Antarctica: the battle to own the world’s forgotten continent

A sought-after landmass

In 2023, Antarctica isn’t exactly the pristine wilderness you might imagine. The coldest, driest and windiest place on Earth – untouched by humans until around 200 years ago – now contains more than 70 permanent research stations and was visited by over 100,000 tourists in the 2022/2023 season.

At a time when many are questioning whether the end of the Antarctic Treaty in 2048 could lead to mineral, oil and gas exploitation in the region, read on as we chart the continent’s fraught history from early exploration to the present day. All dollar amounts in US dollars.

The first sighting

On board his ship Resolution in 1773, Captain James Cook (pictured) is thought to have become the first person to knowingly cross the Antarctic Circle. The first sighting of the continent wouldn’t be until nearly 50 years later.

The first person to lay eyes on the continent is debated, but we do know that English mariner William Smith spotted Livingston Island, part of the South Shetland archipelago in Western Antarctica, in 1819. Two years later, the first landing on the Antarctic mainland was thought to have been made by American captain and seal fur trader John Davis.

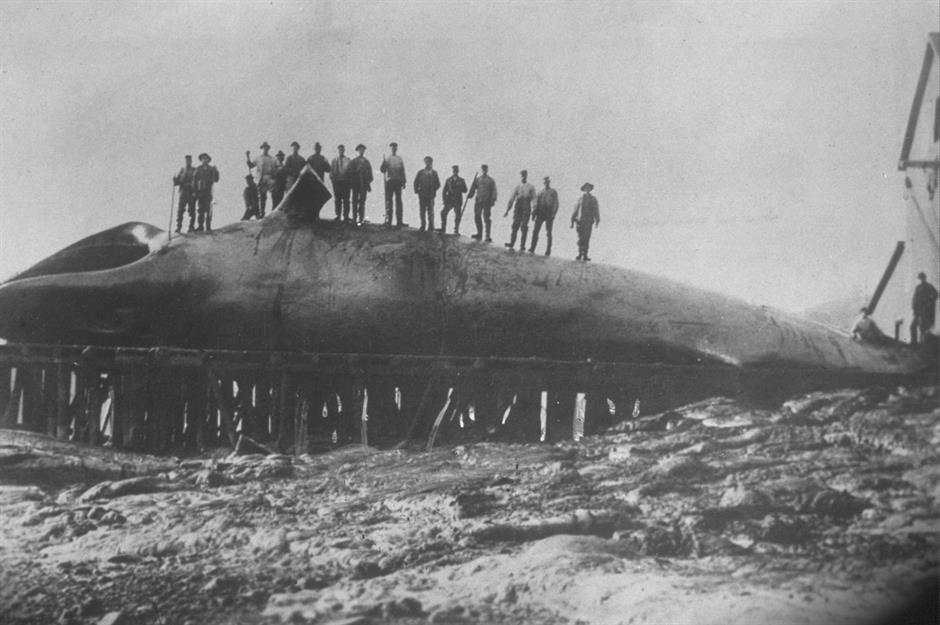

Whaling wars

In the early 1900s, whaling became extremely lucrative, as the animals were prized for their oil and meat. Initially, Norwegian and British whalers made up the bulk of the industry. In 1908, the British made a territorial claim on the Antarctic with the intention of taxing whalers from other countries. Later, in 1939, a German expedition arrived to take over Norwegian territory, establishing a whaling station so it could stop relying on Norwegian whale oil.

Chile and Argentina started to make claims on "British" land, which led Britain to launch a secret mission, Operation Tabarin, in 1943 to strengthen its position on the territory. Conflicts were put to bed in 1986 when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned large-scale whaling in the Antarctic Ocean.

Age of exploration

In the summer of 1910, two expeditions set out to be the first to reach the South Pole. The first, led by British explorer Robert Falcon Scott, set sail in June, while rival Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen headed off in August. Both explorers travelled for over a year, battling incredibly harsh conditions, before Amundsen planted a Norwegian flag on the world’s southernmost point on 14 December 1911.

This signalled the beginning of a scramble for territory, with seven countries making claims on Antarctic land between 1908 and 1942, several of which overlapped.

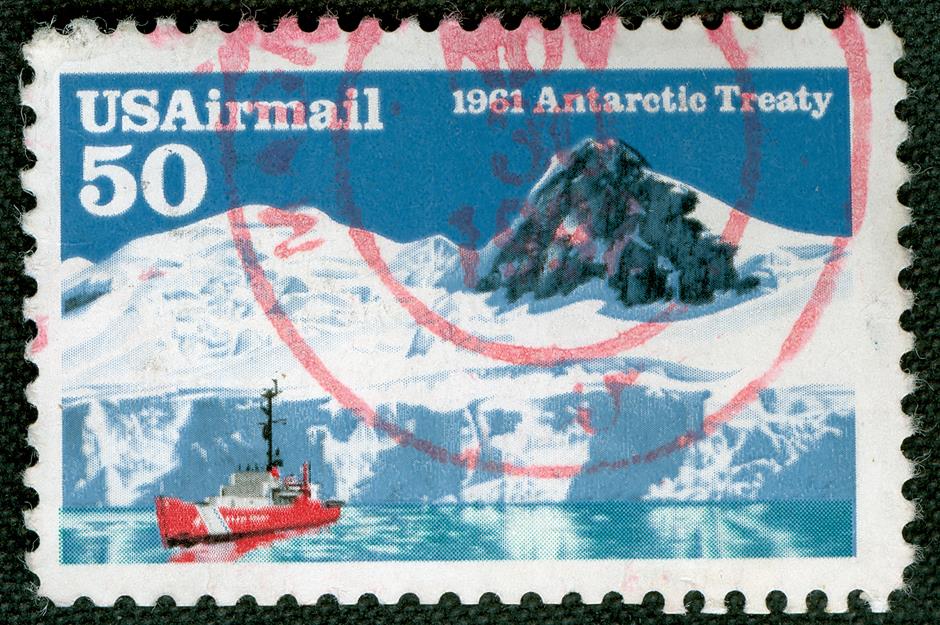

The Antarctic Treaty's moment of peace

In the post-war context of the 1950s, settling disputes over territory and ensuring peace was essential. Following the opening of the continent’s first research station in 1956, an international research programme was established. The Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959 by twelve nations: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the UK, the US, and the USSR.

The Treaty stated there could be no military activity and that the continent would be used for scientific research and cooperation between members. It came into force in 1961.

Commercial fishing

But the waters around Antarctica weren’t part of the Treaty. During the 1970s, large-scale fishing began to take place, with the USSR and Japan fighting for the biggest catches. Krill was one of the most targeted species and catches peaked at more than 500,000 tonnes between 1981 and 1982, most of which was caught by these two countries.

In 1980, the Commission for Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was set up, and from 1982 it enforced bans or limits on most types of fishing. Norway, Korea, China, and Chile are currently the biggest krill fishing nations.

Licence to krill

Krill may be tiny crustaceans, but they represent a mighty global trade. Demand for the creatures, which are becoming popular as part of health food supplements, has doubled over the last two decades.

In 2018, following pressure from environmental groups and support from fishing companies, a proposal was brought forward to create an Antarctic ocean sanctuary, which would have protected almost 700,000 square miles of ocean. The legislation was blocked by China, Russia, and Norway when brought to the Antarctic Ocean Commission in November of that year.

A rare delicacy

Antarctic toothfish, which can reach up to six feet (1.8m) in length, are a vital part of the food chain. However, they’re threatened by illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing in the waters around Antarctica.

In January 2015, fishermen were caught hauling in an illegal Antarctic toothfish catch on board a ship estimated to be carrying $1 million worth of the stuff. There's a lucrative trade in selling it to North America labelled as Chilean sea bass. Pictured is a New Zealand patrol boat on the lookout for poachers near Antarctica.

Whaling

It’s not just fish being poached – despite a ban on large-scale whale fishing back in the 1980s, whales are also under threat. In September 2018, the WWF reported that Japanese whalers had killed more than 50 minke whales within the protected Antarctic region. They had exploited a legal loophole, which allows the hunting of whales for “scientific” reasons, but it means their lucrative meat still goes on sale.

Business Insider reported earlier this year that a Japanese whaling company was planning to open whale meat vending machines across the country to fuel demand for products including whale sashimi, whale skin, whale steak, and whale bacon.

Early discussion of mining

There are known deposits of oil and other minerals in Antarctica. According to estimates by the US Geological Survey, the continent may be home to 160 billion barrels of oil and 30% of the planet's undiscovered natural gas.

Discussions about resource exploitation began in 1970 when the UK and New Zealand raised the issue. Between 1982 and 1988, the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Resource Activities (CRAMRA) was established with the intention of setting out environmental protections for potential mining activities that could take place.

Environmental concerns

The Convention was short-lived. While 33 nations signed it, France and Australia refused, saying that mining should be forbidden entirely on the continent.

Following meetings that took place between 1989 and 1991, CRAMRA was overturned. In its place, a new Protocol on Environmental Protection entered into force, stating: “Any activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research, shall be prohibited.”

Mineral resources

It’s not just oil and gas that could be lurking beneath the icy surface. According to the CIA World Factbook, “chromium, copper, gold, nickel, platinum and other minerals, and coal and hydrocarbons have been found in small noncommercial quantities”.

Millions of years ago, during the Mesozoic times, Antarctica was part of a giant continent called Gondwanaland, which included America, South Africa, and Australia. Close similarities have been observed between the geology of these mineral-rich regions and Antarctica, which could mean a wealth of minerals exists there.

Expanding research

China is currently building its fifth research station in Antarctica – despite the fact it’s yet to receive environmental approval – and reportedly has plans to become a "polar powerhouse" by 2030. The nation has also been seeking to set up a “specially managed area” (ASMA) around its remote base at Dome A, which some commentators view as a way to increase its influence in the region.

The country is also investing heavily in infrastructure and capability in Antarctica, including investment in its global GPS network BeiDou, which will aid the Chinese military.

Military involvement

The Antarctic Treaty states that countries should have no military involvement in the continent – a rule that some members have flouted. It's known that Chile and Argentina have an army presence on the Antarctic mainland, while other countries may have unreported military or civilian security officers acting as a stand-in for military presence.

Meanwhile, the use of China’s base for GPS, which will benefit its armed forces, has also posed questions about whether it has undue influence in the area.

Cruising ahead with tourism

Climate change has spurred interest in Antarctica, as tourists want to visit before the ice diminishes. With more than 100,000 tourists visiting last season and trips costing from $10,000 (£7.9k) to upwards of $100,000 (£79k), there’s big money to be made.

But not everyone is playing by the rules. Stats presented at a recent annual Antarctic Treaty meeting revealed that 45 private yachts were spotted in sensitive Antarctic waters, nine of which had visited without permission.

Precious water resources

As global temperatures rise, freshwater is in high demand. Could the Antarctic ice sheet, which currently holds 60% of the world’s fresh water, solve global supply issues? One firm in the UAE seems to think so. The company, headed by businessman Abdula Alshehi, plans to tow icebergs five thousand miles from the Antarctic sea to its Fujairah coast to harvest water from them.

According to Nature, an iceberg big enough to withstand the journey to the UAE would need to be at least 4,101 feet (1,250m) long and 1,968 feet (600m) thick. But those dimensions pale in comparison to the world's largest iceberg, which hit headlines this year...

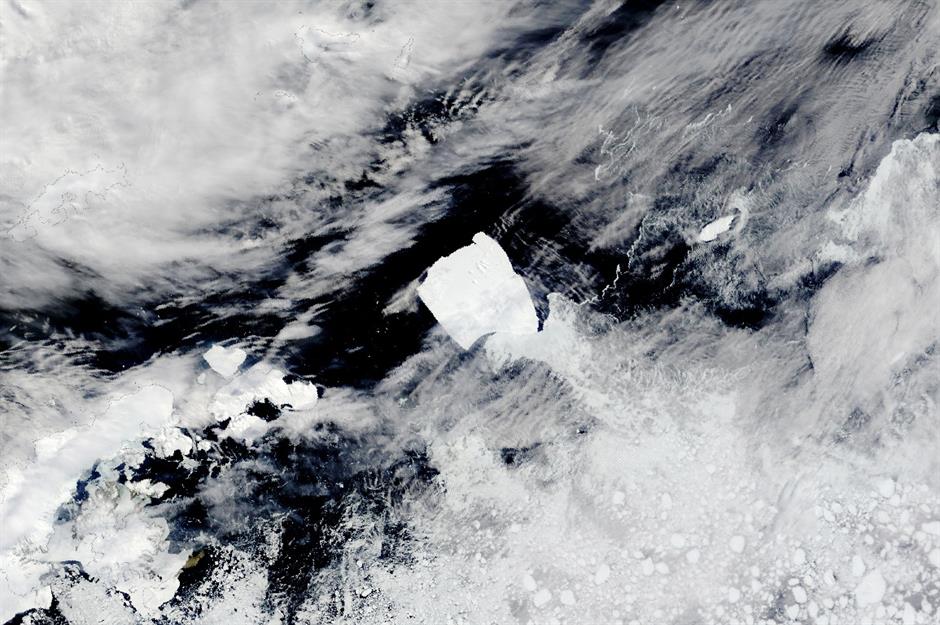

Iceberg on the move

Dubbed A23a (pictured), the largest iceberg in the world is reportedly on the move. The berg split off from the Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986 and has been lodged on the seafloor ever since. But in 2020, A23a began to become unstuck as its underside melted from below – a natural process for icebergs stuck on the seafloor, which, according to the BBC, is unlikely to be a direct result of climate change.

It's believed ocean currents will carry the mammoth berg, which is a staggering three times the size of New York City, to a body of water known as the "iceberg graveyard". From there, however, its vast size could mean it survives as far as South Africa, posing a potential problem for major shipping routes. Watch this space...

Potential mining opportunities

Although there's currently a ban on mining in Antarctica, it comes up for review in 2048. That may seem a long way off, but some countries, including China and Russia, have already expressed interest in overturning it.

Experts have begun to speculate what might happen in 2048. Ann-Marie Brady, editor of The Polar Journal, told ABC News, “Countries participate in Antarctic Treaty governance but you can see in many instances backup plans and contingency plans that countries are engaging in.”

The future of the Treaty

When the Antarctic Treaty comes under review in 25 years, the future of the world’s forgotten continent will be at stake. As climate change puts pressure on resources, global focus is likely to intensify on everything from Antarctica’s marine life to minerals. Yet some believe the most significant challenges will become before the Treaty ends, as different parties grapple with conflicting environmental and economic interests.

"Largest" aircraft ever to land in Antarctica

In the meantime, countries have been scrambling to break records in the continent. In November, Norse Atlantic Airlines marked "a groundbreaking milestone in aviation history with the first landing of its Boeing 787 Dreamliner... at Troll Airfield in Antarctica." According to various media sources, the plane is the largest aircraft ever to land in Antarctica, though Forbes has said this "doesn't hold water" and Norse Atlantic Airlines didn't make the claim itself.

But size isn't everything. The aircraft was certainly the first model of its kind to touch down in Antarctica, and it carried 12 tonnes of research equipment destined for the Norweigan Polar Institute.

Now discover which countries are using the most renewable energy today

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature

Most Popular

Destinations Incredible recent discoveries from ancient Egypt