ignore the climate crisis

Comments

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature