Spooky real-life locations of American witchcraft

America's bewitching history

The idea of witches as evil servants of Satan was ingrained in 17th-century Christian belief. Puritans took the Bible’s words, 'thou shalt not suffer a witch to live', literally, bringing with them from Europe (with its long history of executing 'witches') to colonial America a catalogue of fears and paranoia. The Salem witch trials were the most famous flashpoint – a culmination of religious extremism, xenophobia, social divides and rivalries between settlers. But the so-called 'Witch City' isn’t the only place in the US with ties to the supernatural.

Click through this gallery to discover the stories behind some of America’s real-life locations of witchcraft, magic and voodoo...

Hartford and Windsor, Connecticut

45 years before anti-witch hysteria infamously swept Salem, Alice ‘Alse’ Young became the first person to be executed in New England for suspected witchcraft. The English-born resident of Windsor, Connecticut was sent to the gallows on 26 May 1647 for reasons lost to history, though it’s possible that she may have been made a scapegoat for a devastating flu epidemic in her town. Young’s sentence was carried out at Meeting House Square in Hartford, where the Old State House (pictured) now stands.

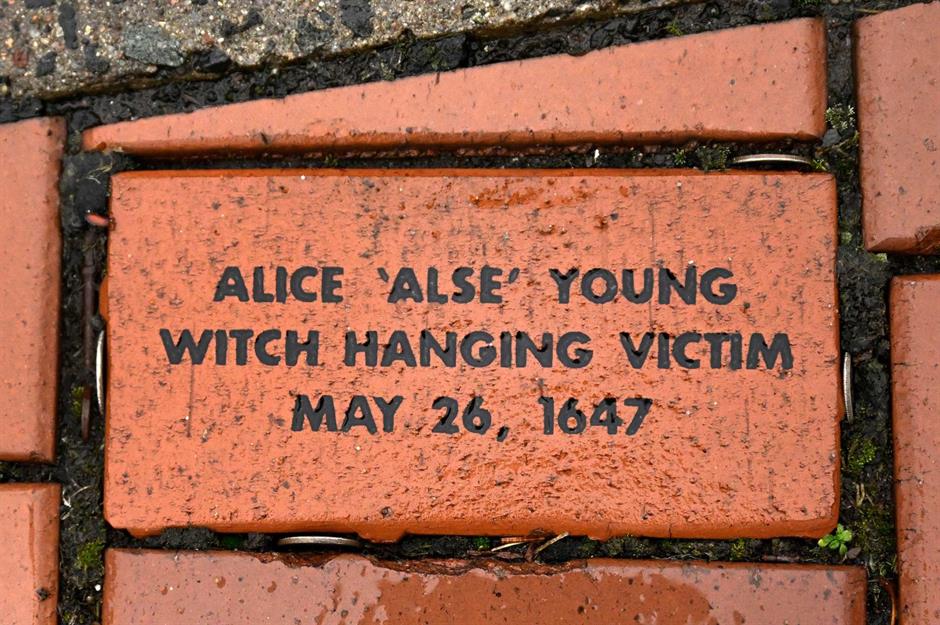

Hartford and Windsor, Connecticut

While Alice Young’s only daughter survived the epidemic, others were not so lucky; her neighbours alone buried four children. This could have led Windsor’s community to accuse Young of witchcraft, one of 12 capital crimes in colonial Connecticut. Within a couple of decades of Alice Young’s death, the so-called ‘Hartford witch panic’ had fully taken hold, resulting in 10 further hangings. In May 2023, the Connecticut State Senate officially pardoned those convicted for witchcraft in the 17th century. This memorial to Alice Young forms part of the Heritage Bricks installation on Windsor’s Central Street.

East Hampton, New York

In February 1658, still long before the notorious Salem trials, what was then the English settlement of Easthampton (now styled East Hampton) purportedly found a witch in their midst. It all started when 16-year-old Elizabeth Gardiner Howell fell gravely ill and was afflicted by feverish visions. The day before she died, she described seeing "a black thing at the bed’s feet" and hopelessly tried to bat it away, repeatedly wailing: "A witch!" Gardiner Howell named her invisible harasser as local woman Elizabeth 'Goody' Garlick, known for her disputes with other villagers who saw quarrelling as the devil's work.

East Hampton, New York

A litany of allegations were subsequently levelled against Garlick, citing her supposed ability to cast evil eyes, summon demon animals and visit physical harm upon both humans and livestock. But thanks to John Winthrop Jr, a vocal witchcraft sceptic and Hartford’s new sheriff (Easthampton belonged to Connecticut colony at the time), she was found not guilty. It’s thought Garlick simply resumed her normal life after being acquitted. While there’s little evidence of an eerie past in celebrity-favourite East Hampton today, attractions like Main Street, Mulford Farm and the Home Sweet Home Museum (where you’ll find this windmill) offer glimpses into its colonial history.

Salem Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts

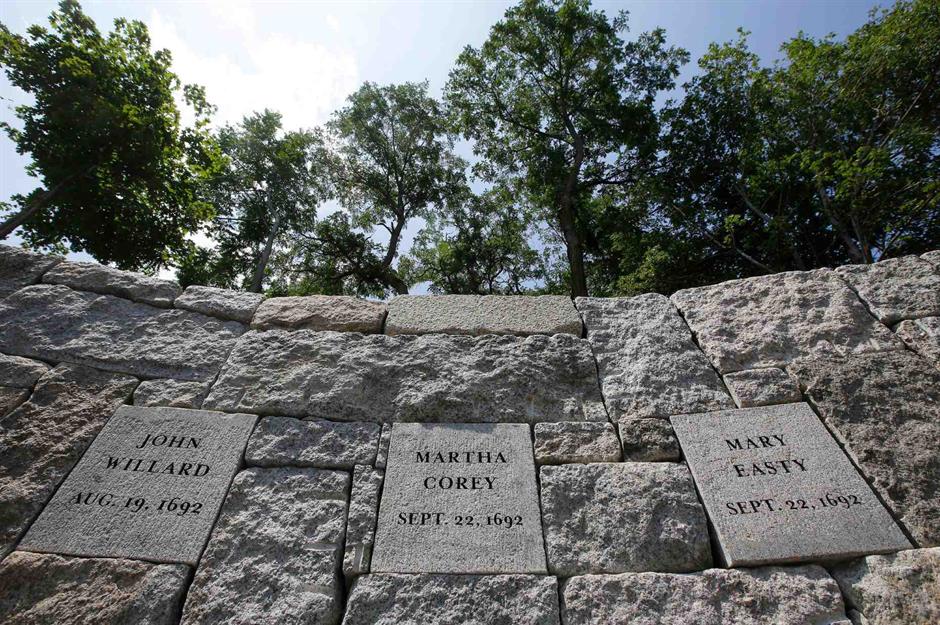

Though it may look simple, the Salem Witch Trials Memorial on Liberty Street in modern Salem (Salem Town in the 1600s) is a powerful monument to the 20 people put to death between 1692 and 1693. A stone slab for every victim, each engraved with their name and the date and means of their execution, juts out from the walled space. It's a place where visitors leave flowers, coins and messages. Dedicated in 1992, the trials’ tricentennial year, the memorial has at its centre a family of locust trees that are believed to be the species used in the hangings.

Salem Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts

At the entrance to the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, fragments of the victims’ innocent pleas are chillingly etched into the ground. Suspicions first swept Salem in early 1692, when a group of young girls started displaying odd symptoms such as violent contortions and sudden screaming outbursts. Explained away by a local doctor as supernatural possession, the witch hunt began. By the time the trials came to an end in May 1693, more than 200 people in Salem Village (now Danvers), Salem Town, Andover, Ipswich and Topsfield had been accused. It was only in July 2022 that Salem’s last convicted 'witch', Elizabeth Johnson Jr, was exonerated.

The Witch House, Salem, Massachusetts

The girls afflicted with the symptoms were pressed by Massachusetts Bay’s colonial magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne to give the names of the women who had bewitched them. Their fingers pointed at Tituba, an enslaved woman indentured to the Parris family, homeless woman Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, who was poor and elderly. The three women were brought to Corwin and Hathorne for questioning. Good and Osborne denied the charges, whereas Tituba confessed and – likely in the hope of saving herself – warned the puritanical parish she wasn’t the only witch among them.

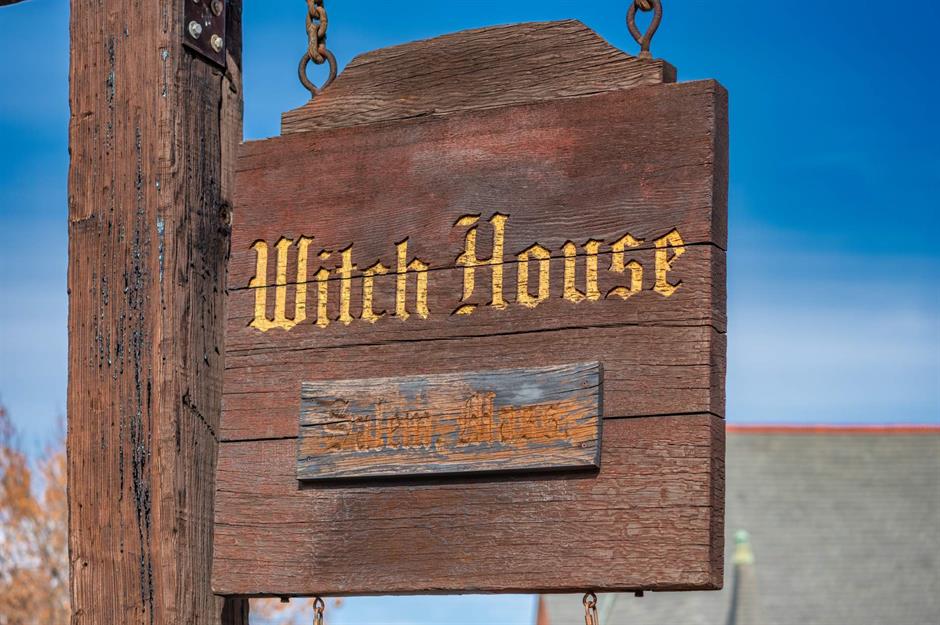

The Witch House, Salem, Massachusetts

Jonathan Corwin was living in this house at the time of the witch trials, having bought it in 1675. Better known as the Witch House, it is the only structure still standing in Salem with direct ties to the trials and it is open to the public today. Corwin was one of several judges to convict men and women of witchcraft in 1692, conducting much of the questioning at the Salem Village Meetinghouse. The original meetinghouse is no longer there, but a plaque commemorating the site lies adjacent to the Danvers Witchcraft Victims’ Memorial. Some say Corwin also carried out interrogations in his home, but this is unproven.

Rebecca Nurse Homestead, Danvers, Massachusetts

After Tituba’s confession in March 1692, paranoia spread like wildfire. Over the next few months, accusations of witchcraft were lodged against even loyal church-goers like Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse, as well as Sarah Good’s four-year-old daughter. At this point, the examinations of alleged witches stepped up a gear: the colony’s governor ordered the establishment of a dedicated Court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) for witchcraft cases. This led to Salem Village convicting and killing its first ‘witch’ – Bridget Bishop – in June 1692.

Rebecca Nurse Homestead, Danvers, Massachusetts

Rebecca Nurse, labelled 'a perfect example of good Puritan behaviour' by the 17th-century media, was executed for witchcraft a month later, alongside four other victims. Pious yet hot-tempered, she had raised eight children in this farmhouse and was 71 when she was led to the noose. Like many of the accused witches, Nurse was known to have previously crossed swords with the Putnams, a powerful local family whose daughter was among those experiencing the 'fits'. Though a jury initially found her not guilty, a review of the verdict saw Rebecca Nurse condemned to death. Her homestead has since been preserved as a museum.

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Salem, Massachusetts

Located next to the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, the Old Burying Point (also known as Charter Street Cemetery) is the oldest burial ground for European settlers in Salem and one of the oldest in the US. It dates back to around 1637 and holds the remains of several prominent figures from the witch trials era, though not the accused themselves, who were typically buried in secret by their grieving loved ones. Judge John Hathorne, colleague of Jonathan Corwin during the witchcraft examinations of 1692, was buried here in 1717 – having never apologised for his role.

Old Burying Point Cemetery, Salem, Massachusetts

Simon Bradstreet, the last governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony under its original charter, is also interred here. He was an outspoken critic of the witchcraft trials and his funeral was attended by Samuel Sewall, the only judge known to have expressed regret. Towards the far right of the cemetery is the grave of Nathaniel Mather, son and brother respectively of the Reverends Increase and Cotton Mather. Both ministers denounced the use of 'spectral evidence' (reported dreams and visions) as a means with which to convict witches. In October 1692, spectral evidence was disallowed at the trials, and the conviction rate started to fall.

Proctor’s Ledge Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts

The Salem witch trials continued with waning intensity until early 1693; by May, anyone still imprisoned on witchcraft charges was pardoned and released. But it was already too late for the 20 people falsely convicted during the trials. 19 were hanged, while Giles Corey (husband of fellow victim Martha Corey) was tortured to death. Seven accused witches are also known to have died in jail. For a long time, a place called Gallows Hill was thought to be the mass execution site from the trials. Only in 2016 did historians (Emerson Baker, pictured, among them) verify that the hangings took place on Proctor’s Ledge, below the hill.

Proctor’s Ledge Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts

One of the victims was John Proctor, killed in August 1692 for publicly speaking out against the trials. The parcel of land now called Proctor’s Ledge was named after his grandson, who bought the site knowing its tragic history. On 19 July 2017, a memorial to those executed there – partially funded by descendants of the 'witches' – was finally dedicated. The date corresponded with the same day in 1692 that Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin and Sarah Wildes lost their lives.

Salem Witch Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Four years after the largest and most lethal witch hunt in American history, the Massachusetts General Court – which later ruled the Salem trials unlawful – declared a day of fasting to honour the deaths of those wrongly condemned. In 1711, colonial authorities formally exonerated some of the accused and compensated their families. Several possible explanations have since been floated for the strange behaviour of those originally accused. These range from juvenile delinquency and imitating voodoo practices shared with them by Tituba, to illnesses like convulsive ergotism, which stems from eating rye infected with a hallucinogenic fungus.

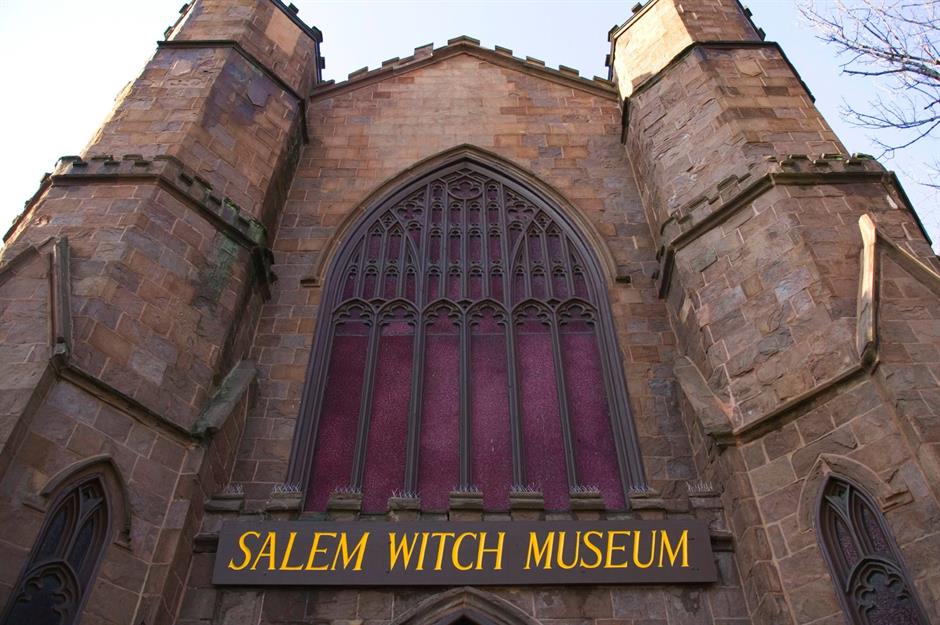

Salem Witch Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Centuries after the events of 1692-93, Salem has become known as ‘Witch City’, and is a popular Halloween destination and place of pilgrimage for modern pagans. The Salem Witch Museum, on Washington Square North, focuses not only on the trials themselves, but also the legacy of 'witch hunts' around the world. Its digital 'Witch Hunt Wall' project and in-house 'Witches: Evolving Perceptions' exhibit show how human nature often compels us to look for someone to blame in times of hardship and uncertainty.

House of the Seven Gables, Salem, Massachusetts

The legacy of the Salem witch trials is also symbolised by the House of the Seven Gables, which lends its name to the 1851 novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne. The author, though his name is styled different, was the great-great-grandson of Judge John Hathorne, whom you’ll remember from earlier in this gallery. Hawthorne’s book The House of the Seven Gables is set in mid-19th-century Salem and was inspired by the legend of a curse supposedly placed on his own family by one of the witches sentenced to death by his unrepentant ancestor.

House of the Seven Gables, Salem, Massachusetts

Visitors can enter the real House of the Seven Gables (also known as the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion) today, which dates back to 1668. New England’s witch trials were also referenced in another Nathaniel Hawthorne novel, The Scarlet Letter, as the character of Mistress Hibbins is named for Ann Hibbins, who was executed for witchcraft in Boston in 1656. Salem’s history has infiltrated almost every corner of popular culture, and the trials were notably dramatised in Arthur Miller’s play, The Crucible, where they became an allegory for the anti-communist witch hunts of 1950s America.

Historic Voodoo Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana

While witchcraft was typically seen as the antithesis of religion, voodoo is a long-standing religion in its own right. It’s possible that Tituba, who may have been a South or Central American woman previously enslaved in Barbados, would have been exposed to voodoo before arriving in New England. There, she cared for the children of Salem’s minister Samuel Parris, and his daughter Betty was one of the first to exhibit the odd convulsions. Tituba later recanted her confession of witchcraft, saying that Parris had beaten it out of her. After 13 months in jail, an anonymous do-gooder finally paid her bail and she disappeared from the history books.

Historic Voodoo Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana

Today, the spiritual home of voodoo in America is New Orleans. At the Historic Voodoo Museum in the city’s French Quarter, visitors can learn more about this often-misunderstood religion, which has its roots in West Africa and travelled to the Americas with the slave trade. You can take a tour of the museum interior and its fascinating collection of cultural artefacts, as well as join a museum-hosted walking tour of New Orleans, encompassing other notable sites and attractions associated with voodoo around the city.

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana

One of the Big Easy’s most famous voodoo practitioners was Marie Laveau, a Black Creole woman lauded as 'the witch queen'. Born around the turn of the 19th century, she was worshipped in her community for reportedly having the power to heal the sick and provide protection against negative energy. Her services aided people on both sides of the city’s racial and socio-economic divides, who would seek advice on everything from marital affairs and domestic disputes to financial and medical issues.

St Louis Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana

There are several locations in and around New Orleans where Marie Laveau’s voodoo legacy has survived. These include Congo Square and the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, favoured sites of hers for worship and ritual. Following her death in 1881, the witch queen is believed to have been buried in St Louis Cemetery No. 1, which is often included as a stop on ghost tours of the city. Though disputed by some, Plot 347 is said to be Laveau’s final resting place. Candles, money, flowers and personal gifts are typically left here by those paying their respects.

Historic Bell Witch Cave, Adams, Tennessee

While the so-called witches of America’s original 13 colonies were innocent victims, the same can’t be said for the legendary Bell Witch of Tennessee, who terrorised one family in the 1800s.The Bells lived on a farm in Robertson County without incident for 13 years, until their peace was shattered by a malevolent entity. In the summer of 1817, the family noticed strange animals appearing on their land and haunting sounds echoing around their cabin. Soon, the noises evolved into a disembodied voice speaking directly to them, and a physical force so violent it knocked young Betsy Bell unconscious.

Historic Bell Witch Cave, Adams, Tennessee

The Bell Witch never showed her face but is thought to have been the spirit of Kate Batts. A disgruntled neighbour seeking revenge against the patriarch John Bell, she claimed he cheated her out of a land purchase and vowed to kill him. When he did pass away in 1820, she was credited with his demise – making Tennessee the only state to ever officially attribute a death to the supernatural. Today, visitors can carry out their own paranormal investigations of the Bell Witch’s supposed cave lair, explore a replica of the Bell family cabin (pictured) or take a tour by lantern light.

Seneca Creek State Park, Montgomery, Maryland

As cult horror movies go, The Blair Witch Project has got to be one of the most iconic ever made. Produced for just £46,000 ($60,000), around £87,000 ($113,000) in today's money, the 1999 flick follows three student filmmakers who go missing in the woods while shooting a documentary on local folklore. Though a work of fiction, the 'found footage' cinematic technique (where actors film themselves on handheld cameras) was intended to make it feel real.

Discover scary horror film and TV locations you can actually visit

Seneca Creek State Park, Montgomery, Maryland

In the movie, the characters Heather, Michael and Joshua interview residents of the Maryland town of Burkittsville about the myth of the Blair Witch. They then attempt to track down the witch's woodland home in 'Black Hills Forest', before ultimately becoming her next victims. The forest setting was mostly provided by Seneca Creek State Park, around 25 miles (40km) from Burkittsville, which is far more beautiful and less foreboding in reality. Though the legend of the Blair Witch was invented by the film’s directors, it was said to be partially inspired by the tale of the Bell Witch of Tennessee.

Rehoboth Beach, Delaware

Each October around Halloween, the people of downtown Rehoboth and Dewey Beach take to the streets for the annual Sea Witch Festival. What started more than 30 years ago as a humble one-day event has now grown into a bumper three-day celebration of free festivities, including parades, costumed fun runs, scavenger hunts, live music and classic horror movie screenings. The guest of honour is always Hilda the Sea Witch, whose giant green inflatable head takes centre stage in the procession along Rehoboth Avenue. The 2024 dates for the festival are 25-27 October.

Rehoboth Beach, Delaware

The legend of the Sea Witch is tied to the sinking of the HMS DeBraak, a British Royal Navy brig which foundered just off Cape Henlopen in 1798. Allegedly laden with riches, the wreck has never been found. Though many have tried, all attempts to salvage the rumoured treasure ship have returned empty-handed – thanks in no small part to the capricious weather that rules these waves. This has led Delaware’s coastal community to suggest that the water, and the wreck, is protected by a higher power. The Rehoboth Beach Sea Witch Festival is one way of trying to appease her.

Spadena House, Los Angeles, California

Also known as the Witch's House, this whimsical cottage isn't your typical Beverly Hills mansion. It was originally built in 1921 for a silent movie studio based in Culver City, where it was used as offices and dressing rooms before being moved to its present zip code in 1934. The 1920s and 1930s saw a trend for storybook-style architecture sweep America, and Spadena House – with its pointy, drooping roof and distressed paintwork – is a prime example of it.

Spadena House, Beverly Hills, California

While it may look as though the witch from Hansel and Gretel could come staggering out at any moment (there are signs from 'The Witch' dotted around the grounds), Spadena House actually belongs to LA real estate agent Michael J Libow. After showing it to a client in the 1990s who wanted to demolish it, Libow bought the fairy-tale abode to preserve it as a monument to America’s fascination with magic and make-believe. While the property is not open to the public for tours, you can still catch a good view from the sidewalk.

Comments

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature