The earliest photos of France will astonish you

Early images of France

The 19th century was a tumultuous one for France. It began under the rule of Emperor Napoleon I, saw the restoration of the monarchy and ended with the establishment of the Third Republic. Amidst this turmoil, French innovation gave the world photography. The world's earliest photograph was taken in France and, as the century progressed, a series of pioneering photographers helped document the rapidly changing world around them.

Click through the gallery to explore stunning images of 19th-century France…

1826: The world's first photograph

Although the public was first introduced to photography in the late 1830s, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had already succeeded in capturing the first ever photograph over a decade earlier. The hazy image, taken from the window of his workroom, shows outbuildings, trees and the surrounding landscape.

Creating it was a laborious process that involved placing a polished pewter plate coated with bitumen of Judea inside a camera obscura and leaving it exposed for several hours. The plate was then rinsed with a mixture of oil of lavender and white petroleum, which dissolved the bitumen, not hardened by light, to reveal a direct positive image.

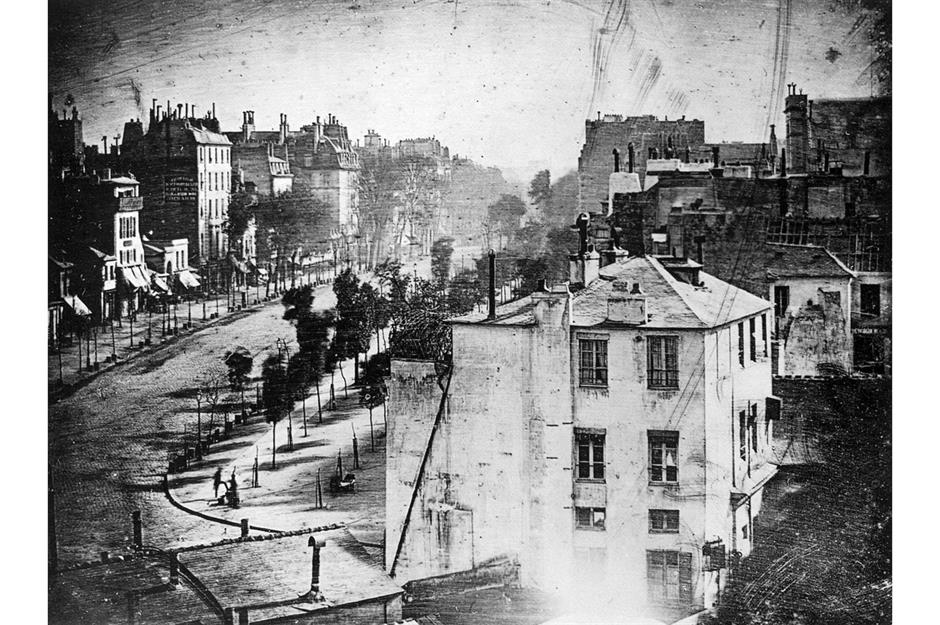

1838: A person is caught on camera for the first time

A shoe-shiner and his client quietly going about their business on the Boulevard de Temple in Paris were the very first people caught on camera. Louis Daguerre captured the image using a method that would be named after him – the daguerreotype.

Daguerre’s process involved creating a detailed, one-of-a-kind image on a copper plate coated with silver, without the use of a negative. The exposure time ranged from three to 15 minutes, meaning that any moving objects would not be visible in the final image. Only stationary subjects, like the shoe-shiner and his client, remained in place long enough to be recorded, unknowingly securing their place in photographic history.

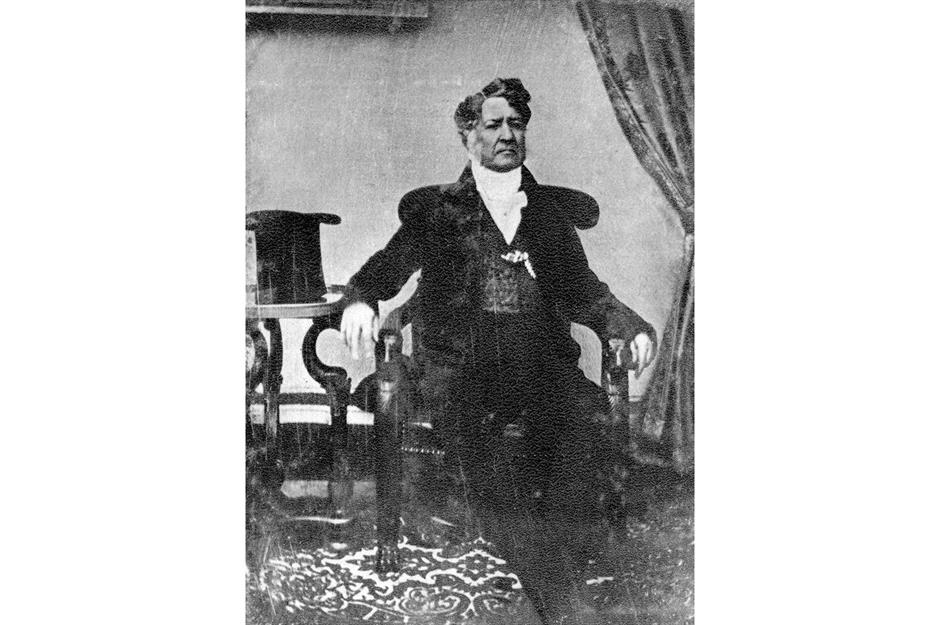

1840s: Louis Philippe I, King of the French

Initially promising a liberal regime, Louis-Philippe's reign soon faced worker uprisings, assassination attempts and growing unrest. Over time he became increasingly authoritarian, alienating both republicans and monarchists. In 1848, amid revolution, he was forced to abdicate and fled to England, marking the end of monarchy in France.

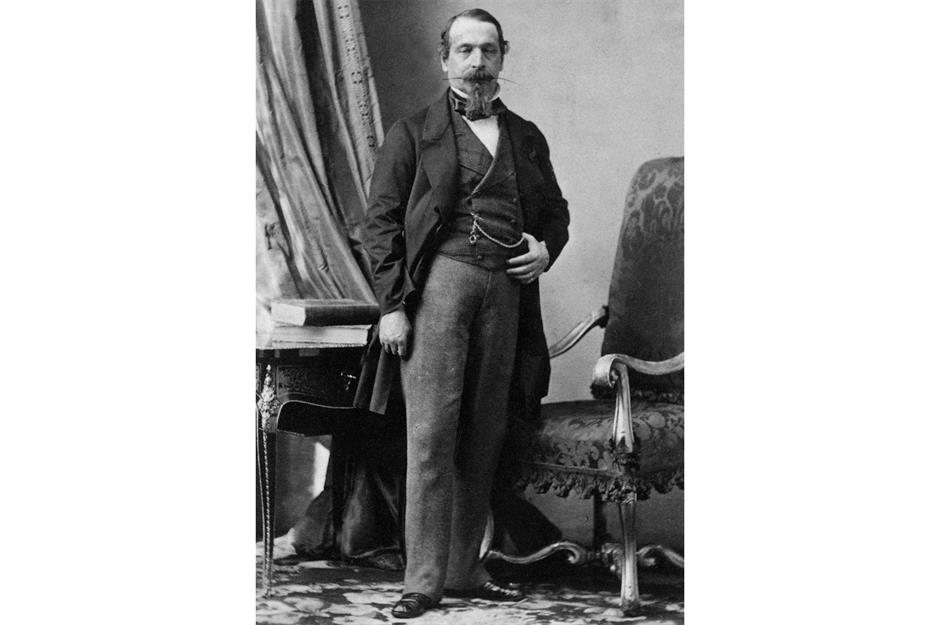

1850s: Napoleon III

Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was the nephew of France’s legendary first emperor, Napoleon I, and shared his uncle’s imperialist tendencies. He made several attempts to seize power before the ousting of Louis Philippe finally gave him a legitimate opportunity. By evoking the Napoleonic legacy and positioning himself as a unifying figure, he was elected President of the French Second Republic in 1848.

When constitutional limits prevented him from seeking a second term, he orchestrated a coup d’état in 1851. A year later, after a referendum, he declared himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, marking the beginning of the Second French Empire.

Love this? Visit our Facebook page for more historic images and travel inspiration

1854: Village de Murols

This incredible shot of squat thatched houses was taken in the village of Murols in what is now the Midi-Pyrenees region of Southern France. The humble dwellings offer a fascinating insight into the spartan reality of French rural life in the mid-19th century.

The photographer was Édouard Baldus, who abandoned his unsuccessful painting career to take up the new medium of photography in the early 1850s. He went on to gain international acclaim and commissions from government and industry. His photographs are now considered early masterpieces of the art.

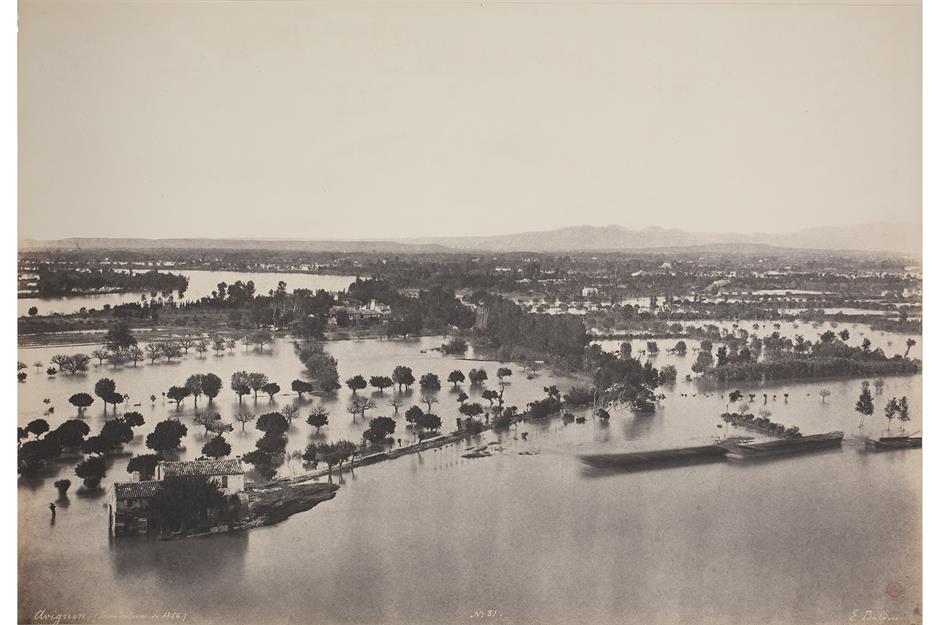

1856: Floods, Avignon

In May and June of 1856, a period of unrelenting rain caused several of France’s major rivers to flood, resulting in extensive damage across the country. Houses, churches and bridges were destroyed, livestock swept away and railway lines uprooted. One of the worst affected areas was the Rhȏne Valley, where entire sections of Lyon and Avignon were destroyed.

Commissioned by the government to record the event, Baldus travelled to the region where he took a series of dramatic images of the devastation. This image is part of a six-part panorama, captured from the cathedral terrace in Avignon, which measured over seven feet (2.1m) in length.

1856: Le Havre

One of France’s largest port towns, the history of Le Havre is intricately woven with that of its harbour. A hugely important trading centre in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was also the main point of departure for emigrants heading to the new world. It’s pictured here in its heyday in an image by Gustave le Gray, the central figure of French photography in the 1850s.

The town would later serve as the setting for Jean-Paul Sartre’s classic existentialist novel Nausea (1938), but would be almost completely destroyed during World War II. Rebuilt in a modernist style by the architect Auguste Perret, Le Havre today bears little resemblance to the picturesque port seen here.

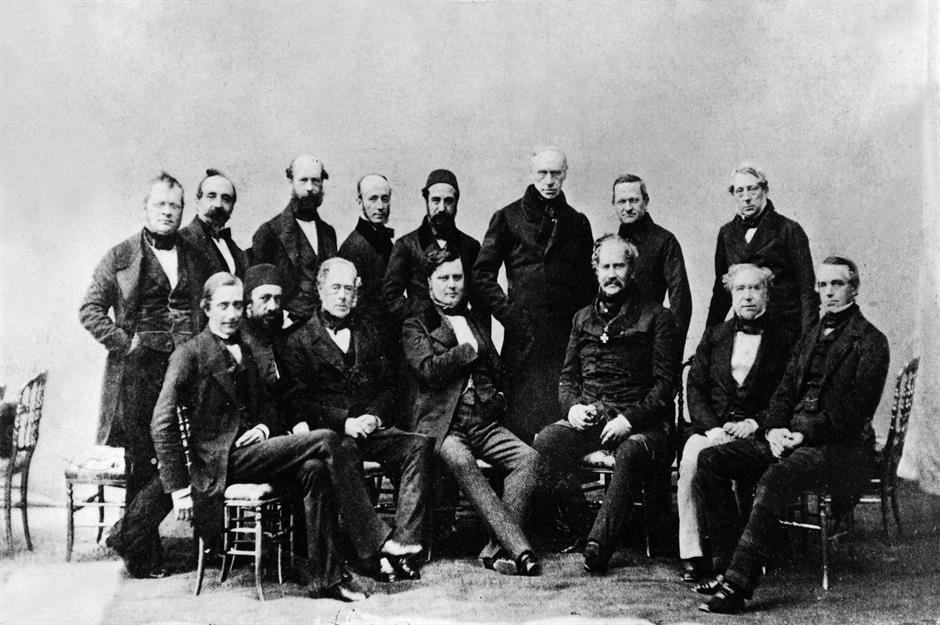

1856: Treaty of Paris

During the Crimean War (1853-1856), France allied itself with Britain and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, giving Napoleon III the chance to realise one of his most cherished goals – an alliance with Britain that would check Russian expansion in the Mediterranean.

After two years of bloody conflict which had claimed the lives of some 500,000 soldiers, representatives of the countries involved came together at the Congress of Paris in February 1856 to negotiate a peace treaty. On 30 March, the Treaty of Paris was signed. Here, the ministers of the nations involved gather for a formal group portrait during the negotiations.

c.1861: Marseilles

When Baldus captured this image of the Old Port of Marseille in 1861, the city was expanding into a major Mediterranean trading hub. Trade with France’s colonial territories was growing, and Marseille was becoming a key gateway for the French Empire’s overseas commerce.

The decline of Barbary piracy between 1815 and 1830 and France’s invasion of Algeria in 1830 made shipping routes safer, helping the port thrive. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 would further boost its fortunes, cementing Marseille’s role as a crucial link between Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

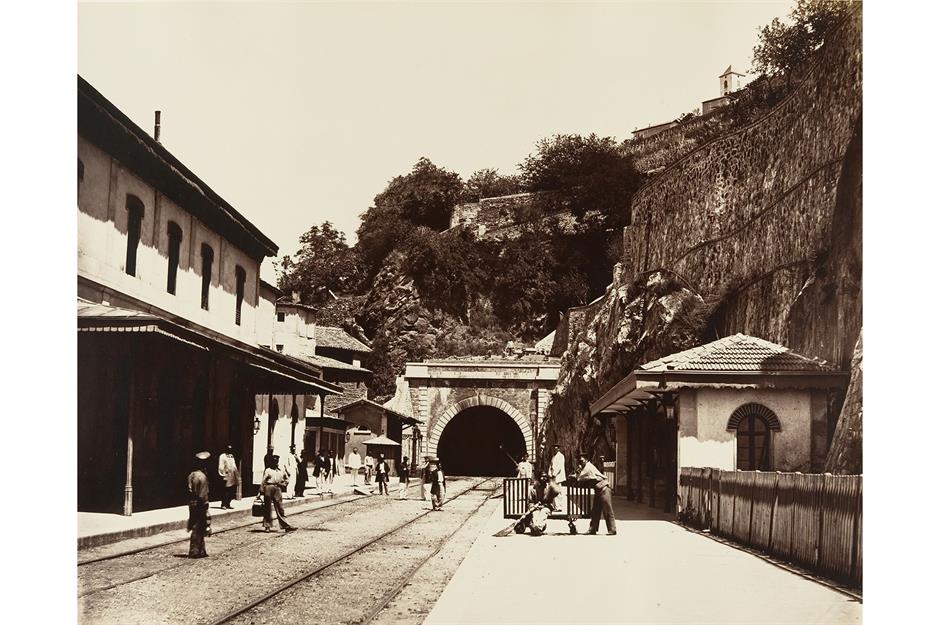

1861: Station and rail tunnel, Vienne

This view of Vienne train station and the tunnel approaching it comes from a series that Baldus produced for the Paris-Lyon-Mediterranée Railway Company. It shows the route from the city of Lyon in the south of France to Toulon, a historic naval city on the Mediterranean coast.

France’s railway network expanded rapidly after the opening of its first passenger line in 1837, which ran between Paris and Le Pecq. By the 1850s, six major railway companies dominated the network: Compagnie de l'Est (East), Compagnie du Nord (North), Compagnie de l'Ouest (West), Compagnie du Paris-Orléans (PO) (which extended beyond Orléans to Bordeaux), Compagnie du Midi (covering the deep south) and the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM) railway, linking Paris to the Mediterranean coast.

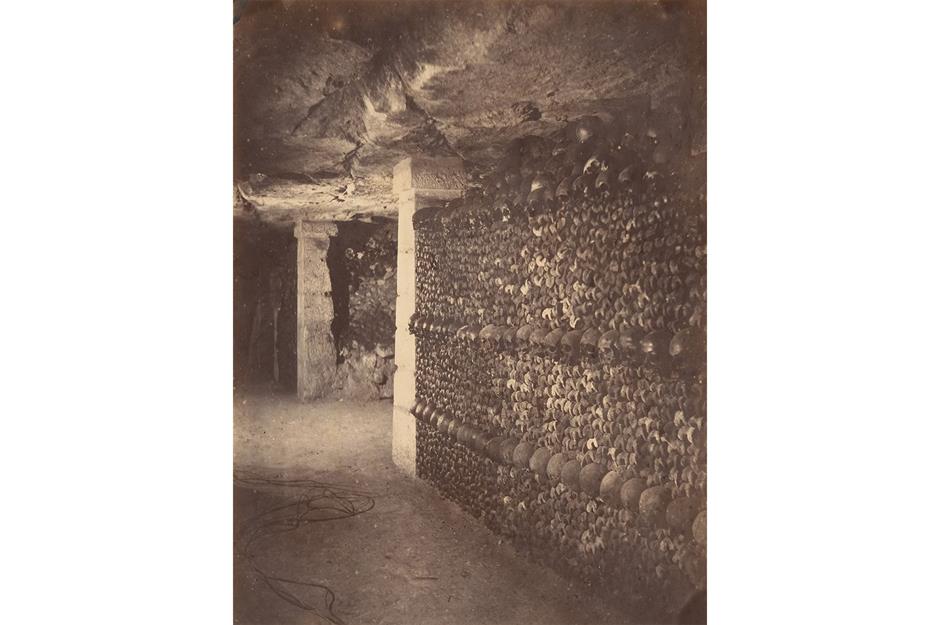

1862: Catacombs, Paris

The Paris Catacombs originated in the late 18th century, when public health concerns over overcrowded cemeteries led authorities to transfer millions of skeletal remains into abandoned limestone quarries beneath the city. The first major transfers began in 1786, and by 1809, the site was opened to visitors by appointment, offering eerie torchlit tours.

However, they remained largely unknown to the wider public until Félix Nadar, a pioneering photographer, successfully captured the first underground images of the Catacombs in the 1860s. Using a new form of artificial lighting, he illuminated the pitch-dark tunnels, producing images that helped cement the Catacombs as a major tourist attraction.

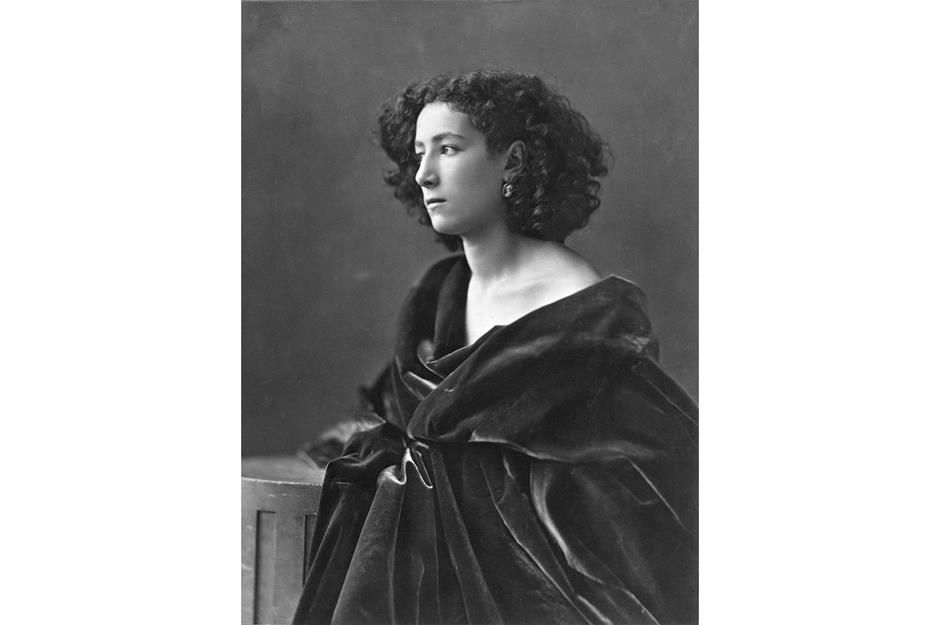

c. 1864: Sarah Bernhardt

Taken by Nadar in his role as celebrity photographer, this image shows a young Sarah Bernhardt, then only around 20 years old and virtually unknown. She would go on to become the greatest French actress of the 19th century and achieve an unprecedented level of worldwide fame.

Bernhardt played the greatest roles written by Dumas, Molière and Shakespeare, was one of the first women known to have played the title role in Hamlet and appeared as Queen Elizabeth in one of the earliest feature films. She is also widely thought to have inspired the character of La Berma in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

1870: Palace of Versailles used as a Prussian hospital during the Franco Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) had enormous consequences for Europe, leading to the fall of the Second French Empire and the rise of Germany as the dominant continental power following its unification under Prussian leadership.

Prussian troops reached Paris on 19 September 1870, beginning a four-month siege that ended with the city's surrender on 28 January 1871. During the occupation, the Palace of Versailles was repurposed, and its opulent Gallery of Mirrors was converted into a military hospital for wounded Prussian soldiers.

1870: Prussian army at Château Fort de Sedan on the day France surrendered

The Battle of Sedan on 1 September 1870 proved to be the decisive conflict of the Franco-Prussian War. Within a single day, 17,000 French troops were killed or wounded, mown down by the formidable Prussian artillery. Napoleon III had no choice but to surrender and was taken prisoner with 103,000 of his soldiers.

It was a humiliating defeat, bringing a sudden end to the Bonaparte dynasty. When the news reached Paris, a popular uprising overthrew the imperial government and the Third Republic was established in its place.

Now check out incredible vintage photos of the world's most famous landmarks

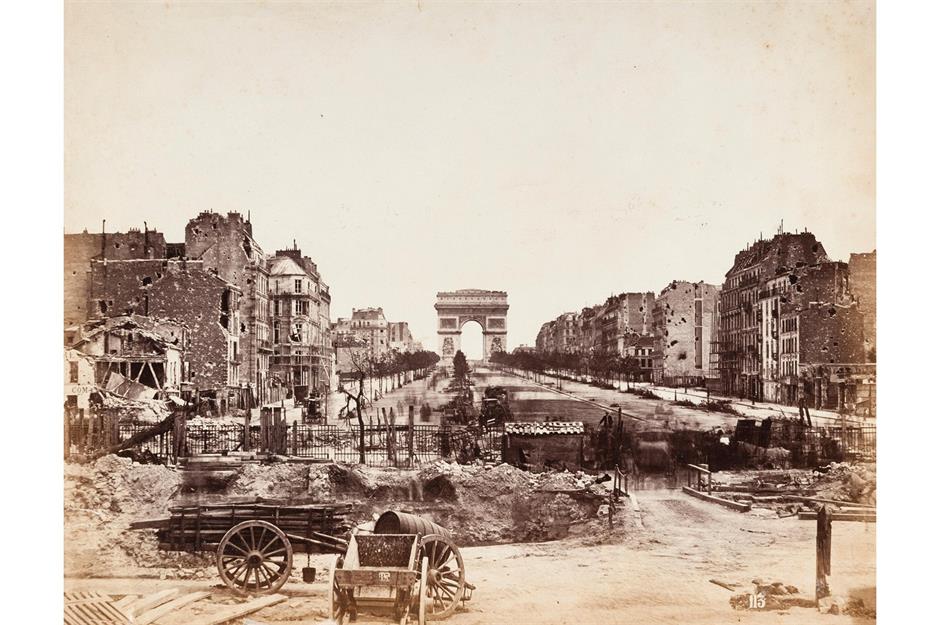

1871: Champs-Élysées, Paris in ruins after the Siege of Paris

Despite Napoleon III’s surrender, the new government refused to accept Prussian terms, prolonging the war for another four months. Paris was subjected to a prolonged siege, culminating in a heavy artillery bombardment – with 300 to 400 shells fired into the city daily in January 1871.

Casualties were relatively low, but the psychological impact and starvation were devastating. Most destruction occurred in working-class neighbourhoods in the east of the capital. The most notable damage to central Paris occurred later, during the Paris Commune uprising in May 1871.

1871: Ruins of Tuileries Palace, Paris

Following France’s defeat, tensions boiled over in Paris, where thousands of working-class Parisians rebelled against the Royalist-leaning government, which had retreated to Versailles. On 18 March 1871, they declared Paris an independent Commune, seeking a radical socialist and democratic government in opposition to the national regime.

The Paris Commune lasted 72 turbulent days, during which barricades were erected, hostages were executed and major government buildings were burned – including the Hôtel de Ville and the Tuileries Palace. Although the Hôtel de Ville was later rebuilt, the Tuileries Palace remained in ruins until its demolition in 1883.

1871: Hortense David, Communard

The commune was eventually savagely put down. During the 'semaine sanglante' (bloody week), around 20,000 Communards, as well as 750 government troops were killed. Over 38,000 would eventually be arrested with more than 7,000 deported.

Women played a significant role in the insurrection, both as fighters and activists. Some were accused of being 'pétroleuses' (female arsonists), allegedly setting fire to buildings during the final days of the Commune. However, historical evidence for widespread female-led arson is disputed, as many of these accusations were likely exaggerated to justify harsh repression. A Parisian portrait photographer captured this image of a female Communard after gaining access to a makeshift prison in Versailles.

1878: Exposition Universelle, Paris

The end of the Franco-Prussian War ushered in a new age of optimism and prosperity across much of Europe, which would be fondly remembered as the Belle Époque (or 'Beautiful Era'). France was especially eager to celebrate its recovery, and what better way to do this than with the largest World's Fair ever held?

The enormous Exposition Universelle of 1878 covered 185 acres, with grand displays of fine art, architecture and the latest technological innovations from across the globe. Highlights included Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, Edison’s phonograph and the completed head of the Statue of Liberty.

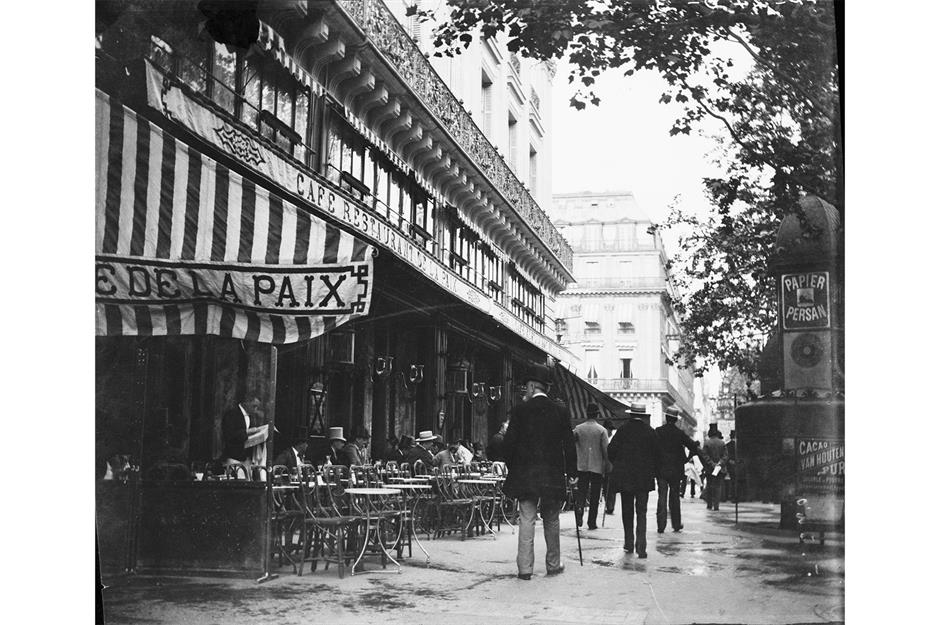

1886: Café de la Paix, Paris

Few Parisian locales better epitomise the spirit of optimism, prosperity and cultural renewal which defined the Belle Époque than the Café de la Paix. Located on the Place de l’Opéra, in the heart of Baron Haussmann’s Grands Boulevards, this venerable institution opened its doors in 1862, its opulent Napoleon III décor welcoming some of the era’s most legendary names.

Famous customers of the era included Victor Hugo, Guy de Maupassant, Émile Zola, Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle.

1888: Eiffel Tower Under Construction, Paris

It would be strange indeed to think of Paris without the Eiffel Tower, the city’s most iconic landmark. But there’s something even stranger about seeing it in a state of semi-completion, as in this image taken in 1888 during the early stages of its construction.

Built as the centrepiece of the 1889 World's Fair, which coincided with the centennial anniversary of the French Revolution, the tower would become the tallest structure in Paris and, for many years, the world. A marvel of precision engineering, it was constructed using 7,300 tonnes of iron, 18,000 individual metallic parts and 2.5 million rivets.

1890s: Café, Normandy

Normandy’s wealth of lovely seaside towns turned it into a popular tourist destination during the 19th century, while the Impressionists were drawn to its unique light, beauty and charm. However, daily life for the vast majority of those living in the region remained very simple – as this image of a couple drying washing outside their café reveals.

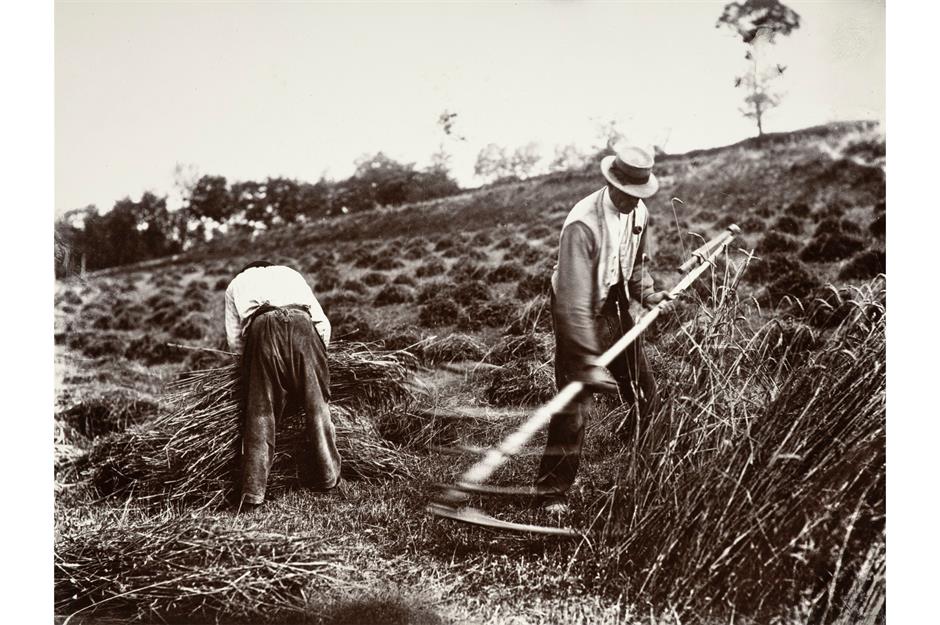

1890s: Faucheurs, Somme

These 'faucheurs' (reapers), pictured in the Somme using scythes to laboriously gather crops by hand, highlight the daily grind of peasant life. The photographer was Eugène Atget, best known for his street scenes of Paris. His unique compositional approach has led to him being admired as a forerunner of Surrealism and the modern art of photography.

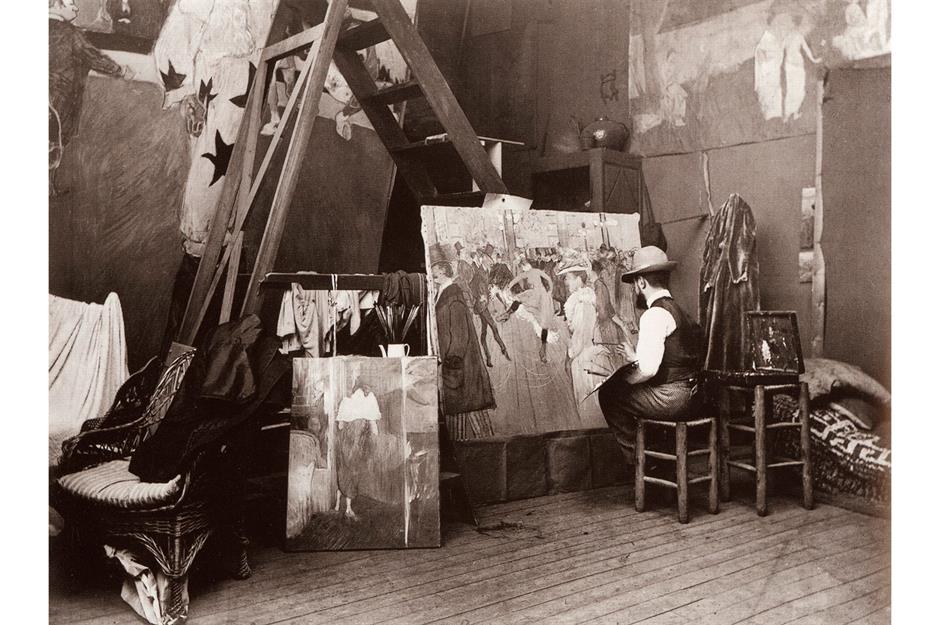

1890: Toulouse-Lautrec painting La Danse au Moulin Rouge

The paintings, prints and posters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are among the most iconic and evocative records of Belle Époque Paris, perfectly capturing the bohemian lifestyle of the cafés, cabarets and brothels frequented by its artistic community.

Here he is captured in his Montmartre studio working on La Danse au Moulin Rouge (1890), one of the earliest images he painted of the famous Parisian cabaret, which had only opened its doors a few months earlier. He would go on to depict its colourful dancers and customers many times over, but this particular painting was purchased by the owners and hung above the bar.

1895: Train crash at Montparnasse Station, Paris

One of the most famous rail disasters in history occurred on 22 October 1895, when the Granville-Paris Express ploughed through the front wall of the Gare Montparnasse, crashing into the street below. The train had been running late and, trying to make up for lost time, the driver approached the station too fast.

Unfortunately, the train’s air brakes were defective and it overran the buffer stop at a speed of 25 miles per hour (40km/h). Miraculously, all the passengers survived, although a newspaper vendor on the street was killed by falling masonry. The dramatic images of the aftermath are among the most iconic in transportation history.

1895: Shoppers outside Le Bon Marché, Paris

Le Bon Marché was the first department store in Paris and its innovative commercial practices including fixed prices, home delivery, exchanges, mail order and sales – all completely new concepts at the time – attracted customers in their droves.

The brainchild of Aristide Boucicaut, a former fabric merchant who saw an opportunity for a new kind of establishment which offered customers more choice, Le Bon Marché began life as a small novelty shop on the corner of rue du Bac and rue de Sèvres. Its phenomenal success meant that by 1888 the store occupied an entire block.

1898: Street Musicians, Paris

This evocative image of musicians on a street in Paris was taken by Atget shortly after he began his project to document 'Old Paris'. He was inspired by the disappearance of many older buildings in the wake of the sweeping modernisation of the city, which had begun under Baron Haussmann in the 1850s.

Atget set out to record the character and detail of areas largely untouched by the glamour of the Belle Époque. In doing so he created some of the most original and iconic images of the age.

1899: Children at a Guignol performance, Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris

Created in Lyon by the puppeteer Laurent Mourget during the early 19th century, the character of Guignol has become an integral part of French culture, captivating children and adults alike.

With stories and dialect drawing on the working class culture of his native city, Mourget created a whole cast of characters including Guignol’s friend Gnafron, his wife Madelon and Flageolet the gendarme. Permanent Guignol theatres have been a fixture in Paris since the 19th century, such as the one Atget captured here in the Jardin du Luxembourg.

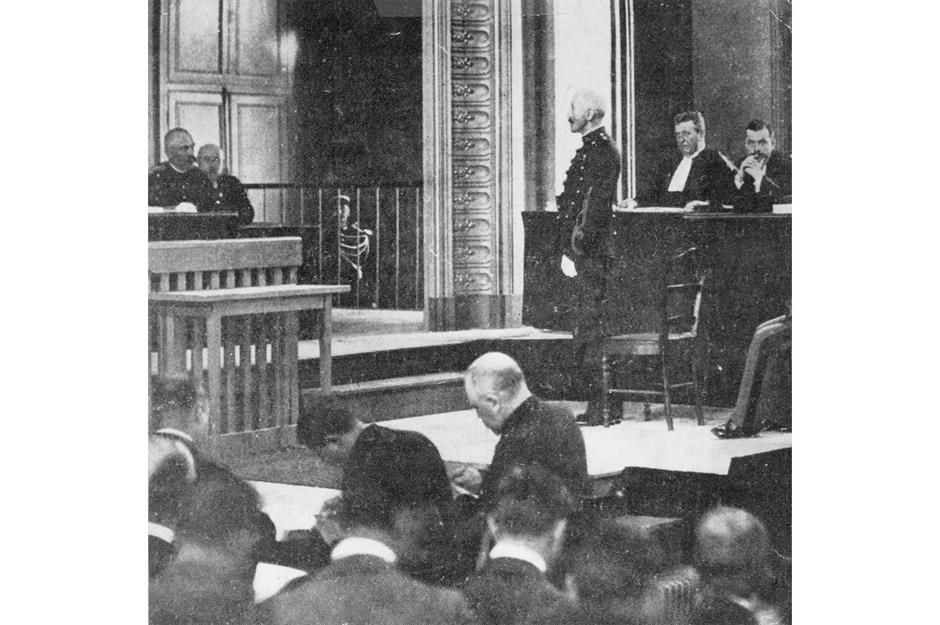

1899: Court Martial of Alfred Dreyfus, Rennes

One of the most famous miscarriages of justice in history, the Dreyfus Affair polarised political opinion in France and came to symbolise the injustice and antisemitism concealed beneath the veneer of respectable society. In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery officer of Jewish descent, was wrongfully convicted of selling French military secrets to the Germans.

When the true culprit, a French Army Major, was revealed, high ranking military officials forged evidence to ensure that Dreyfus’ conviction stood. A second court martial in 1899 also found him guilty, but French President Émile Loubet pardoned him to defuse public outrage. Dreyfus was not exonerated until 1906, following years of public pressure.

1899: Claude Monet in his garden at Giverny

The garden of Claude Monet’s house at Giverny would be the famous artist’s greatest source of inspiration for more than 40 years, its iconic Japanese bridge and water lily pond providing the subject for some of the most famous Impressionist paintings ever created.

Monet moved into the house in 1883, and soon began to develop the surrounding land, employing a small army of gardeners to create a glorious natural environment overflowing with beautiful perspectives, reflections and colours. He would recreate these in his stunning canvases, painting the water lily pond alone more than 250 times. But he would later reflect that, 'my greatest masterpiece is my garden'.

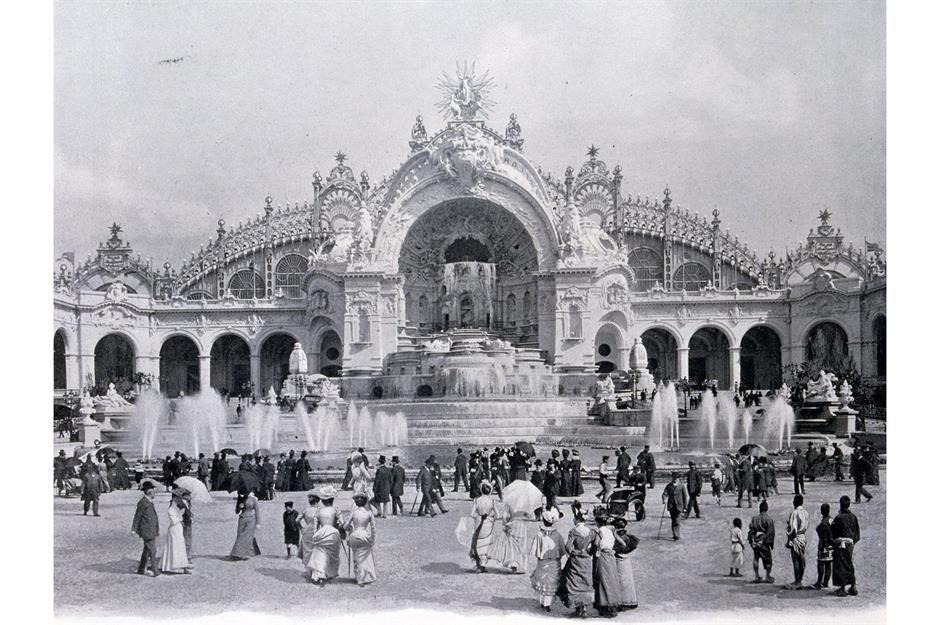

1900: Exposition Universelle, Paris

The 19th century drew to a close with Paris’s largest World’s Fair to date, designed to celebrate the achievements of the past 100 years and give a glimpse of the innovations which would shape the next. Enduring monuments such as the Grand Palais and Petit Palais were built especially for the occasion, while the Eiffel Tower was repainted yellow and fitted with 7,000 electric lamps.

Among the many wonders on display were early escalators, diesel engines, talking pictures and even an electric car. The Palais de l’électricité (pictured) was a major attraction. Entirely lit and decorated with electric bulbs it shone a dazzling light into the future.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature