The most incredible archaeological discovery found in your state

America's history, unearthed

From historic shipwrecks and phenomenal fossils to mysterious petroglyphs and ancient human settlements, America isn’t short of fascinating archaeological sites and artifacts. We’ve tracked down the most incredible find in every state.

Read on to discover the archaeological wonder found in your state…

Alabama: Moundville Archaeological Park

Moundville Archaeological Park, situated on the banks of the Black Warrior River, contains the remains of one of the largest prehistoric Native American settlements in the United States. Occupied from around AD 1000 to 1450, the site was once home to a 300-acre village. It was first mapped in 1869, with the first scientific excavations beginning in 1929.

From 1933 to 1941, 2,000 burials, 75 house remains, and thousands of artifacts were discovered. To date, only 14% of the site has been excavated. The development, sociopolitical organization, and reasons for the eventual abandonment of the site remain a mystery.

Alaska: Nunalleq archaeological site

At the archaeological site of Nunalleq, on the southwest coast of Alaska, archaeologists have unearthed the remnants of a bloody 17th century massacre. It was once home to around 50 members of an early Yupik (Alaskan Native) community who were likely attacked by a neighboring community around 1660, during the Little Ice Age, when food was scarce and bitterly fought over.

Skeletons of elders, women, and children suggest that no one was spared. However, not all the finds have been so macabre. Since 2009, the site has yielded more than 2,500 fascinating artifacts, including ritual masks, carved dolls, and bentwood bowls (pictured).

Arizona: Split-twig figurines, Grand Canyon

Numerous artifacts have been discovered in the Grand Canyon, revealing a human presence dating back some 12,000 years. Some of the most fascinating discoveries made here are the split-twig animal figurines that have been found in remote caves. Dating back between 2,000 and 4,000 years, they are often in the shape of deer or bighorn sheep and are sometimes pierced with another stick resembling a spear.

The first examples were discovered in 1933 and while their exact function remains a mystery, recent research has suggested that they were totems associated with the Late Archaic hunting and gathering culture.

Arkansas: Head pots

Head pots are an extremely rare and unique form of prehistoric Native American pottery. Created between AD 1400 and 1700, they're found almost exclusively in northeast Arkansas and the neighboring Bootheel region of Missouri. Crafted to suggest a person in death, the eyes are closed and the sculpted facial tissue appears to have dried and retracted, exposing the teeth.

A head pot was first excavated in 1880 at an archaeological site in Cross County. This example (pictured) was discovered at the Nodena site on the Mississippi River in what is now Mississippi County.

California: Blythe Intaglios, Colorado Desert

As impressive as they are mysterious, the Blythe Intaglios are a group of enormous geoglyphs (or ground drawings) incised into the arid earth of the Colorado Desert. Depicting a mixture of animals, geometric shapes, and human figures, the largest of them is 171 feet long.

Between 450 and 2,000 years old, no one knows exactly what their original purpose was, although they seem to relate to Native American creation myths. So large that they are all but impossible to see at ground level, these geoglyphs escaped the notice of non-native eyes until 1932 when they were spotted by a pilot flying between Blythe and Las Vegas.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for more travel and history stories

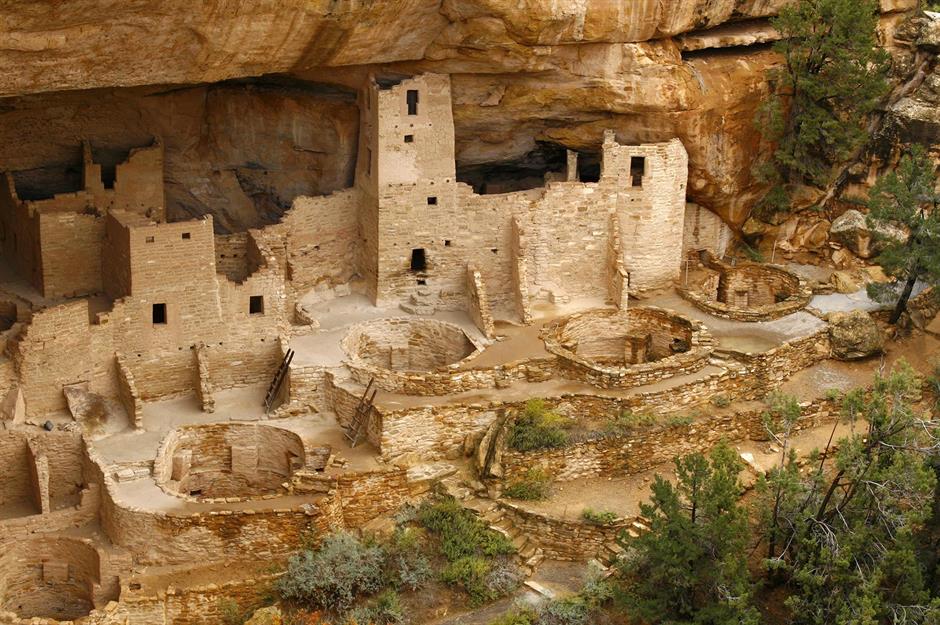

Colorado: Cliff Palace

Cliff Palace is one of the finest examples of a late prehistoric cliff dwelling in the American Southwest. Built between AD 1190 and 1260, it contained 150 rooms and 23 kivas (subterranean ceremonial and social chambers) and housed around 100 people.

Abandoned by 1300, it slowly deteriorated over the centuries. Its rediscovery by ranchers in 1888 only hastened its decline, with commercial explorers using everything from pickaxes to dynamite to recover artifacts. The establishment of Mesa Verde National Park in 1906 began a process of preservation, although ongoing deterioration and unpredictable foundations makes the task a challenging one.

Connecticut: Barkhamsted Lighthouse site

According to legend, Barkhamsted Lighthouse was given its name by stagecoach drivers who used the settlement’s lights for guidance. It was home to a humble, ethnically diverse community of Native American, European, and African descent who lived a relatively isolated life here from the mid-18th century to 1860.

Excavations in 1986, 1990, 1991, and 2009 uncovered the remnants of structures, quarries, and a cemetery consisting of unmarked stones (pictured). Recognizing the importance of a site which tells the story of those often neglected in American history, Barkhamsted Lighthouse was made a State Archaeological Preserve in 2008.

Delaware: Burial ground, John Dickinson Plantation

The John Dickinson Plantation is the boyhood home of John Dickinson, a Founding Father of the United States and one of the signatories of the US Constitution. Although Dickinson was ostensibly a believer in the abolition of slavery, he still used enslaved labor on his plantation.

In 2021, after two years of archaeological investigations, a burial ground for those enslaved here was uncovered. The Department of State, Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs is now consulting with descendant communities on how best to commemorate this significant site.

Florida: Windover Archaeological Site

When human remains were first discovered in a pond near Titusville, Florida, in 1982, no-one expected that they would turn out to be one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Further exploration of the Windover Site (named for a nearby housing development) revealed the remains of no less than 168 skeletons, all dating back more than 7,000 years, pre-dating even the Egyptian pyramids.

Well-preserved due to the peat in which they had lain for millennia, many of the skulls even contained intact brain tissue. Archaeologists also recovered numerous wooden artifacts, textiles, and tools which provided invaluable information about life, death, and burial practices in prehistoric times.

Georgia: Dyar Mound, Lake Oconee

Built in the 14th century by the ancestors of today’s Muscogee Creek people, Dyar Mound now lies beneath Lake Oconee, a reservoir created by a dam in the 1970s. Excavations at the time led archaeologists to believe that Dyar Mound had been abandoned shortly after a 1539–1543 expedition led by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, which had brought diseases that decimated the local population.

However, recent research has shown that the Muscogee carried out rites connected to their Mississippian belief system on the mound for almost 150 years after that date, meaning that the expedition did not precipitate the end of that tradition as previously thought.

Hawaii: South Point Complex

The South Point Complex is thought to be the site of one of the earliest settlements in the Hawaiian Islands and the landing place of Hawaii's very first inhabitants. In 1956, the remains of one of the oldest known Hawaiian dwellings was uncovered at the Pu'u Ali'i (Hill of Chiefs) by archaeologists from the Bishop Museum.

More than 14,000 artifacts, including over 60 different types of large fishhooks, were also excavated. Ancient Hawaiians fished from canoes and centuries-old mooring holes can be seen in the rocks to the west of the Kalalea Heiau (pictured).

Idaho: Spears at Cooper's Ferry

Discoveries at the Cooper’s Ferry site have yielded important insights into some of the earliest humans that inhabited America, some 16,000 years ago. The spear points unearthed here in 2022 are particularly notable. At roughly 15,700 years old, they are 3,000 years older than the Clovis points found throughout North America.

Their similarity to points found in Hokkaido, Japan, dating back 16,000 to 20,000 years, supports the idea that there are early genetic and cultural connections between the ice age peoples of Northeast Asia and North America, who likely shared their technological knowledge.

Illinois: Cahokia

Constructed around the year AD 1000, Cahokia is thought to have been the largest and most cosmopolitan city north of Mexico. Incredibly, it was laid out to a specific plan from the outset, revealing a sophisticated sense of design. By 1350 though, it had been deserted by its native inhabitants, the Mississippians.

The reasons for its demise remain a mystery but excavations since the 1960s have revealed fascinating insights into life in the city. Stone and ceramic figurines together with a small copper workshop reveal a creative side, while on a more macabre level a mass burial mound suggests that the Mississippians conducted ritual human sacrifices.

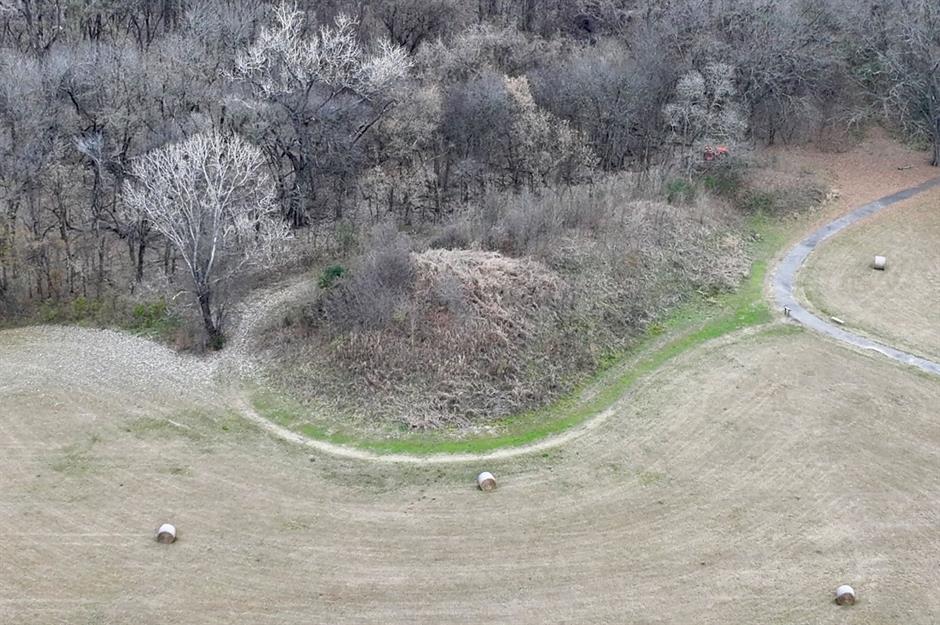

Indiana: Angel Mounds

Angel Mounds is one of the best preserved Mississippian culture sites in the US and remains a sacred site for today’s tribal nations. The site contains 11 earthen mounds, constructed to elevate important buildings in a city that existed between 1100 and 1450, and became a major center by around 1250.

Between 1939 and 1964, more than 2.5 million artifacts were excavated from the site. The excavations led to the discovery that the Mississippian culture was the first to have an extensive agricultural society as well as build permanent communities.

Iowa: Effigy Mounds

Beautifully situated in one of the most picturesque areas of the Upper Mississippi Valley, Effigy Mounds National Monument preserves more than 200 prehistoric earthworks built by early Native Americans. Many are conical or rectangular shapes, serving as ceremonial or burial sites, but others represent specific animals such as birds, bears, deer, and bison.

The product of Pre-Columbian Mound Builder cultures, these mysterious forms date from between 1400-750 BC and still retain sacred significance for the area’s Native American tribes. Today, a visitors’ center in the park displays archaeological artifacts and natural specimens relating to these intriguing structures.

Kansas: Etzanoa

First mentioned by Spanish Conquistadors at the start of the 17th century, the city of Etzanoa was once a vast Native American settlement and trading post, home to some 20,000 people. It flourished between 1450 and 1700 before disappearing from the face of the earth, most likely wiped out by disease brought by European colonists. In recent years, however, this 'lost city' has begun to re-emerge.

Digs near present-day Arkansas City and Walnut River have yielded thousands of artifacts, giving a fascinating glimpse into one of the largest prehistoric Native American towns in the US. Excavations are ongoing, but a visitors' center is planned for the near future. Pictured, archaeologist and anthropologist Donald Blakeslee points out man-made depressions on a boulder in what was once Etzanoa.

Kentucky: Red Bird petroglyphs

Featuring a series of petroglyphs which defy interpretation, the Red Bird Stone in Kentucky’s Clay County has been a mystery for as long as anyone can remember. Some insist they were made by the Cherokee chief Red Bird (after whom the nearby river is named), while others claim they were made by pre-Columbian explorers from Europe, the Middle East or North Africa.

In 1994, the enormous stone, measuring 22 feet long and weighing 45 tonnes, fell onto an adjacent road and was moved to a park in nearby Manchester, where it is now on permanent display.

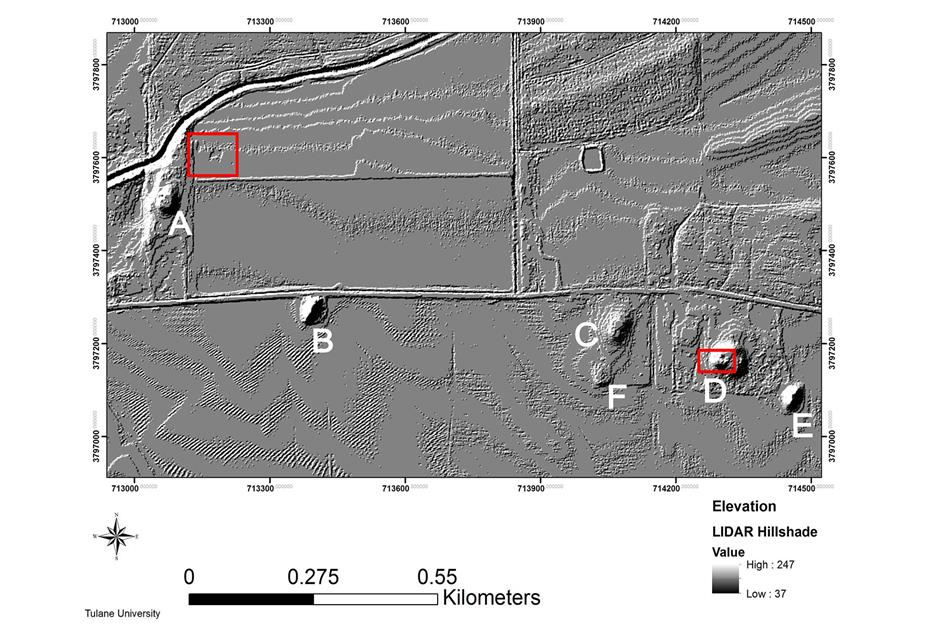

Louisiana: Poverty Point World Heritage Site

Poverty Point is a truly astonishing series of earthworks that include a massive 72-foot-tall mound and enormous concentric half circles. Built entirely by hand between around 1700 BC and 1100 BC, when it was abandoned, it dwarfed every other comparable site for 2,200 years.

When they were first reported in 1873, the mounds were thought to be natural formations. It was only when they were viewed from above in the 1950s that archaeologists realized they were manmade. Artifacts and stones from up to 800 miles away have led to speculation that the site was an ancient residential, trade, and ceremonial center.

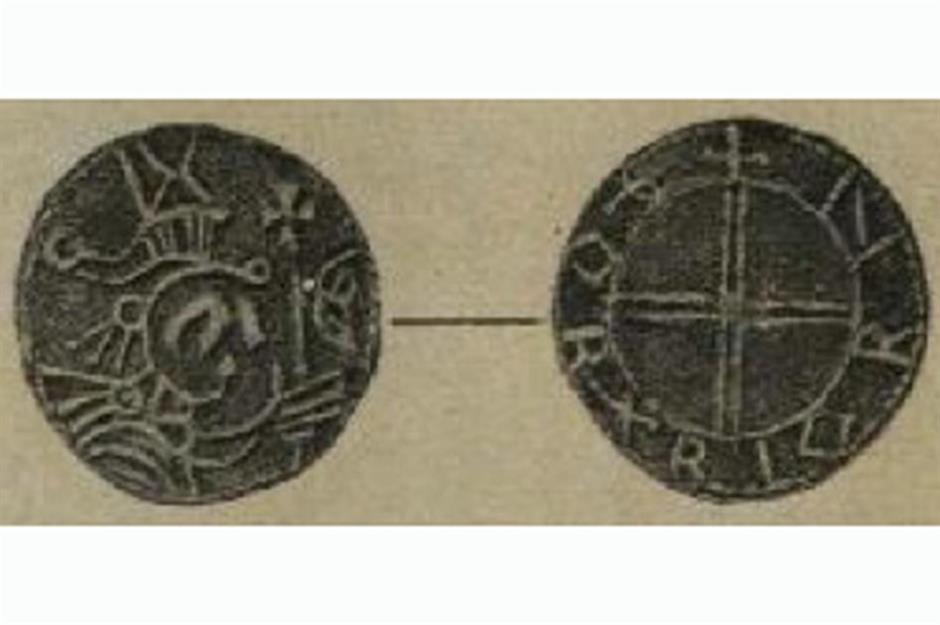

Maine: The Maine Penny

Is it possible that a small silver coin could prove that the Vikings discovered America before Columbus? Some claimed this was the case after the Maine Penny was unearthed in 1957 on Naskeag Point near Brooklin on the coast of Maine. Others, however, were convinced that it was placed there as a hoax.

The coin, which dates from the reign of Olaf Kyrre, King of Norway from AD 1067 to 1093, is undoubtedly genuine. Detailed analysis in the years since has shown that it had lain in the same position beneath the earth for centuries before being discovered. But to this day no-one really knows how it got there, and the mystery of the Maine Penny remains unresolved.

Maryland: St Mary’s Fort, St Mary’s City

When it was finally discovered in 2019, archaeologists had been searching for the remains of St Mary’s Fort, built in 1634 by the first English colonists to reach the western side of the Chesapeake Bay, for over 90 years. The site, about half a mile from St Mary’s River, had been excavated over 200 times in the previous 30 years but nothing conclusive had been found.

The breakthrough came thanks to the use of magnetic susceptibility, magnetometry, and ground-penetrating radar to survey the site. Scans revealed the contours of the historic structure, as well as the imprints of postholes.

Massachusetts: Dighton Rock

The Dighton Rock is a mysterious 40-ton boulder, covered in petroglyphs, that once sat beside the Taunton River near the town of Dighton. Now displayed in a museum in Dighton Rock State Park, it was first noted by recent Harvard graduate John Danforth in 1680 and has fascinated scholars and the public ever since.

Over time, the rock’s markings have been ascribed to a bizarre cast of characters – Norsemen, Egyptians, the Lost Tribes of Israel, vanished Portuguese explorers, a prince from Atlantis, and, of course, aliens. Danforth himself thought they were the work of Native Americans, but conclusive proof has still to be found.

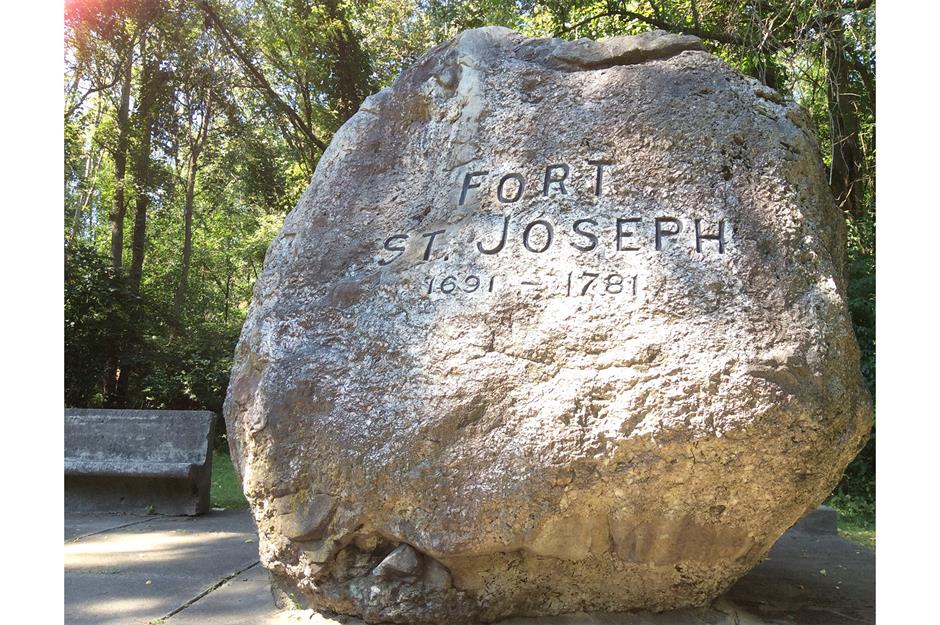

Michigan: Fort St Joseph site

Although Fort St Joseph was abandoned in 1781, it was never forgotten by the residents of Niles. A commemorative granite boulder was placed near where it was thought to have stood in 1913 (pictured).

Collectors in the late 19th and early 20th century had recovered artifacts in the vicinity. However, it wasn’t until 1998 that a full archaeological survey was carried out, leading to the discovery of the fort’s site on the east bank of the river in Niles. Subsequent excavations have been challenging due to the site being submerged for much of the year.

Minnesota: Fur trade artifacts, Grand Portage National Monument

The French and British fur trade thrived in Minnesota between 1680 and 1816, and the Grand Portage trail, part of an ancient transcontinental trade route connecting the Great Lakes to the interior of the continent, played a vital role in this.

During the 1920s, archaeologists were able to map the remains of Fort Charlotte on the Pigeon River, once a Northwest Depot for North canoes laden with furs collected over the winter. Further underwater excavations in the 1960s and early 1970s led to the discovery of thousands of well-preserved fur trade artifacts.

See how we've ranked the best historic attraction in every US state

Mississippi: Carson Site

In 2007, a planned farming operation at what's now known as the Carson Site uncovered evidence of a once large Native American village. Further excavations between 2012 and 2015 uncovered the site’s first artifacts.

Research has shown that the site was first occupied by Native Americans from the St. Louis region, who migrated downriver and established a settlement. Over the following centuries, they built earthen mounds, constructed a village, and began harvesting corn.

Missouri: Shoes, Arnold Research Caves

From the 1950s onwards, dozens of pairs of prehistoric shoes have been excavated from the Arnold Research Cave, including leather moccasins and sandals made from rattlesnake master. As fibrous materials are perishable and decompose relatively quickly, such finds are rare.

The shoes owe their survival due to the Arnold Research Cave being one of the few dry caves in Missouri. Its constant temperature and humidity levels have prevented the shoes, some of which date back an astonishing 8,000 years, from decomposing.

Montana: Anzick Site

The Anzick site is the only known Clovis burial site. Back in 1968, construction workers stumbled across the skull of a young child together with more than 100 artifacts at the Anzick family's land near Wilsall. Among the discoveries, they found Clovis spear points as well as various tools made from stone and bone.

In 2014, Sarah Anzick – two years old at the time of the discovery – was involved in DNA sequencing that suggests the Clovis child is the ancestor of today's native peoples from Central and South America. If correct, these findings refute the idea that migrants from Western Europe founded the Clovis culture.

Nebraska: Engineer Cantonment

Engineer Cantonment was the winter quarters of the 1819-20 Stephen Long Expedition, notable for being the first time the US government sent a team of trained scientists and artists on a mission to study a region’s plant and animal life. The team discovered numerous ‘new’ species including the coyote.

Lost for over 200 years, the site was rediscovered in 2003 with the help of old paintings and test excavations. During the ensuing search, archaeologists uncovered numerous artifacts including broken china, trade beads, and gun flints. They also found the foundations of one of the buildings where the men spent the winter.

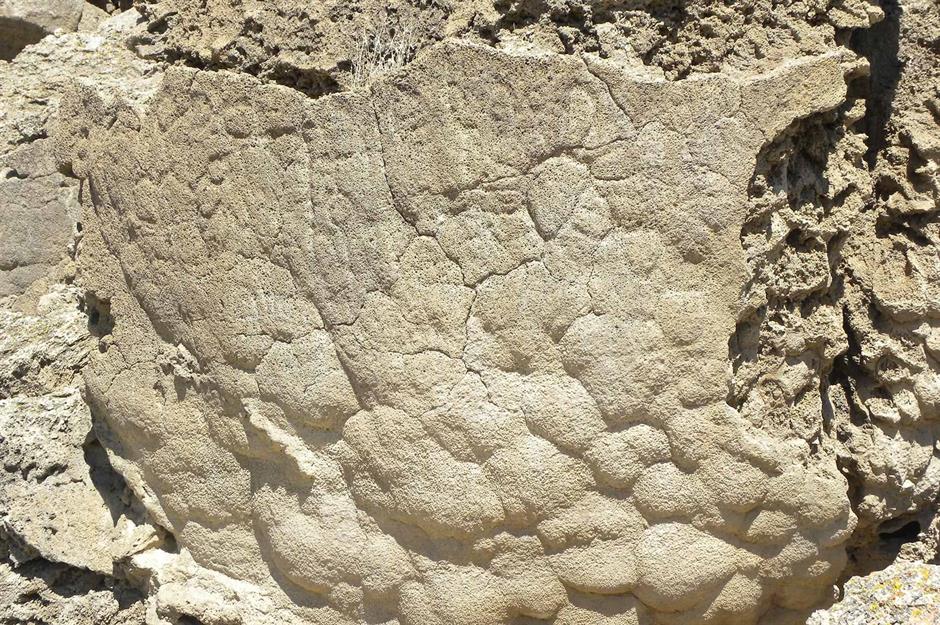

Nevada: Winnemucca Lake petroglyphs

Since the nearby Derby Dam was built in 1903, Winnemucca Lake in northwest Nevada has been little more than a dry lakebed. But the surrounding area is home to a series of remarkable petroglyphs (rock carvings) which, in 2013, were declared by researchers to be the oldest in North America. They date from 10,500 to 14,800 years ago.

The exact meaning of these carvings, deeply engraved into limestone boulders, remains unknown. Some are abstract designs, suggesting clouds or lightning, while others resemble trees or leaves. Unfortunately, access to the site, part of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribal Reservation, is now restricted due to vandalism.

New Hampshire: Lake Winnipesaukee mystery stone

A puzzle to archaeologists for more than 150 years, the Lake Winnipesaukee Mystery Stone is aptly named. Discovered in 1872 by workers digging a fence post in Meredith, New Hampshire, this small egg-shaped object is around four inches tall and just under three inches wide. Strangely, it's made of quartzite, a type of rock not found in New Hampshire.

Its surface is perfectly smooth except for a number of enigmatic carvings, possibly machine-tooled, including a face, an ear of corn, and other more abstract shapes. Now on display in the Museum of New Hampshire History, its true nature still eludes scholars. Some think it’s a prehistoric Native American artifact, others a lodestone, or even evidence of aliens.

New Jersey: 1796 archives

A surprising discovery awaited construction workers in Trenton, New Jersey, when, in 2006, they were taking up the sidewalk in front of its historic State House (pictured). These routine excavations revealed the long-hidden foundations of the original building constructed to house the state’s archives.

Built in 1796, the structure included specially designed fireproof vaults to preserve the state’s most valuable Revolutionary and Colonial era documents, which now form the core collection of the modern state archives. The building was buried when the State House was expanded half a century later. Its outline is now marked by a series of special stones.

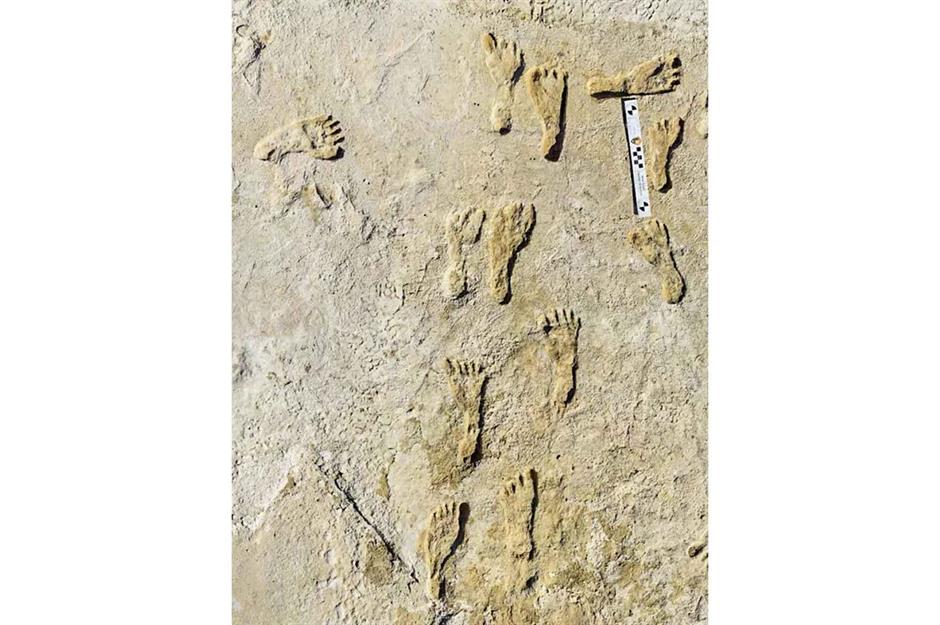

New Mexico: Fossilized footprints, White Sands National Park

Once a land of enormous lakes, streams, and grasslands, White Sands National Park is now a vast expanse of gypsum dune fields. It was here, in 2009, that scientists discovered a remarkable collection of fossilized footprints which are among the oldest evidence of human life in the Americas.

Researchers have estimated the prints to be around 23,000 years old. If accurate, this rewrites history, as it was previously thought that humans arrived in North America no more than 13,500 to 16,000 years ago. Casts of these fascinating footsteps are on display in the park’s visitor center.

New York: Lamoka Lake artifacts

First excavated in the 1920s, the Lamoka Lake Site in Schuyler County, New York, is of key importance as it provided the first definitive evidence of an Archaic hunter-gathering culture in the northeastern United States. Artifacts recovered from the site reveal that it had been inhabited as far back as 3,500 BC.

As well as numerous projectile points, mortars and pestles, and tools made from animal bones, archaeologists discovered fascinating evidence of established human settlements, including hearths, fire-beds, burial sites, and lodge floors which might once have belonged to small houses.

North Carolina: First Colony artifacts

In 1587, the first permanent English colony in the New World was founded on North Carolina’s Roanoke Island. However, when John White, the newly appointed governor of the fledgling colony, returned from England with supplies in 1590, he found it looted and abandoned.

What happened there has remained a mystery ever since. In 2015, archaeologists recovered European objects including a sword hilt and broken English bowls on Hatteras Island and another mainland site, both 50 miles away, which suggests that the colonists may have split into two camps and assimilated with Native Americans. Not everyone is convinced, however, and for now the search continues.

North Dakota: Teen Rex

In the summer of 2022, two young boys out hiking with their father and cousin spotted some large bones poking out of a rock. Having no idea what they were, their father took some pics and sent them to a friend, the curator of paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. It turned out they had stumbled upon the skeleton of a rare young Tyrannosaurus rex.

According to the museum, where the skeleton now resides, only a few such fossils have been discovered worldwide. The discovery will enable researchers to study how these fearsome beasts matured.

Ohio: Serpent Mound Historical Site

Measuring over 1,348 feet long, the Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio, is the world’s largest documented example of a prehistoric effigy mound. This enormous earthen embankment, in the form of a snake with a curled tail, was built by Native Ohioans, although its exact origins remain uncertain.

Archaeological digs in the 19th century revealed no artifacts which would date it accurately, but the presence of nearby burial mounds suggested it was built by the Adena Culture somewhere between 800 BC and AD 100. However, more recent radiocarbon dating suggests it was a creation of the Fort Ancient Culture around AD 1120.

Oklahoma: Spiro Mounds

Between 1933 and 1935, commercial diggers haphazardly excavated the burial mound at the previously largely undisturbed Spiro Mounds site. Consisting of 12 mounds built by the Mississippians between 850 and 1450, the spot yielded a stunning array of artifacts. What's more, these artifacts were in better condition and showed more sophisticated decoration than those found at any other Mississippian site.

They were sold around the world and now reside in more than 65 museums across the US, Europe, and Asia. It remains the worst looting of an archaeological site in US history. Thankfully, Spiro Mounds is now a protected site administered by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Oregon: Rimrock Draw Rockshelter site

Rimrock Draw Rockshelter Site, an ancient natural shelter used by Paleoindian peoples, has been excavated by archaeologists since 2011. Discoveries have included stone tools and tooth fragments from Pleistocene mammals.

Most exciting of all, however, was a pair of finely crafted orange agate scrapers which radiocarbon dating has placed 18,250 years ago, suggesting that this is one of the oldest sites of human occupation ever found in North America.

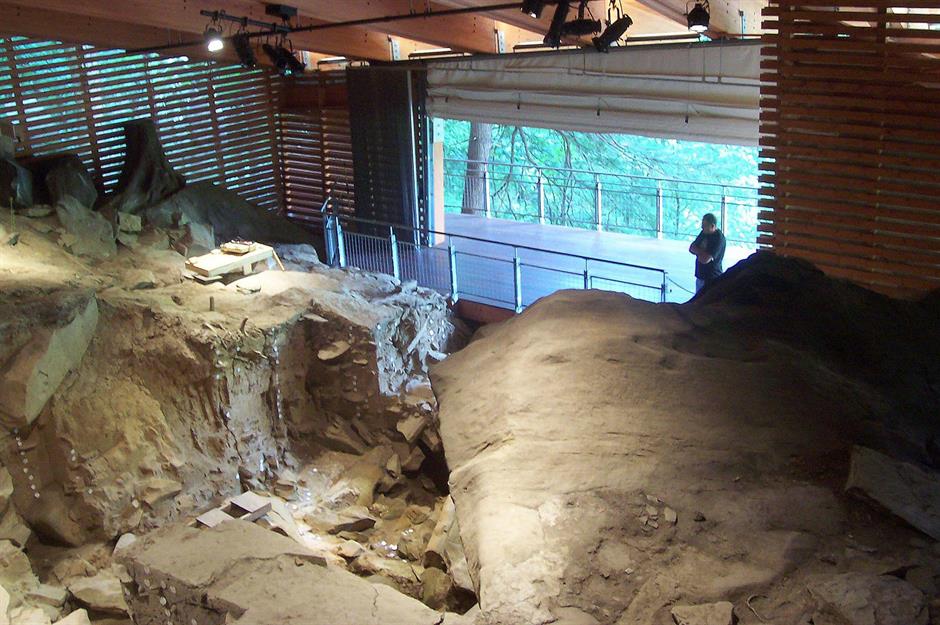

Pennsylvania: Meadowcroft Rockshelter

In 1955, Albert Miller stumbled across what looked like a prehistoric tool in a gopher hole on his family farm in Avella. It would be the first of almost two million artifacts unearthed at Meadowcroft Rockshelter, a large rock ledge overhang used as a shelter during the Paleoindian period.

One of the most important archaeological sites ever discovered in America, it has yielded artifacts which date back almost 19,000 years. This means it's one of the oldest sites of human habitation in the New World. Today, it is part of Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center and open between May and October.

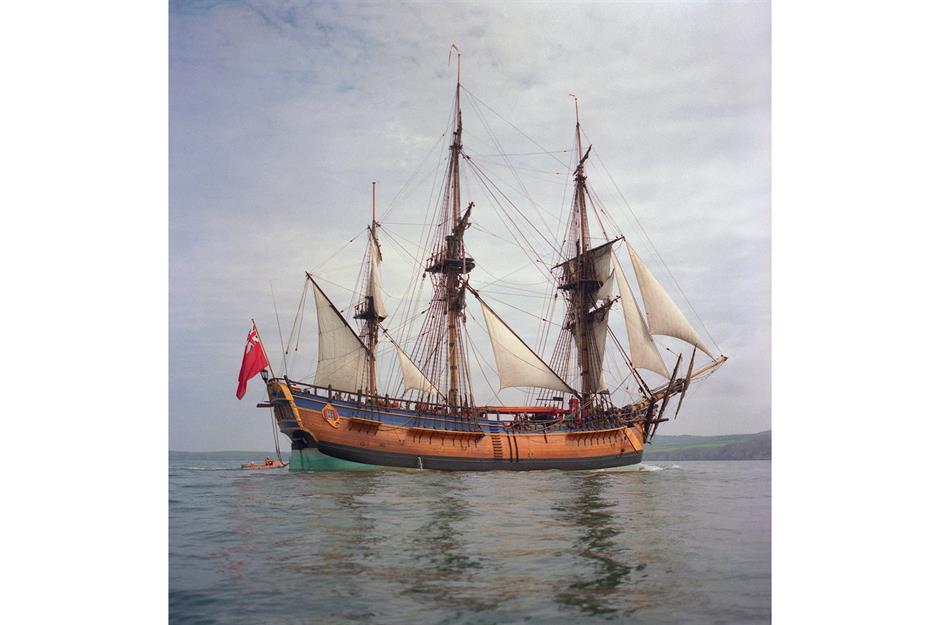

Rhode Island: HMS Endeavour

In 2022, a group of maritime archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum declared that a wreck they had been studying since the 1990s was that of Captain Cook’s HMS Endeavour (pictured is a replica), a ship in which he famously explored the South Pacific. And the evidence certainly seems to stack up.

The wreck lies in Newport Harbor, where it's known Cook’s ship was sunk, and the length of a large section of it is an almost perfect match with dimensions shown on historic Royal Navy plans for Endeavour. However, the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project, which has been working with the Australians, is not yet 100% convinced.

South Carolina: Topper Site

Since it was first excavated in 1985, the Topper Site, located along the Savannah River in Allendale County, South Carolina, has yielded artifacts which some archaeologists believe may predate the Clovis period (c.13,050-12,750 ago) by up to three millennia. More controversially, Albert Goodyear of the University of South Carolina has claimed that burnt material from a prehistoric charcoal fire discovered deep under the ground may prove that humans occupied the site as far back as 50,000 years ago.

If true, this would radically rewrite history, although the claim has been disputed by other scientists.

South Dakota: Sue T-Rex skeleton

One of the star attractions at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, 'Sue' is among the largest, most complete, and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus rex fossils ever discovered. It was named after Sue Hendrickson, the fossil collector and explorer who unearthed her in 1990.

An astonishing 13 feet tall at the hips and more than 40 feet long, Sue is an impressive sight and lived to about 28 years – about as old as a T-rex can get. Purchased by the Field Museum in 1997 for $8.4 million, it became the most expensive fossil ever sold at auction.

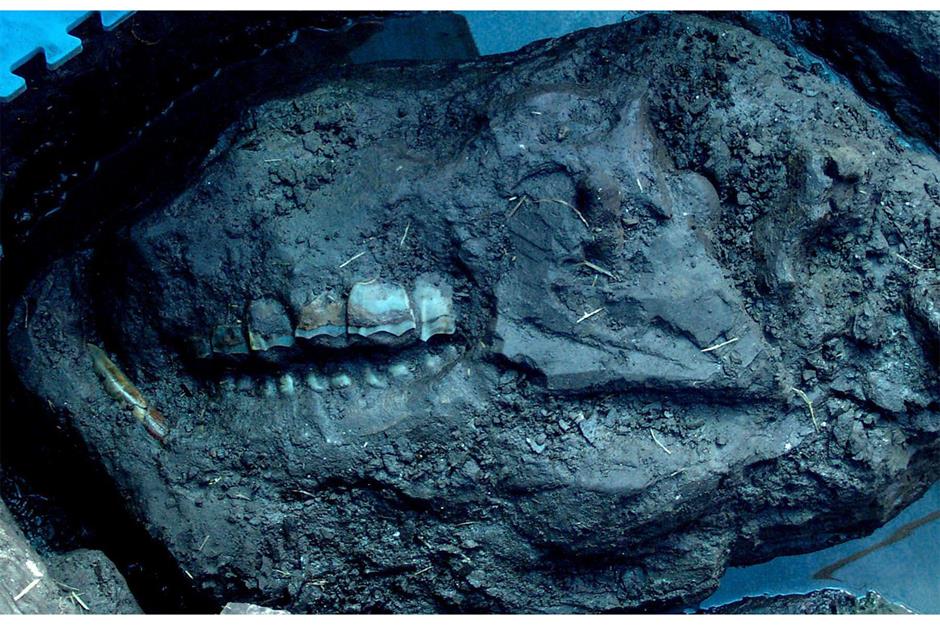

Tennessee: Gray Fossil Site

What is now known as the Gray Fossil Site was once a forested pond ecosystem that flourished almost five million years ago during the Early Pliocene Epoch. It was discovered during a road building project in 2000 and proved to be so unique that construction was moved elsewhere.

Excavations here have unearthed the fossils of around 200 species of animals and plants buried in an ancient sinkhole-pond. These fossils reveal that the forest was filled with oak, hickory, and pine trees and home to tapirs, rhinos (pictured), alligators, mastodons, and more. Visitors are able to tour the site and adjacent museum.

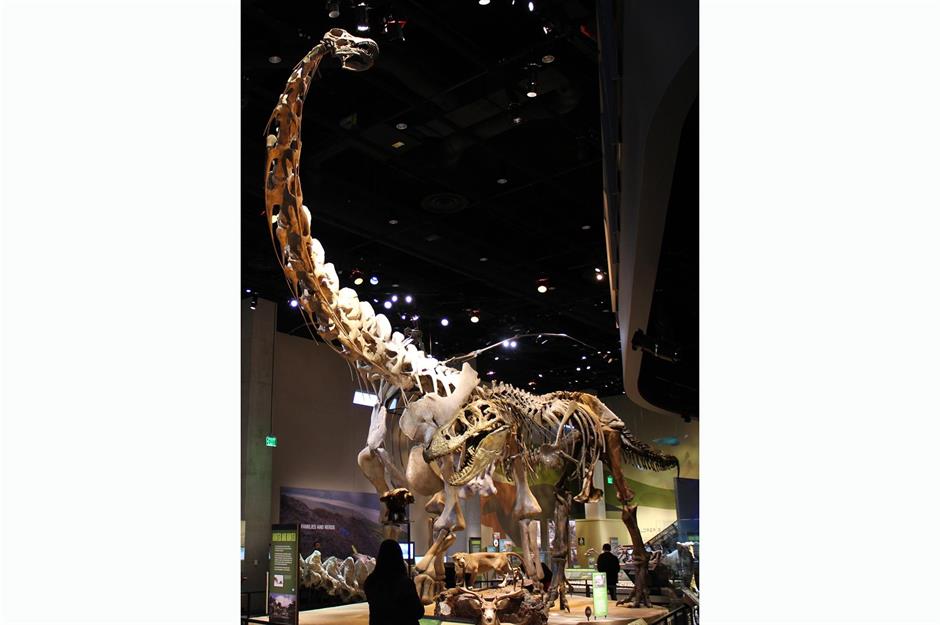

Texas: Alamosaurus, Big Bend National Park

When dinosaur bones were discovered in Big Bend National Park in 1999, they were so enormous that they were impossible to remove by hand and had to be transported by helicopter. The bones belonged to an Alamosaurus – a large herbivore with a long neck and tail – which would have measured 100 feet in length and weighed around 50 tons.

They first appeared in North America around 70 million years ago, possibly migrating from South America when the two continents joined. The bones now form the basis of a restored Alamosaurus skeleton at the Perot Museum in Dallas (pictured).

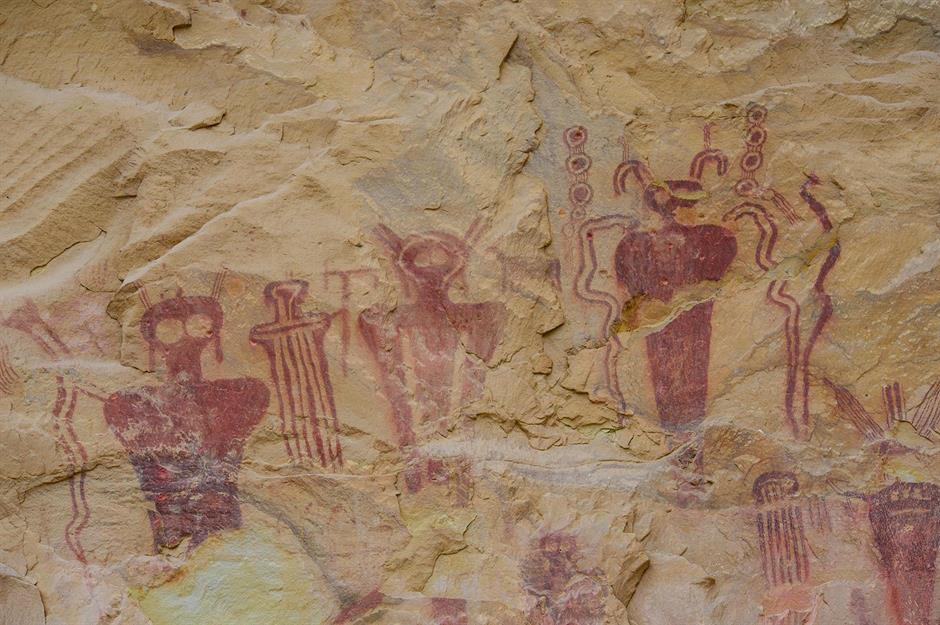

Utah: Horseshoe Canyon rock art

The network of sheer sandstone walls which make up Horseshoe Canyon are home to some of the most impressive rock art in North America, with numerous pictographs (painted figures) and petroglyphs (etched in the rock’s surface) dotted throughout its passages. Most date from the Late Archaic period, (2000 BC to 500 BC), when nomadic hunter-gatherers would make the area their seasonal home.

Today, these ghostly life-size figures, often simple silhouettes without arms or legs, form a potent reminder of the creativity of ancient Native American cultures.

Vermont: Gunboat Philadelphia

Built for Benedict Arnold in 1776, and sunk in Lake Champlain that same year during the Battle of Valcour Island, the gunboat Philadelphia was eventually recovered in 1935 by Colonel Lorenzo Hagglund, who displayed it for many years as a roadside attraction in rural New York state.

The 54-foot vessel was bequeathed to the Smithsonian by Hagglund’s widow in 1961, complete with the cannonball that sank it. Currently undergoing conservation work, the boat will be back on display in 2026 in time for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Virginia: Cactus Hill Archaeological Site

For many years it was widely believed that the first humans to inhabit North America were the Clovis people, around 13,000 years ago. However, recent discoveries are challenging that idea, with a number of sites offering evidence of pre-Clovis occupation dating back much further.

Named for the prickly-pear cacti which grow in its vicinity, Cactus Hill is perhaps the oldest of these fascinating sites. During the 1990s, archaeologists discovered evidence of a much older habitation below a Clovis-era settlement, including stone tools and hearths, which date back to between 18,000 and 20,000 years ago.

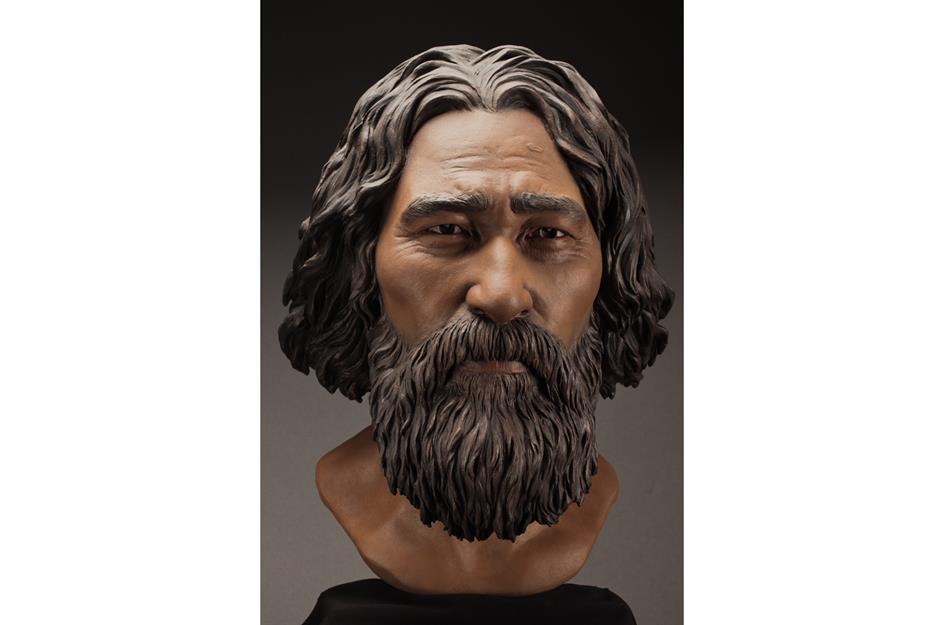

Washington: Kennewick Man

In 1996, two college students stumbled upon a human skull in Columbia River. When the rest of the almost complete skeleton was found nearby and examined by scientists, it was revealed that 'Kennewick Man' was almost 9,000 years old – an ancestor of modern Native Americans.

The discovery sparked a 20-year legal battle between the scientific community, the Federal government (who owned the land where it was found), and Native Americans about who had legal rights over the remains. After being stored at the University of Washington’s Burke Museum for many years, the ancient bones were finally allowed a traditional burial in 2017. Pictured here is a facial reconstruction of what the man might have looked like.

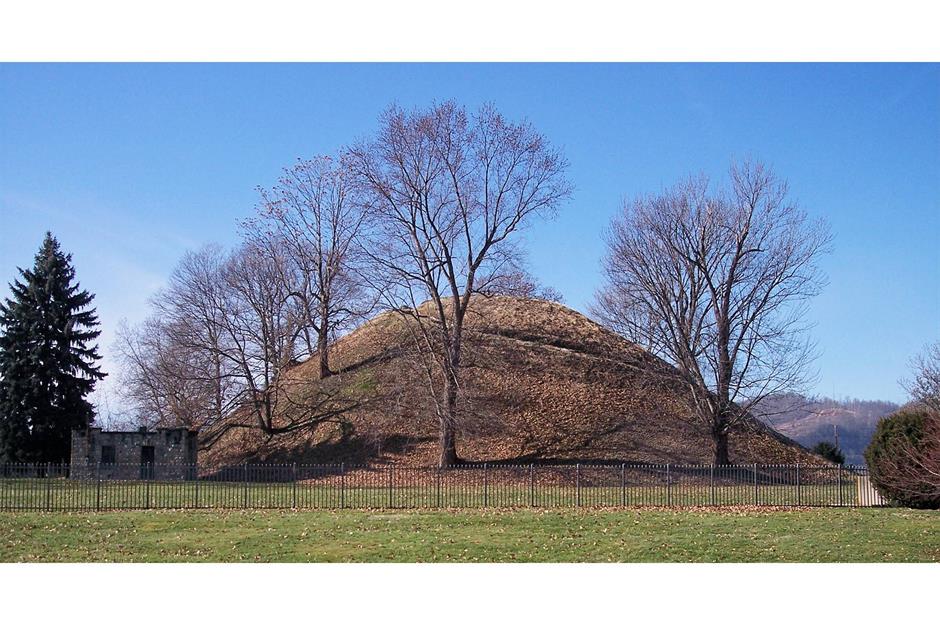

West Virginia: Grave Creek Mound

The largest conical burial mound in the United States, Grave Creek Mound, was built between 250 and 150 BC by prehistoric Native Americans known as the Adena. Standing 62 feet high and 240 feet wide, its construction was a massive undertaking, involving the movement of around 60,000 tons of earth and sand.

Since the earliest excavations in 1838, the mound has been a major landmark and tourist attraction. During the 19th century, it even had a saloon on its summit and a racetrack around its perimeter. Today, an extensive array of artifacts can be viewed at the Grave Creek Archaeological Complex.

Wisconsin: Dugout canoe, Lake Mendota

In 2021 and 2022, the Wisconsin Historical Society, in association with the state’s Native Nations, recovered a pair of ancient dugout canoes from Lake Mendota. The first was 1,200 years old, while the second was 3,000.

If that wasn’t impressive enough, in May 2024 it was announced that remains of 11 canoes had been identified in total, one of which dated back 4,500 years – the oldest ever recovered in the Great Lakes. Currently undergoing a lengthy preservation process, the two original canoes will eventually be displayed in the new Wisconsin History Center, due to open in 2027.

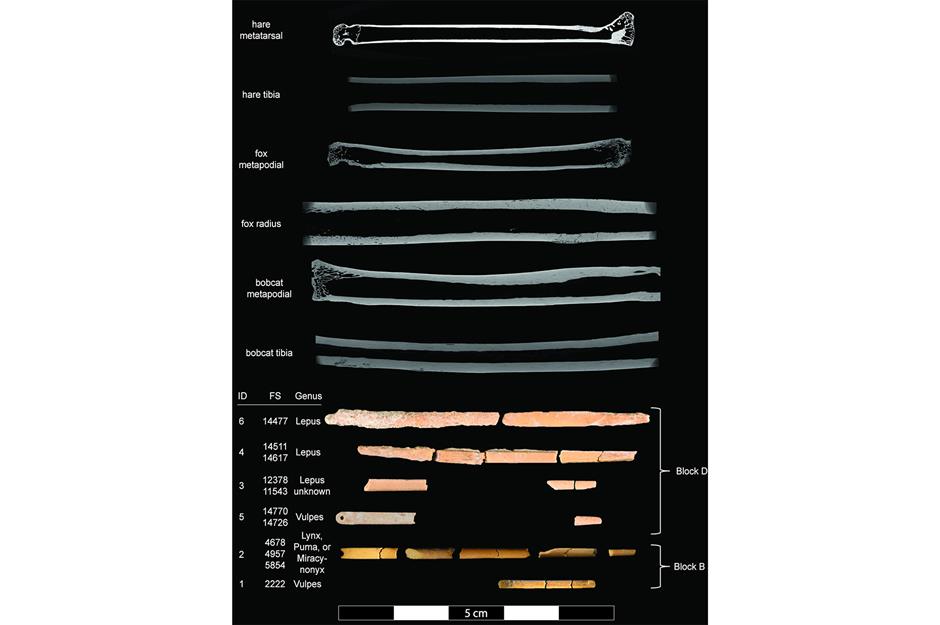

Wyoming: Bone needles

So small that they almost went undetected, a collection of 32 prehistoric needle fragments dating back 13,000 years were unearthed in Wyoming between 2015 and 2022. Analysis has revealed that they were made from the limbs and paw bones of small mammals such as red foxes, bobcats, hares, rabbits, and the now extinct American cheetah.

The discovery of the needles, now held at the University of Wyoming, provides strong evidence of the earliest tailored garment production. These garments, warmer and more robust than simple draped fabrics, enabled modern humans to travel to northern latitudes and eventually colonize the Americas.

Now see how we've ranked the world's most exciting archaeological discoveries

Comments

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature